A captured U-190 floats in St. John’s Harbour, Nfld., in June 1945. [Edward W. Dinsmore/DND/LAC/PA-145584]

Nestled away on the top two floors of a four-storey stone-and-brick building overlooking the St. John’s waterfront, just a few metres from the Newfoundland National War Memorial, is a piece of Second World War history unlike any other.

Fifty-nine precarious steps up the back of the former warehouse, the Seagoing Officers’ Club, established by Captain Rollo Mainguy—a B.C. native commanding Canadian navy destroyers in the British colony of Newfoundland—is the stuff of legend.

A retreat and a respite for Allied naval and merchant marine officers between sailings on the North Atlantic run, it became forever known as the Crow’s Nest after a Canadian army colonel, gasping from his upward trek, mopped his beaded brow and uttered the immortal words: “Crikey, this is a snug little crow’s nest.”

Opened in January 1942, the warm-wooded refuge with its planked floors and beamed ceilings became home to a growing number of crests, etchings and artifacts deposited by its clientele on behalf of their ships.

Captain Rollo Mainguy in the Seagoing Officers’ Club in September 1942.[Gerald M. Moses/DND/LAC/PA-204634]

On virtually every vertical surface emerged a unique gallery of the Battle of the Atlantic, a time when Newfoundland had, for all intents and purposes, become the “Gibraltar of America” that its former prime minister, Robert Bond, predicted it would be.

War was transforming the world—including this grand island affectionately known as The Rock.

“Perhaps nowhere…was there a garret exactly like the Crow’s Nest,” wrote Joseph Schull in his 1950 book Far Distant Ships. “Reminiscences went round the world, and doubtless still are on the wing, of the loud and smoky room where ships’ crests and bells and trophies hung thick on the wall and where women were allowed on Tuesday nights only, provided they do not clutter up the bar.”

The club is still there, now a refurbished Canadian national historic site, a living testament to the ships and men who fought the war’s longest battle and, by their presence alone, acted as catalysts helping usher the island into the modern world.

Among the Crow’s Nest artifacts is the periscope from U-190 (see “Artifacts,” page 94), one of the last German subs to surrender, on May 11, 1945—three days after VE-Day. Canadian warships brought the boat into St. John’s before it was moved, examined and scuttled off Halifax—but not until the periscope was salvaged and eventually brought back to the port where, for many, the war began, and ended.

Poking out of the building’s roof, the signature element of the U-boat war now provides, not the silhouette of another victim, but a sweeping view of downtown St. John’s and a sheltered, tranquil harbour populated by fishing trawlers, oil service vessels and coast guard ships—all of it very different from what came before.

For those fortunate enough to be granted passage through its door, the Crow’s Nest is an intimate history of an era of great turmoil and transformation. But the living legacy of WW II in Newfoundland can be found in virtually every corner of the province where the wartime forces of Canada and the United States, in very tangible and lasting ways, changed the course of the former colony’s history.

The Jan. 24, 1934, telegram from a magistrate in the outport of Burgeo, Nfld., to the justice minister on the other side of the island amounted to a desperate cry for help.

“ABOUT FORTY MEN [CAME] TO ME IN STARVING CONDITION,” it said. “I CONSULTED RELIEVING OFFICER WHO INFORMS ME NOTHING CAN BE DONE THEIR ALLOWANCE WILL NOT BE DUE TILL EIGHTH AND NINTH FEBRUARY STOP IMPOSSIBLE THESE FAMILIES EXIST FOURTEEN DAYS WITHOUT FOOD STOP CAN ANY ARRANGEMENTS BE MADE HELP OUT SITUATION IF NOTHING I FEAR CONSEQUENCES.”

There were few phones. It would be another 31 years before the broad, U-shaped arc of the Trans-Canada Highway would connect Port aux Basques on the island’s southwest corner to St. John’s, 900 kilometres away in the southeast.

Government documents in Ottawa were describing Newfoundland as Canada’s “first line of defence” and “the key to the western defence system.”

Dozens of planes, mostly bombers, line the Tarmac at the Royal Canadian Air Force base in Gander, Nfld., in 1944.[U.S. Air Force/090223-F-0304D-003]

Remote, weatherbeaten and chained to the make-and-break of a fickle fishery controlled by a handful of merchants in St. John’s, Depression-era Newfoundland was a Dickensian nightmare, and worse, for a disproportionate number of its 289,000 residents.

“Newfoundland was hit very hard by the Great Depression,” Carmelita McGrath wrote in Desperate Measures: The Great Depression in Newfoundland and Labrador, a 1996 history produced by the province’s writers’ alliance.

“Many people were out of work or had very low wages. Hunger was a real problem…. More and more people were forced to apply for public relief.”

“The dole,” as it was known, didn’t come in the form of cash; it consisted of what were essentially food stamps redeemable at local merchants for specific goods.

“Many people said that you could not live on the dole. Often, people ran out of food before their next ‘relief order’ would allow them to get more. Most people hated the dole. They wanted work. They wanted to choose what they ate.”

McGrath describes how the Depression upset the delicate balance that was survival in Newfoundland at the time: life on the edge.

“On one side of this edge is a certain amount of security,” she explains. “There is enough food, decent housing, heat and comfort. On the other side of the edge there is little security, hunger, poor housing, cold and discomfort.

“During the Great Depression, more and more people were pushed over the edge.”

Largely descendent from British, French, Spanish and Portuguese fishermen, Newfoundlanders are a rugged, passionate people. Eventually, dissatisfaction—indeed, desperation—boiled over. There were demonstrations, riots, even looting.

The government, however, was up to its ears in debt.

Newfoundland had given up its status as a dominion of the British Empire in 1934 to be governed by a six-member commission appointed out of London. Now a colony, it was kept afloat by loans and grants from the British Treasury.

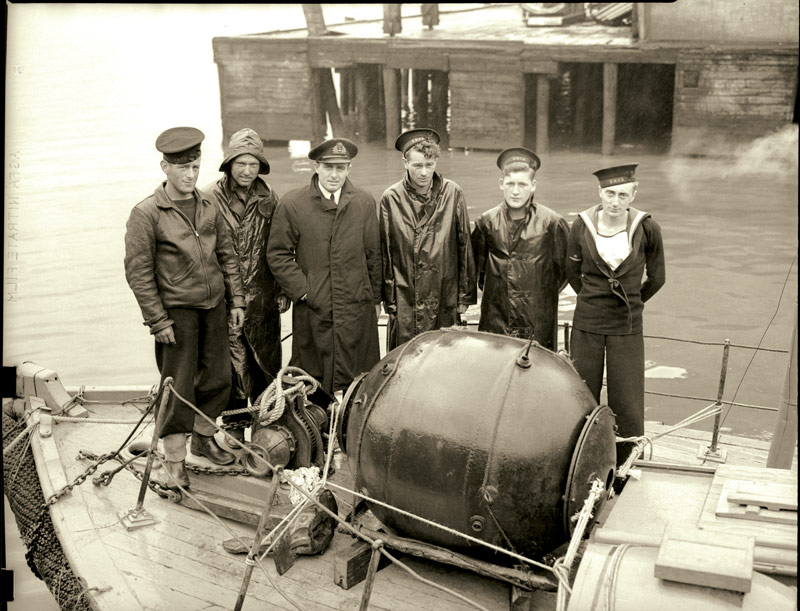

Naval personnel of S.S. Miss Kelvin pose with a recovered mine in St. John’s, Nfld., in July 1942. [DND/LAC/PA-161614]

It all changed in the spring of 1940 when, after defeating virtually all of western Europe, Hitler’s forces stood poised to invade Britain.

On this side of the pond, government documents in Ottawa were describing Newfoundland as Canada’s “first line of defence” and “the key to the western defence system” should the Nazi advance come this far.

As for Newfoundland itself, the colony was all but defenceless. It had virtually no troops, no guns, no fortifications, and the government didn’t have the funds to provide them. Britain was in no position to help.

On Nov. 10, 1940, seven Hudson bombers manufactured in Burbank, Calif., took off from the airport at Gander and headed out into the night across the Atlantic. They were the war’s first transatlantic ferry flights, 13 years after Charles Lindbergh made his famous solo crossing.

The crews disembarked the next morning—Remembrance Day—at Aldergrove, Northern Ireland, wearing poppies. “At a single stroke, Newfoundland had become ‘one of the sally-ports of freedom,’” says a Canadian War Museum history.

Indeed, “in a very short time,” wrote historian Paul W. Collins in a 2015 paper for the provincial government, “Newfoundland boasted five military and civilian aerodromes, two naval bases, two seaplane bases, plus five army bases.”

During the next five years, tens of thousands of Canadian and American military personnel were to be posted throughout the island and Labrador.

“As the Colony’s entire population stood at less than 300,000 and Newfoundland’s capital (and largest) city boasted a mere 40,000 souls,” wrote Collins, “this ‘friendly invasion’ held tremendous economic, social, and political repercussions for Newfoundland—many still felt today.”

“This infusion of cash into the Newfoundland economy had a huge impact on the people of Newfoundland both directly and indirectly.”

Overlooked as a “liability” when Confederation was struck in 1867 (Newfoundlanders didn’t want Canada, either), the island was now regarded as an “essential Canadian interest” and an important part of the “Canadian orbit.” Prime Minister Mackenzie King argued in September 1939 that not only was the defence of Newfoundland “essential to the security of Canada,” but guaranteeing the colony’s integrity would actually assist Britain’s war effort.

Ottawa, however, did not act until Nazi Germany overran France and British soldiers were driven off the beaches of Dunkirk, at which point it dispatched a battalion of The Black Watch of Canada to protect Newfoundland’s Botwood seaplane base and the airfield at Gander, where it also stationed five Douglas Digby bombers and crews from 10 Squadron, Royal Canadian Air Force.

Shortly after, Canadian contractors started building Camp Lester on the outskirts of St. John’s. Brigadier Philip Earnshaw, the newly appointed Commander, Combined Newfoundland and Canadian Military Forces, arrived in November.

By the end of 1940, nearly 800 Canadian soldiers were posted throughout the Newfoundland capital and surrounds, ready to defend against any German attack.

Canadian troops would also protect Lewisporte (considered a likely enemy insertion point), Rigolet and Goose Bay Air Station (the world’s largest airport by 1943). They also operated artillery and radar installations along the coasts of both the island and mainland.

The Royal Canadian Navy arrived in Newfoundland and set up a Naval Examination Service to control shipping entering St. John’s Harbour.

The British were woefully short of destroyers for convoy escort duty after losing significant numbers during the doomed Norwegian Campaign the previous winter, in the evacuation at Dunkirk in May, and at the outset of the Battle of Britain when the Luftwaffe was attacking Channel shipping.

Prime Minister Winston Churchill appealed to U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt in May 1940 for “forty or fifty of [his] older destroyers” to fill the breach until new construction replaced the losses.

Roosevelt was amenable, but the Japanese attack on the American base at Pearl Harbor was still more than 18 months away and the U.S. was officially neutral. A simple transfer would contravene international law and inflame isolationist sentiment in the U.S.

As a solution, Churchill proposed that Britain, as a gesture of friendship, lease base sites on British territory in the Western Hemisphere to the Americans, and Washington reciprocate with the requested destroyers.

“Unfortunately, such a remedy was a bit too subtle for American policymakers, who preferred a more direct and documented swap,” wrote Collins. “This presented the British with difficulties of their own as a straight exchange of assets could alienate the territories concerned, as well as upset many in the United Kingdom.”

Ultimately, a compromise gave the British their gesture and the Americans their business deal. Leases were given “freely and without consideration” in Newfoundland and Bermuda, while similar facilities were traded in Jamaica, Trinidad, British Guyana, St. Lucia and Antigua for the 50 destroyers.

The United States would go on to develop facilities in Newfoundland at St. John’s (Fort Pepperell/Camp Alexander), Argentia (Argentia Naval-Air Station/Fort McAndrew), Gander, Stephenville (Harmon Air Force Base/Camp Morris) and Goose Bay.

There were also numerous artillery/radar sites granted around the island. By war’s end, tens of thousands of U.S. servicemen were stationed throughout Newfoundland and Labrador, and hundreds of thousands of U.S. military personnel and passengers had passed through the various American facilities throughout the colony.

By the summer of ’42, Collins reports, the Canadians had turned St. John’s into a well-defended harbour and home base for the five corvettes, two minesweepers and four Fairmile patrol boats of the Newfoundland Defence Force.

Personnel pass the time at Royal Canadian Air Force Station Gander, Nfld., circa 1945. [CWM/197660597-013]

It was also home to the Newfoundland Escort Force, renamed the Mid-Ocean Escort Force—about 70 warships protecting the transatlantic convoys ferrying personnel and materiel to the war fronts. It would also include British escorts sailing out of the U.S. naval base at Argentia, on Newfoundland’s south coast.

Two Canadian corvettes, Chambly and Moose Jaw, recorded the force’s first U-boat kill, U-501, off the southeast coast of Greenland in September 1941. It was during this action that the recently commissioned Moose Jaw famously rammed the damaged sub, ending the German’s first and only war patrol (11 of 48 crew died).

Near Torbay, outside St. John’s, the RCAF had begun building an airbase that in postwar years would become the province’s main airport. Canadian military aircraft protected the city, and the iron ore mines on Bell Island, and patrolled convoy routes east of Newfoundland.

The RCAF group headquarters took up residence alongside the navy at the Newfoundland Hotel in St. John’s. RCAF Air Station Torbay opened in October 1941 with two runways; four Hudson bombers arrived from Nova Scotia in November.

Passenger traffic between Canada and Newfoundland and the railway known as the “Newfie Bullet” had become so congested that in February 1942 the Commission of Government approved regular Trans-Canada Airlines service to and from Canada.

The RCAF developed more facilities at Gander and Goose Bay and made use of the island’s two American aerodromes. RCAF personnel also ran an expanding number of radar stations and an early-warning system.

By 1943, some 5,000 Canadian navy personnel were stationed in St. John’s. Thousands more were at the Buckmasters’ Field Naval Barracks just outside the city. Others would eventually be billeted at new facilities in Harbour Grace, Bay Bulls, Botwood, Corner Brook, and Red Bay and Goose Bay in Labrador.

“The most stunning impact of all this military activity was economic,” declared Collins. “During the fall of 1943 (the peak year of construction) over 20,000 Newfoundlanders were employed in building the various facilities.

“Over the course of the war years, the U.S. invested $114,000,000 (USD) on their facilities in Newfoundland, and the Canadians $65,000,000 (CAD). Further, military personnel rose to upwards of 29,000 (13,000 US, 16,000 CA) in 1943, all of whom purchased local goods and services.

“This infusion of cash into the Newfoundland economy had a huge impact on the people of Newfoundland both directly and indirectly.”

In 1939, Collins continued, nearly 50,000 Newfoundlanders received some form of government assistance; by 1942, for the first time since the Commission of Government was struck in 1934, unemployment was “virtually wiped out.”

Tens of thousands of Newfoundlanders were working on base construction, support and supply. While the Americans tended to supply their bases via direct shipments from the U.S., the Canadians sourced theirs locally.

The cost of living rose dramatically during the war years. Though the Commission of Government tried to implement wage-and-price controls, local employers were still forced to match wages paid by the two occupying forces or lose workers.

“Whereas pre-war, only the merchant, professional and political/bureaucratic elite of the Colony could afford a comparable standard of living to that of the United States and Canada, by 1942, most residents of Newfoundland now tasted the benefits of the booming wartime economy.”

Government revenues, mainly from customs and excise taxes, also rose considerably during the war years. In 1939, the expected deficit was $4 million ($84.6 million in 2025 Canadian dollars). The 1940-41 fiscal year yielded a surplus of $796,531 ($15.3m) on revenues of $16.3 million.

In 1941-42, the commission recorded a $7.2-million surplus (about $131.8 million in 2025 Canadian dollars) on revenues of $23.3 million; in 1942-43 it had a $3.7-million surplus ($66.3M) on revenues of $19.5 million; in 1943-44, it came in with a $6.4-million surplus ($113.9M) on $28.6 million in revenues; and in the final fiscal year of the war, it recorded a $7-million surplus ($123.8M) on revenues of $33.3 million.

By war’s end, the Newfoundland government had a cumulative budgetary surplus of some $29 million (about $512 million in 2025).

Dancers celebrate VE-Day aboard HMCS Burlington in St. John’s, Nfld. [Crow’s Nest Military Artifacts Association]

At 10:30 a.m. on May 8, 1945, the siren atop the Newfoundland Hotel began wailing as it had every Thursday morning since 1939, reminding citizens that they were at war. On this joyous Tuesday, however, it marked the end of the greatest conflict the world had ever seen.

In homes across the city, in coastal outports, and at outposts in Labrador, families, service personnel and others gathered around radios to listen as Aubrey MacDonald of the Broadcasting Corporation of Newfoundland held a microphone out a window of its top-floor studio in the Newfoundland Hotel. The streets of the city were flooded with celebrants.

“You are hearing the rejoicing, the unabated rejoicing of our people in St. John’s which has followed spontaneously the great announcement by Prime Minister, Mr. Winston Churchill, that the war in Europe has ceased in an Allied victory,” he said.

“Listen to the whistles, the steamers, the church bells, as our people greet them in great jubilation. The town is bedecked with bunting. Flags are flying. And just now, our people are releasing the pent-up emotions in a torrent of joyous emotion.

“The war in Europe is over!”

And so, too, to a large degree, were the days of Newfoundland’s failing economy and starving populace.

The revenues from its wartime boom had allowed the commission to make significant investments in education, infrastructure, health care, pensions for disabled veterans and their families, and even loans and gifts to Great Britain.

The colony also inherited vast amounts of military property and infrastructure. In St. John’s alone, this included two hospitals, the RCN/RCAF headquarters, a naval barracks complex, a tactical training centre and numerous other area properties.

RCAF Air Station Torbay eventually became St. John’s International Airport.

St. John’s Harbour was also transformed. Once what Collins describes as “a tangle of decrepit wharves and finger-piers,” the RCN brought the moorings along the harbour’s Southside to naval standards—in most cases upgrading the owners’ properties with paving, fencing, access, etc. The navy built new facilities such as HMC Dockyard, now the Port of St. John’s shipping terminal, and a fuel tank farm, which was sold to Imperial Oil in 1946.

Three hospitals—in Gander, Botwood and Lewisporte—were added to the health-care system. A fourth, the U.S. Memorial Hospital in St. Lawrence, was officially opened on D-Day’s 10th anniversary, a gift from the U.S. government to the people of St. Lawrence and Lawn who rescued and cared for survivors of the February 1942 disaster in which two U.S. naval vessels, Pollux and Truxtun, ran up on nearby rocks in a storm.

Hundreds of kilometres of roads were laid during the war. The Newfoundland Railway was expanded with new rail lines and rolling stock. Modern communications systems were installed and augmented, navigational beacons were upgraded, and Long Range Navigation (LORAN) added.

During succeeding decades, the Americans—and to a lesser degree the Canadians—closed facilities at St. John’s, Argentia, Botwood, Lewisporte, Gander, Stephenville and Goose Bay, passing title to federal, provincial or municipal governments.

Collins says the social impact of the war’s “friendly invasion” was also substantial.

“With the arrival of thousands of young men in communities throughout Newfoundland, many away from home for the first time, social interaction between the genders was inevitable,” he wrote.

“Scores of local women attended the various functions both on the bases themselves…and also at local entertainment facilities and hostels that sprang up at St. John’s and communities across the Island.”

“The war in Europe is over!”

And so, too, to a large degree, were the days of Newfoundland’s failing economy and starving populace.

Marriages, pregnancies—and sexually transmitted diseases—increased dramatically until U.S. authorities stepped in and prohibited local marriages, even sentencing some love-struck young bucks to prison terms.

“The Canadians, while not encouraging such unions, did not prohibit them, and seldom did a week go by that the St. John’s Evening Telegram did not announce an engagement or marriage between ‘a local girl’ and a visiting serviceman.”

When it was over, locals tended to join their spouses in Canada or the United States. Some would return to Newfoundland and raise families.

The friendly invasion changed Newfoundland and its people, who in turned changed the “invaders,” many of whom had never been far beyond their own villages and towns.

The colony never returned to dominion status. In 1948, fearful the United States would make a play for ownership of what was now recognized as a strategic chunk of North American territory, Britain and Canada conspired to omit the American option from two referendums on the colony’s future.

With Joey Smallwood at the helm, confederation with Canada edged out British rule and outright independence in a result whose legitimacy is in some quarters debated to this day. Newfoundland entered Confederation on March 31, 1949.

For years, it would be considered a “have-not” province, the breeder of Alberta oil workers and recipient of billions of dollars in equalization payments from its wealthier siblings. Until, that is, offshore oil and gas propelled the renamed province of Newfoundland and Labrador to a payer between 2008 and 2024.

In today’s changing and once-again increasingly volatile world, the province’s strategic importance, at the intersection of the Arctic and eastern approaches to the continent, cannot be overstated.

Nor can the value of its people who, in 75 years, have changed Canada, too.

“Among English-Canadians, at least,” author and historian Gwynne Dyer, a dyed-in-the-wool Newfoundlander, wrote in a 2003 royal commission report on the province’s place in Canada, “Newfoundlanders have come to be seen as a slightly different breed of human beings who add interest and value to the Canadian mix.

“There is a clear perception among urban Canadians in particular that both the place and its people are in some sense special. If you were to press them as to what that really means, they would reply using words like ‘authentic’, but also words like ‘articulate’—not picturesque rural idiots, but people whose ideas and values have substance, and who know how to express them.

“If your most important possession is your reputation, then Newfoundlanders have not done badly over the past half-century—or at least we have done well at distracting attention from what we have done badly.”

Allied merchant ships in the harbour decorated with flags mark the end of the war in Europe. [CWM/19840030-100]

Advertisement