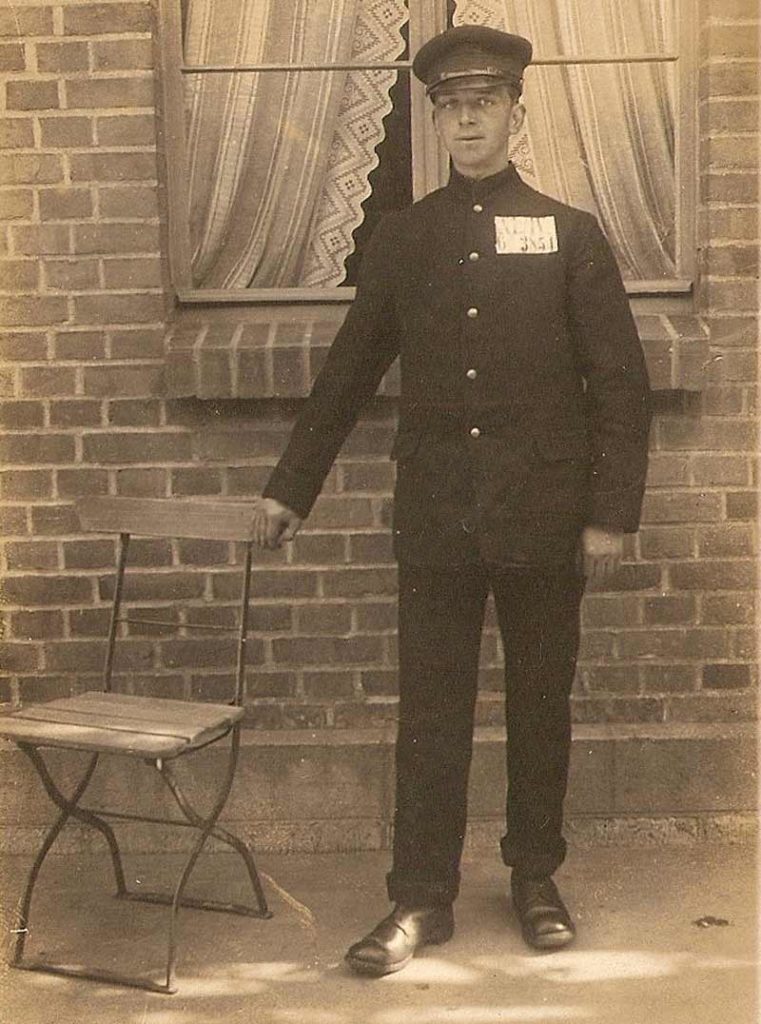

Private James Johnstone signed up in 1914 and was wounded twice during his front-line service with the 5th Battalion (Scottish Rifles). [Courtesy of Fiona Jackson/Family Archive]

Those were the orders given to Private James Arthur Heysham Johnstone of the 5th Battalion (Scottish Rifles)—known as the Cameronians—near Mametz Wood on the night of July 19-20, 1916. It was less than three weeks into the 141-day Somme offensive and the losses had already been staggering.

Johnstone’s 19th Brigade, along with the 33rd Division of the British Expeditionary Force, was tasked to take a forested high ground occupied by the enemy about 3.5 kilometres behind Mametz Wood “at all costs.” The wood itself had been won by the 38th (Welsh) Division the week before, at a cost of about 4,000 casualties.

As it turned out, the enemy was rather hard to miss.

“I was detailed along with 15 other scouts and issued wire cutters,” wrote Johnstone, a 21-year-old postmaster’s son from Gretna Springfield, Scotland. He had worked for a Canadian Pacific Steamship Company-owned shipping firm in Glasgow before joining the army.

“Our duty was to cut the barbed wire entanglements in front of our trenches and the German trenches so that our Battalion could get through. Also to keep a sharp lookout for the enemy.”

As it turned out, the enemy was rather hard to miss. Ensconced in the High Wood, as it was called, they begin shelling virtually as soon as the scouts began to move.

“The scout sections left Mametz Wood about 9 p.m. on the 19th, and we went along a road under a terrific bombardment from the Germans,” he wrote. “We eventually got to a trench occupied by the remnants of a Manchester Battalion.

“We were working in twos and started out on the wire-cutting and the sergeant in charge of our party told us that our Battalion would be up about midnight. Having completed the cutting of the wire under a murderous shell fire, we returned to the trench and awaited the arrival of the Battalion shortly after midnight.

“About 1 a.m. we began advancing some 800 yards during which period the Germans were shelling all the time. Jack Johnsons, coal boxes, whizz bangs etc. were sent over.”

The British guns, along with a battery of French 75mm guns, opened up at 2:30 a.m., firing some 2,000 shells into the wood in front of the Scots. When the shelling stopped, the British forces resumed their advance, only to find that the Germans had withdrawn.

Or so they thought.

It was still dark and misty, and visibility was poor. The British soldiers moved forward, tossing grenades into every dugout they encountered along the way. By 4 a.m., the first traces of the dawn light were beginning to illuminate the area. The mist still hung heavy but the Scots could see moving figures about 100 metres ahead.

Officers expected a counterattack. The Tommies dug in and commenced “rapid-fire.”

“And then the fun began,” wrote Johnstone. “It was exceedingly hot; what with the German machine gun and rifle fire from all directions we were kept busy.

And so Johnstone tried, running with other wounded from shell hole to shell hole.

“About 6 a.m. I got wounded by a bullet in the arm and side which counted me out of action. My side bled a good deal and I began to feel faint and sick when my chum Edward Cowie—a Glasgow lad—bandaged my wounds for me and gave me a drink of water as I had acquired a great thirst.

“He gave me a cigarette and told me to try and manage back to our dressing station.”

And so Johnstone tried, running with other wounded from shell hole to shell hole “through a tremendous hail of bullets” from elevated machine-gun nests in surrounding trees.

“The Germans outnumbered us considerably and seemed to be flanking us on both sides as well as coming up in the rear,” Johnstone wrote. “We then had machine guns playing on us from all directions.

“My puttees and trousers were badly torn with barbed wire and I had also sustained a deep gash from barbed wire on my left knee from which blood was oozing out.”

By this point, they had reached a crater to the side of a sunken road running through a wood. They waited for reinforcements, but none came.

“There were several wounded on this road and the dead and dying lay strewn all over the place. The scene was one not to be forgotten. [It] presented an awful spectacle, what with the groans of wounded and dying men, and the branches breaking off trees, as well as trees falling which had been uprooted with the artillery.

“I saw several kilties lying dead as well as plenty of Germans, and the smell from the dead owing to the excessive heat during the day was awful.”

Johnstone and nine or 10 others were taken prisoner about 8 a.m.—after the Germans considered whether to capture them or simply kill them, a relatively common practice at the Somme. Mercy prevailed. Two Germans took the wounded back to a dressing station through “a terrific British bombardment.”

“It was on my way back to the dressing station that I noticed my chum Edward Cowie, who had bandaged me up with my field dressing, lying dead having apparently been shot through the head.”

The dead “kilties,” he later learned, were Glasgow Highlanders who had been trapped in the same manner on July 15 after the Germans had tunneled beneath and behind them, “getting up at our backs.”

German medics patched up some 30 PoWs; two uhlans—light cavalrymen armed with lances—led them out of the field dressing station on a 13-hour march over 40 kilometres to a German field hospital in an occupied French village.

“During our march to this place the French civilian population would attempt to throw pieces of bread to us, but their hospitality to British prisoners was not allowed by these two pigs of German culture, who would chase the civilians right up to their doors.

“It was only their quickness in shutting the door that saved these poor civilians from getting an unmerciful blow from the Huns lance which was freely used.”

Once at the hospital, the prisoners were each given a piece of black bread and “coffee” made from burnt grain. The bread was very welcome, he said, since they’d had nothing to eat since 5 p.m. the day before at Mametz Wood.

They were given some straw outside a hospital tent filled with wounded Germans. Exhausted, they slept soundly until they were roused at 6 a.m. and loaded aboard a train. Belongings in hand and cart, columns of refugees were leaving the village by road as the train departed. The British guns were within range.

“A Hun on the train who spoke a little English gave us some encouragement by informing us that we would get a lot of sympathy, and meet a lot of kind friends in Germany,” he wrote. “Also that we had come over here to kill the German people and it would have been better if we had remained at home and played croquet.”

They were imprisoned there for two years until the war ended.

About two stations up the line, they were moved from a Red Cross carriage to a cattle truck at the rear of the train, where they were packed in with more than 30 French prisoners and some sentries “just like sardines in a tin.”

It was July 21 and by 2 p.m. they had reached their destination, Saint-Quentin, where the PoWs were transported to a church-turned-hospital. There, they slept on scattered straw “infested to its fullest with vermin.”

The following morning they boarded a train for Stalag Soltau, a prisoner-of-war camp in Germany. They were imprisoned there for two years until the war ended, with more than 7,000 Cameronians among the dead.

A postcard picture of Private James Johnstone in his PoW uniform. He managed to send his parents several of the postcards over his two years in captivity. [Courtesy of Fiona Jackson/Family Archive]

“It is not possible to get any more definite news meanwhile,” he wrote. “Indeed you will hear at home before we do. There are very many in the ‘missing’ list with your brother—brave laddies all of them. It is some consolation to know that the 5th did so well, and gained their objective. But for you all at home it is a time of great suspense and anxiety and I pray that you will be upheld and kept.”

He signed off “with sincere sympathy,” the name “White” the only legible part of his signature. Johnstone’s parents, Robert and Rachel Johnstone, received official confirmation via form letter that their son was missing.

“Should he subsequently rejoin, or any other information be received concerning him, such information will be at once communicated to you.”

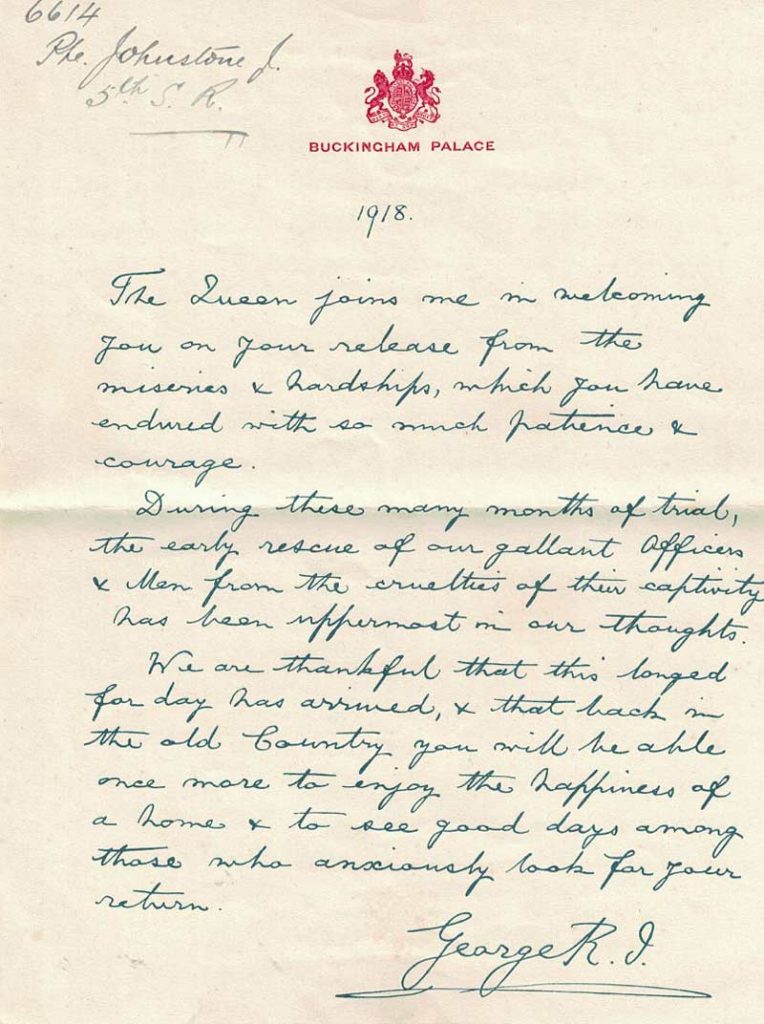

They eventually did learn his fate. Johnstone sent several PoW postcards with his image on them home to his parents over the course of his captivity. After he was repatriated, he received a handwritten welcome home from King George V and went to work at the Ministry of Labour, where he rose to the position of manager. He married Jane Jackson in 1922. The couple lived in Gretna and had three sons and a daughter. The two eldest boys served in the Second World War.

Johnstone received a handwritten welcome home from King George V upon his arrival back in Scotland. [Courtesy of Fiona Jackson/Family Archive]

James Johnstone died in 1973, age 78. His granddaughter, Fiona Jackson of Melrose, Scotland, dove into the family archive and provided much of the material for this column.

—

Canada and the Brutal Battles of the Somme, the latest in the Canada’s Ultimate Story series, is on newsstands now. You can also order it for delivery to your home from the Canada’s Ultimate Story website.

Advertisement