Pierre Berton called him one of the toughest war correspondents he ever knew, a trusted and familiar newsman who “ate censors for breakfast.”

In 2020, an Ontario firm auctioned off the estate of Gerard William Ramaut (Bill) Boss, 13 years after he died of pneumonia in an Ottawa hospital, age 90. The collection of art, books, photographs, newspaper clippings, letters, telegrams, mementoes and press credentials showed the man known affectionately by his wire-service initials “bb” to generations of Canadian Press reporters and editors for what he was—an eclectic, highly cultured, much-travelled and multi-talented writer, raconteur and Renaissance man of the highest order.

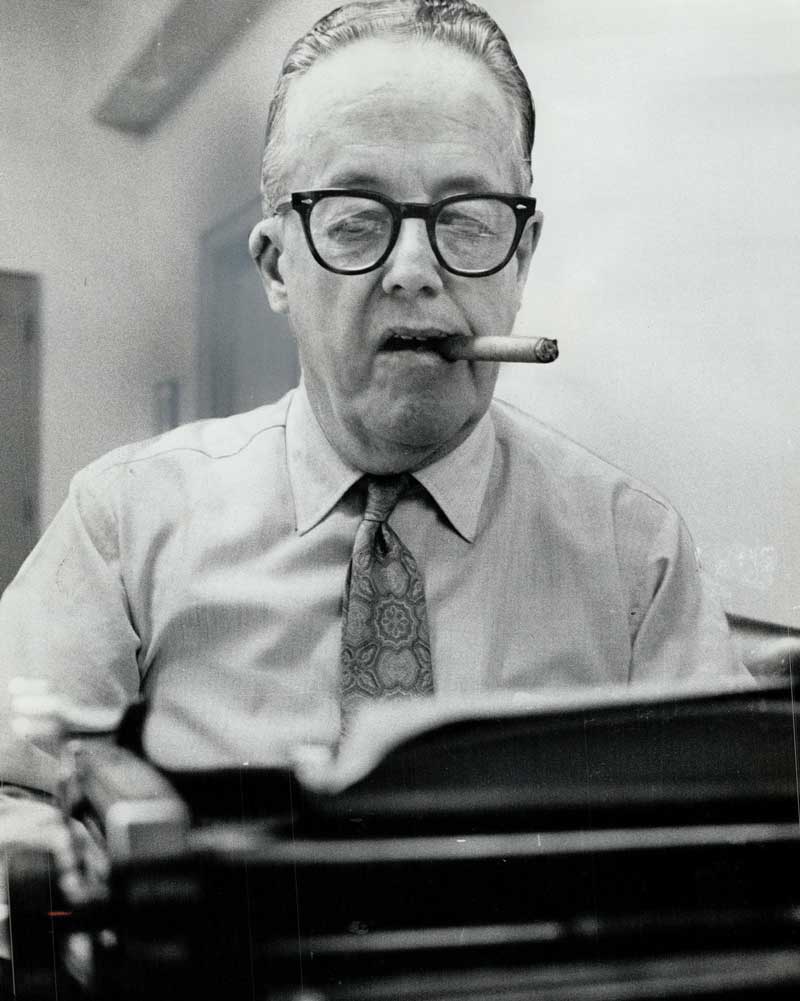

Born May 3, 1917, in Kingston, Ont., Bill Boss was the epitome of foreign correspondents—“a man with a mission,” one of many articles about him said—who roved the world’s hot spots in goatee, khakis, silk scarf and black beret.

“The Bill Boss byline has always been a trusted and familiar one to Canadian newspaper readers,” Berton wrote in the Toronto Star in 1958.

“I got to know him in Korea, and he was the toughest reporter I encountered there. He wasn’t only tough physically, he was tough in other ways. He was as fiery as his red beard.”

Boss’s career with the national news service was a relatively brief 14 years, but the legacy he left behind as one of the wire service’s legendary war correspondents endured until he died.

“I got to know him in Korea, and he was the toughest reporter I encountered there.”

He was among the elite of Second World War reporters, ranking alongside the likes of Ross Munro and Bill Stewart of The Canadian Press, Matthew Halton and Peter Stursberg of CBC and Charles Lynch of Reuters.

“Bill Boss is the last of the generation of Canadian Press correspondents from the Second World War who did a remarkable job of reporting from the battlefields of Europe and the Pacific,” said Scott White, the Toronto-based editor-in-chief of The Canadian Press at the time that Boss died in October 2007.

“Boss built his own legend in Korea, where he was seen as the senior Canadian correspondent during the entire conflict. The stories about him at Canadian Press are truly the stuff of legends—even 60 years after the fact.”

Boss was more than a journalist. A member of the Canadian News Hall of Fame with degrees in arts and philosophy, he spoke French, Italian, German, Dutch and Russian, along with a little Korean and Japanese, as well as his native English.

He played piano and organ, arranged and composed music, and conducted symphony orchestras in Canada, Italy and the Netherlands.

As a journalist, he worked for the Ottawa Citizen and The Times in London before serving a stint with the Canadian army in Italy as a public relations officer, often escorting journalists to the front.

After two years, Lieutenant Boss was “drafted” out of the army by Canadian Press chief Gil Purcell to report as a civilian on the Allied advance through Italy and Northwest Europe. How Purcell, a former war correspondent who was known to wield great influence in high places, managed to convince military authorities to let Boss go, remains a mystery. But Boss seized the opportunity.

“It was a terrific break for me,” he recalled years later. “As soon as the appointment was made official and I was free of army red tape, I grew a beard.

“My feeling was that brass hats might be interviewed by umpteen correspondents and never remember one of them. But they couldn’t forget a man with a red beard.”

And they didn’t.

Berton said some military public relations officers lived in terror of Boss.

“He fought like a tiger to get his copy out, and to report things as he saw them,” wrote Berton. “Some high-ranking officers hated him and, on occasion, tried to have him thrown out of Korea because he wrote certain unpalatable things about the army there.

“But Boss wouldn’t be budged. He holds the Korean endurance record for war correspondents.”

Indeed, the intrepid bb covered every major Canadian battle of the three-year war, acting not only as a front-line reporter, but what yet another story about him described as an “unofficial entertainment officer, rumour-spiker, father confessor, shopping-service director and messing officer.”

His authoritative reporting from Korea broke the mould. Boss didn’t rely on formal briefings from the brass and their spokesmen for his stories; he got the lowdown directly, with his own eyes and ears and from the troops who did the fighting—a testament to the trust and respect the soldiers had for him, his commitment and his reporting.

“Canadians fought until their ammunition was exhausted, then hurled their rifles with bayonets attached like spears into the attacking Chinese when the 2nd Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry stopped the latest Chinese offensive cold in its tracks in Korea’s west central sector,” he wrote after the monumental Battle of Kapyong, where some 1,500 troops, largely Canadian and Australian, turned back 10,000-20,000 Chinese in April 1951.

The story, placelined “With the Canadians in Korea,” included graphic descriptions of the fighting by the Patricias themselves, including how the enemy’s rubber shoes allowed them to move “quiet as mice” until they were right on top of the Canadian trenches.

“He fought like a tiger to get his copy out, and to report things as he saw them.”

“They would keep on coming in waves,” a sleepy, grimy and unshaven Sergeant Roy Ulmer of Castor, Alta., told Boss. “There’s a whistle, they get up with a shout about ten feet from our positions and come in.

“The first wave throws its grenades, fires its weapons and goes to ground. It is followed by a second which does the same, and a third comes up. Where they disappear to, I don’t know. But they just keep on coming.”

Later, about the time of the fighting around the hill known as Little Gibraltar, a Patricias sergeant would admit to him how the Chinese artillery barrages and banzai-style attacks were unnerving to his fresh troops.

“The Communists are using much more artillery now and sometimes it gets hard to just sit and take it,” he said. “My fellows are good, fairly new, and sometimes they get jittery during the shelling, and if the Chinese come in and attack, they get excited during the grenade throwing.”

Boss’s estate sale was peppered with pictures from the 1950-53 conflict, where he earned the 1951 National Newspaper Award (NNA) for feature writing with a story recounting the travails of a Canadian soldier from the time he was wounded to his repatriation to Canada.

Two years later, Boss was awarded a second NNA, this time for what was then called “staff corresponding,” (overseas reporting) with a series of stories from Moscow.

But one of Boss’s greatest coups is not recognized by any award or official record. He’d just landed in Pusan, Korea, with the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry—the first Canadians in—and the resilient, ever-resourceful Boss wanted to shake his reliance on military authorities to get where he wanted to go. To do so, he needed transportation.

So, Boss went to the quartermaster and said he needed Scotch enough for “the CP,” never exactly specifying that it was The Canadian Press, not the command post, that wanted the alcohol.

The quartermaster provided him with Scotch enough for an entire company, or about 120 men. Boss took the Scotch and traded it for a tent, a generator, a trailer and a jeep, which went down in the annals of wire-service lore as “The CP Jeep.” He subsequently established what was arguably the war’s first press office.

One well-known picture in the auction sale showed him and a young Korean hoarding cans of food on the jeep’s hood, with “The Canadian Press” declaring his status on a banner below the windshield.

“Each of the correspondents had their own style of reporting and writing,” White said. “Bill did both with drama and flair—a characteristic he kept right until the end.”

In his later years, bb served as an adviser to White on the wire service’s coverage in Afghanistan, where it maintained correspondents throughout the entire war.

“He had a healthy mistrust for authority when it came to the reporter-military relationship,” Scott said at the time, “and that wisdom still applies today.”

Between wars and after, Boss reported from all over Europe, Africa and Asia. He worked in all the wire service’s North American bureaus, from Vancouver to New York, where he played organ in St. Patrick’s Cathedral.

A self-professed lifelong bachelor, Boss eventually left The Canadian Press to become a public relations man—a shameful sellout, according to Berton.

One of his last stories was written for Veterans Affairs Canada during a 2004 reunion tour of Canadian battlefields and war cemeteries in Italy, many of them bearing uncanny resemblance to the mountainous Korean peninsula.

“They had climbed and fought in the very sight of the Germans higher up the mountains hereabouts, who were determinedly, but unavailingly, trying to oppose their advance,” he wrote from the mountain-top graveyard at Agira in Sicily, where 490 Canadian soldiers are buried.

“It seems so appropriate that this beautifully-kept cemetery should be way up there at an altitude akin to that at which their lives were seized.”

Advertisement