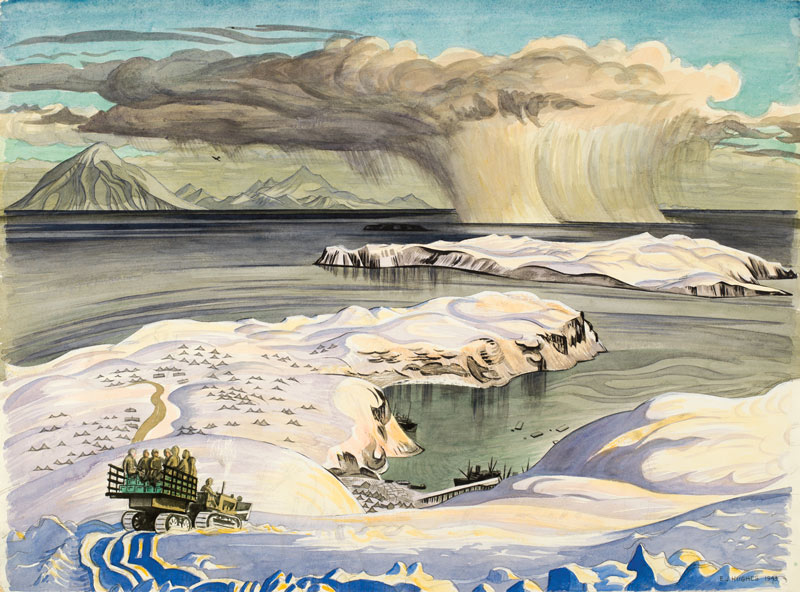

Captain E.J. Hughes depicts a snowstorm passing as soldiers head to Alaska’s Kiska Harbor[E.J. Hughes/CWM/19710261-3452]

Alaska’s Aleutian Islands have a violent beauty to them, crowned with steep cliffs, 2,000-metre-plus-high mountains and active volcanoes, all protected by the white horses of ocean waves. Cold and brooding, the islands stand in hushed resistance between life and death.

Many don’t know, however, that this archipelago to the southeast of the Bering Sea had a place in the memories of some Second World War veterans. Like toy soldiers stored in an attic, the Aleutian Islands Campaign is largely forgotten.

“[It was] the weirdest war ever waged,” said a B-24 bomber pilot who participated in the campaign. And given the limited strategic value of the island chain, along with its frequent storms, high winds and relatively barren landscapes, there might be stock in that depiction.

The campaign took place from June 1942 to August 1943. It started when the Japanese bombed, then seized, the sparsely populated Attu and Kiska islands. Historians believe the move was designed to either divert American troops from the central Pacific or hinder the U.S. from invading Japan through Alaska.

Canadians were called on to help the Americans, and the Allies ultimately prevailed, battling as much with the land as they did with the Japanese.

“Weather was their worst enemy,” said Karen Abel, former historical consultant for the U.S. National Park Service whose grandfather Robert W. Lynch was a Royal Canadian Air Force fighter pilot who served in the Aleutians with No. 111 (Fighter) Squadron. Indeed, most of the Canadian casualties were caused by the weather.

The campaign was one of the deadliest in the Pacific during the war and the only action fought on North American soil. Canada’s contribution was its army’s second largest in the Pacific theatre. Still, it’s considered the “Forgotten Battle.”

Said Abel: “144,000 people were stationed up there, and nobody knows.” But the memories still live.

Just months after its surprise strike on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on Dec. 7, 1941, the Japanese launched another offensive in the eastern Pacific, bombing the U.S. naval facility at Dutch Harbor on Amaknak Island in the Aleutians on June 3-4, 1942.

The Japanese invaded nearby Kiska Island days later, on June 6, and Attu Island the following day. The invaders met little resistance from the local Indigenous Aleuts who were subsequently sent to internment camps. The Japanese proceeded to set up defences and within a year, there were 5,400 troops on Kiska, 2,500 on Attu.

“This enemy incursion into the North American zone was necessarily a source of grave anxiety to Canada as well as the United States,” wrote Colonel Charles P. Stacey in his official history of Canada’s role in the Second World War.

Smoke rises from the state’s Dutch Harbor after a Japanese bombing attack on June 3-4, 1942. [U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command/80-G-215398]

The Americans responded with air attacks on the islands, and worked to occupy others closer to them themselves. Canada, meanwhile, already had one RCAF squadron serving in Alaska at the time, at Annette Island at the state’s south end. Small forces of the Canadian Army, including anti-aircraft gunners and an aerodrome defence company soon joined them. And two other RCAF squadrons were en route; Max Crandall among them.

Born about 32 kilometres from Ponoka, Alta., in a district that was once called Chesterwold, Crandall was a farm lad with a brain for mechanics.

“I was a country boy in every sense of the word, a child of the Western Canadian farm,” wrote Crandall in his memoir Farm Boy Goes to War, one of the few first-hand Canadian accounts of the Aleutian Campaign.

Albertan to the core, his parents ran a farm, harvesting hay and grains and raising horses, pigs and cows.

“We had a great attachment for the land,” said Crandall. “The philosophy of morality, honesty, integrity, love of family and thoughts for others…was very much adhered to.”

To Crandall, though, living off the land didn’t just inspire character—it came with the hands-on knowledge of working with machines. That combination of attributes made Crandall and other farm boys prime soldier material.

Machinery and its production matured into a powerful force during the Second World War. The dawn of mass production, better vehicles and advanced electrical transmission allowed for a new type of war.

The Industrial Revolution had transformed agriculture by the 1920s and ’30s, so recruiters turned to young men from rural communities for enlistment in the Second World War.

“These young boys grew up with and knew the basics of modern machinery,” noted Crandall. “They also knew how to work and how to survive under the most trying circumstances.”

And trying circumstances they were. The ’30s played dirty on Canadian farming, with little money and even less food to be spared. As many as 750,000 farms across Canada were lost to drought, pests and the nation’s economic collapse in the Great Depression.

“In 1939, it must have seemed that the depression would never end,” noted Bill Eull, a retired psychologist behind the 111 Squadron history project website (see “Keeping the Aleutians Campaign alive,” page 23). “Especially farm workers, having had a decade of discouragement.”

Dirt poor, Crandall and others like him were hungry for opportunity, believing war was the way to the educational and employment advancement. But there was more, too.

“The natural desire for people to fight and win; the yen for adventure,” said Crandall. “It must have been the glory of the fight—that indefinable something that makes young people sacrifice their lives for ‘love and glory.’”

Crandall enlisted at 19.

It was an ordinary Sept. 10 for Crandall and many other Canadian farmhands in 1939. Chesterwold wasn’t much for radio access, leaving it up to the Ponoka townies, Edmontonians and the like to irrigate the trickles of news they gathered. On that day on Crandall farm, Canada’s declaration of war had yet to stop the bushels from bowling.

So it was that Crandall’s brother Jay, who ran his own radio business, came to relay the news.

“Many of us were at home but none said much,” said Crandall. Four of his brothers subsequently enlisted before he did, too.

Crandall mulled the idea of what war role fit him best, but his penchant for planes gave him a hint. Calgary’s RCAF recruiting centre, however, gave him another.

“They didn’t really want me in aircrew anyway; everyone wanted to be a pilot,” said Crandall.

Settling for ground crew, Crandall became an armourer after five weeks of basic training in Toronto and armament school in Mountain View, Ont. He was posted to 111 Squadron in Patricia Bay, B.C., in February 1942.

A Kittyhawk of 111 Fighter Squadron refuels at Patricia Bay, B.C. [LAC/PA-501021]

“It had to have been a stroke of luck, for…a finer group of servicemen, on the whole, you wouldn’t find anywhere,” wrote Crandall.

No. 111 had been formed in November 1941, the third of six units originally meant to be shipped to Europe. But when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, those plans changed. In December 1941, the squadron had been sent west to Patricia Bay, near the present site of the Victoria International Airport.

“The biggest casualties were people who had…frozen limbs.”

On the Aleutian Islands, nature was the enemy to anyone, Allied or Axis. Indeed, as Stacey wrote: “the enemy led a precarious and uncomfortable existence.”

Canadians such as Crandall boarded the SS Catala in Sidney, B.C., on June 6, 1942, and hopscotched up coastal islands toward Alaska. But when the ship docked at Annette Island, any expectations of a battlefield worth dying on faded fast in rain and fog.

“Disappointment reigned supreme,” said Crandall.

Not more than a day later, Crandall was seabound again, this time on the Denali to Anchorage. And the closer 111 Squadron got to its station, the rougher the water became.

A Hughes watercolour illustrates soldiers using a guide rope to get back to camp amid the Aleutians’ blistering winds[E.J. Hughes/CWM/19710261-3220]

“When the waves started to look like mountains and the propeller of the Denali would come out of the water and spin around in the air…[there were] some very pale faces,” recalled Crandall.

The dangers of flying, sailing or simply existing on the Aleutian Islands came from its own unique geography where the Arctic freeze of the Bering Sea meets the warm waters of the Kuroshio, or Japan, Current.

“We get four seasons in five minutes,” Flying Officer Ronnie Cox told The Canadian Press of the conditions. Stacey noted: “Aleutian airmen found the weather more dangerous than the Japs.”

The combatants faced tough conditions, including frequent snow, rain, sleet storms, fog and dreaded williwaws, violent squalls that blow offshore from mountainous coasts. One pilot recalled a time when, after getting out of his plane to talk to the ground crew, he turned around to find his aircraft upside down.

“One writer has referred to this area as the birth place of the winds,” said Crandall, “and I have no reason to contradict his assessment.”

Two RCAF squadrons, 111 and No. 8 (Bomber Reconnaissance), eventually staged at Umnak, then Amchitka, islands—the latter just 130 kilometres from Kiska. Their role was primarily defensive, comprising a couple of flight operations with the U.S. Army Air Forces’ 11th Fighter Squadron. Otherwise known as “flagpole flying,” their day-to-day action consisted of reconnaissance patrols and intercepting both unidentified aircraft and radio transmissions. All the while, the Canadians wanted something more.

“They were chafing to get into action,” wrote Eull.

Crandall and some other members of 111 were stationed at Umnak, where the RCAF’s duties included daily dawn-to-dusk aerodrome patrols and evening discussions about war strategy with American pilots.

Hughes depicts soldiers at a canteen on Kiska Island in 1944[E.J. Hughes/CWM/19710261-3907]

But the living conditions weren’t just minimalist when Crandall arrived—they were primitive. Their tents weren’t built for the climate, so the men slept without proper insulation, buffeted by the winds and with rain seeping in. Plus, some reported not receiving Arctic-rated sleeping bags until two or three weeks into their stay, making the cold, wet ground an unfortunate mattress.

The mess hall was no escape from the cold either. “It was just an open-air tent,” said Abel. “One veteran said they’d have to slop all of their food together on their mess tray and eat in the cold or bring it back to your tent [but] by then, it would get cold.”

But hot food wasn’t common anyway, with canned sweet potatoes or peaches the dietary status quo. Shipments, however, would sometimes go awry, leaving the men to eat the same food day after day—or simply nothing at all.

One of the veterans said, “To this day, I still can’t eat a sweet potato,” recalled Abel.

Alcohol was equally scarce, and many men resorted to drinking lemon extract, shoe polish or “torpedo juice”—pure alcohol allegedly from used torpedoes—to get a buzz.

On top of that, many went without the standard parkas, shoepacks and winter gloves; troops were often left to wear field jackets, Blucher boots and wristlets.

“Those guys went north with clothing…suitable for warm weather,” remarked Eull. “The biggest casualties were people who had…frozen limbs.”

In those days, some truly felt like they were living on mud and glory—and that made not only the body a casualty, but the mind as well.

Wrote Crandall: “We were just waiting for sunshine.”

“144,000 people were stationed up there, and nobody knows.”

Dark skies can make for dark minds, especially when they are left to their own devices.

“With persistent intermittent rain and never a ray of sun, some depression set in,” reported Crandall. “There was nothing to do and nothing to read.”

While volleyball and some hockey were reportedly played, a crushing boredom and severe isolation persisted throughout the island, with connections to civilian life weak and weathered.

“We could expect to get mail about once a month or a little better,” said Crandall.

Not surprisingly, this took a toll on morale, leaving minds to wander to maddening places. Medical officer Robert J. Cowan of 111 said that men would often appear in the medical tents for wounds that were a bit more difficult to spot.

“For some of them the stress of the isolation, the absence from their families, and other problems were taking a toll,” said Cowan.

“The real problem here, of course, was the old phenomenon known in the north nearly a half century earlier as cabin fever,” said Crandall, “and its side-kick, loneliness.”

Crandall noticed the particular effects the conditions had on senior non-commissioned officers. Many NCOs would often build doors and walls to their tents out of packing crates, and sometimes, that makeshift shelter became their late-night target practice.

“They began shooting through the door and it became risky business,” wrote Crandall. “It was just the sheer loneliness of their position.”

Even through rough times, the soldiers found unique ways to improve each other’s lot. Crandall claims to be responsible for borrowing the idea of pitching tents in holes from the Americans to help keep out of the elements.

In October 1942, Crandall’s unit moved to Kodiak Island, where conditions improved tremendously for the unit, finally having access to restaurants, libraries and entertainment. His squadron would stay at Kodiak until the end of the Aleutian Campaign.

“Kodiak was…like an oasis in the desert,” said Crandall.

During their time there, 111 was responsible for protecting the U.S. naval base.

With the Allied bombing campaign ineffective in evicting the Japanese from the islands—and with a local naval blockade similarly futile—the Americans launched a ground assault on Attu on May 11, 1943. Some 15,000 U.S. troops participated in the two-plus-week battle.

“It ended in complete annihilation of the Japanese defenders, who made their final Banzai charge on 28 May,” wrote Stacey. “The Americans took eleven prisoners; all the rest were killed in action or committed suicide.” Some 2,500 dead.

Members of the 13th Canadian Infantry Brigade play cards in July 1943 while waiting to advance on the island. [LAC/PA-177681]

With Attu in Allied hands, plans were quickly made to recapture Kiska. And Canada stood to take a much larger role. Its contribution included the Canadian component of the First Special Service Force and four infantry battalions: The Canadian Fusiliers (City of London Regiment), The Winnipeg Grenadiers, The Rocky Mountain Rangers and Le Régiment de Hull. The 24th Reserve (Kootenay) Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery, and some smaller units completed the group. It totalled 4,800 troops.

But when they went ashore on Aug. 15, they met no resistance. Within a couple of days, it was clear that the Japanese had evacuated. By Aug. 24, the island was declared secure by the Americans, thus ending the campaign.

While members of 111 Squadron such as Crandall never saw explosive fighting in the Aleutians, they did witness its impacts, with many Canadian troops meeting with American soldiers post-battle. As one of the squadron’s acting sergeants recounted to his son: “It must have been rough. Those commandos were a tough bunch.”

American soldiers during the attack on Attu Island.[U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command/LC-Lot-803-34]

Keeping the Aleutians Campaign alive

“I’m not a historian by nature,” said Karen Abel, “I’m a historian by passion.”

Abel runs the blog, “Florida Beaches To The Bering Sea,” where she shares wartime documents from her grandfather, RCAF 111 (Fighter) Squadron fighter pilot Robert W. Lynch (below), and interviews with dozens of families, to document the Aleutian Islands Campaign. Her efforts have been recognized by numerous publications and the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum.

Bill Eull, meanwhile, uses his website dedicated to the 111 Squadron (www.rcaf111fsquadron.com) to bring the relatives of more than 50 families affected by the Aleutian Campaign together. He has also amassed a detailed database of those who served in 111.

[Karen Abel/www.floridabeachestotheberingsea.com ]

Advertisement