Delegates attend the first meeting of the Canada-U.S. Permanent Joint Board on Defence in August 1940, a precursor to Norad.[U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command/NH 91719]

When U.S. military officials publicly shared news of a suspected Chinese spy balloon floating some 18,000 metres over Montana early this past February, they indicated that the North American Aerospace Defense Command (Norad) had been tracking it for several days. It was Norad’s most noteworthy moment since 9/11. In the following days, the organization identified three other mysterious objects floating over the continent, including a small, cylindrical object that was shot down by a U.S. F-22 fighter jet over the Yukon on the orders of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. In a week, Norad had shown what it does and how.

When Canada and the United States formally established the North American Air Defense Command (Norad) on May 12, 1958, it was to protect against a possible Soviet air attack during the height of the Cold War. But it was not the first bilateral defence agreement between the two countries. That occurred on Aug. 18, 1940, when Prime Minister Mackenzie King and President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Ogdensburg Agreement, which created the Permanent Joint Board on Defence.

The board, comprised of Canadian and American military personnel and civilian research scientists, was a forum for communication between the two countries and to deliver assessments about “the defence of the north half of the Western Hemisphere.” Although created during the Second World War (even though the United States was not yet a belligerent), the board was intended to be a permanent organization and to outlast the war.

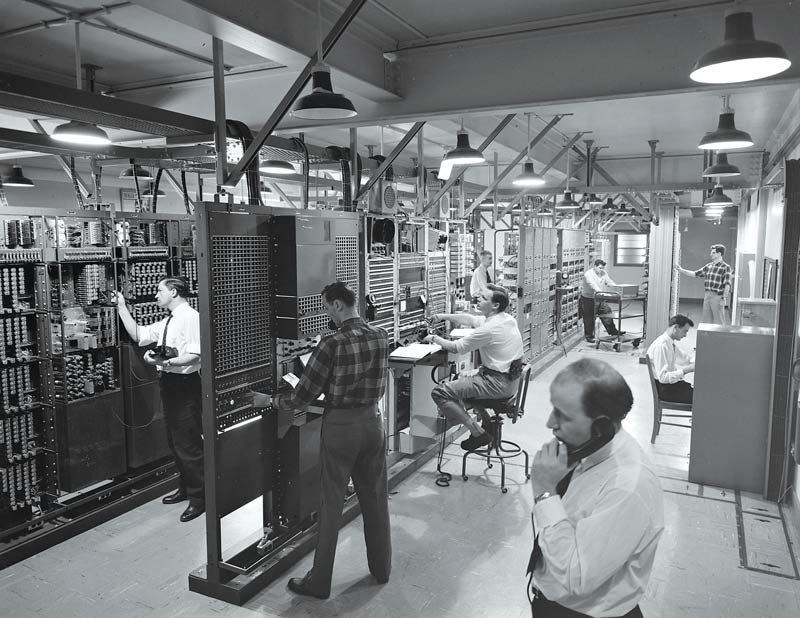

Its early collaborations included building three radar networks, the Pinetree Line( in picture), the DEW Line and the Mid-Canada Line.[Alex Saley/LAC/e0113113703]

The membership of the board expanded in recent years to include representatives from Public Safety Canada and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

The next step in bilateral continental defence arrangements was the establishment of the Military Co-operation Committee in 1946. The committee is the main strategic connection between Canadian and American joint military staffs.

The establishment of Norad followed, and it’s the most comprehensive of all bilateral defence agreements between the two countries. Although it came about after a series of meetings between representatives of Canada and the U.S., Norad had its beginnings in unilateral actions taken by the Americans to create a defensive air shield against possible attacks by long-range, manned Soviet bombers.

Its early collaborations included building three radar networks, the Pinetree Line, the DEW Line and the Mid-Canada Line( Above)[Malak Karsh/LAC/e011177255]

In the late 1940s, the United States Air Force (USAF) created Air Defense Command, which, in 1954, morphed into the tri-service Continental Air Defense Command. As American planners looked toward the future, it became obvious co-operation with Canada was a necessary part of continental defence.

Early collaboration consisted of building three radar networks across Canada. The first was the Pinetree Line, which became operational in 1952-53. Eventually, it consisted of 44 long-range radar stations, augmented by several “gap filler” sites. Stations were manned either by Royal Canadian Air Force or USAF personnel. The stations stretched across Western Canada at roughly the 53rd parallel, and the 50th parallel in the east. An extension along the eastern seaboard ran from Nova Scotia up the coast of Newfoundland and Labrador to the Northwest Territories (present-day Nunavut).

The Pinetree Line cost $450 million to construct, of which Canada paid $150 million. Its stations closed over a period of several years, beginning in the mid-1980s. The last ones shut down in 1991.

The radars, and Norad, aimed to protect North America against possible Soviet air attacks from the likes of its Myasishchev M-4 long-range bomber.[Wikimedia]

Construction of the second of the radar networks, the Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line, began in December 1954. The DEW Line became operational on July 31, 1957—just 32 months after the decision was made to build it. The size and scope of the construction of the DEW Line in the Far North presented unknown challenges.

At the time, not much information was available about conditions in the Canadian Arctic, including topographical data, climatology, soil conditions, oceanography and construction difficulties. Settlements consisted of scattered Inuit villages, Hudson’s Bay Company posts and remote weather stations.

The line consisted of an integrated chain of 63 staffed radar and communications stations, which stretched some 4,800 kilometres from the coast of northwestern Alaska across northern Canadian tundra to the eastern shore of Baffin Island at roughly the 69th parallel, about 300 kilometres north of the Arctic Circle.

Canadian divers prepare for an underwater survey during work on the DEW Line in 1957.[LAC/e011176474]

The construction of the DEW Line was the largest project ever undertaken in the Canadian Arctic. It took about 25,000 people to build the line and cost $750 million.

The DEW Line’s construction left a “mixed legacy” according to Natan Obed, president of Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, a national Inuit organization. Although it provided employment for Inuit and left several communities with permanent infrastructure, including core aviation facilities, it “was not conceived with the specific needs of Inuit in mind.”

Meanwhile, defence officials from both countries had been discussing the integration of air defence plans. Details of a comprehensive agreement were determined and Norad was the result. The new command stood up on Sept. 12, 1957, with headquarters at Ent Air Force Base in Colorado Springs, Colo.

Local Inuit children pose with workers near a DEW Line site a year earlier[Alex Saley/LAC/e011313693]

Norad’s motto is “We have the watch.” From the beginning, Norad’s commander was a USAF general, while the deputy commander was an RCAF air marshal (lieutenant-general after the unification of Canada’s forces).

Nine months after Norad launched, Canada and the U.S. announced the formalization of the agreement on May 12, 1958. Part of the pact specified periodic review, which ensured Norad could adapt as the threats to the two nations changed with time and technological advances.

Meanwhile, a third string of radar defences, the Mid-Canada Line (MCL)—also known as the McGill Fence—was conceived in the early 1950s, but did not become fully operational until January 1958. This chain was intended as a second line of detection for any enemy aircraft that had penetrated the DEW Line.

Men oversee Mid-Canada Line radar.[Malak Karsh/LAC/e011177256]

Inserted between the DEW and Pinetree lines, it consisted of eight staffed sector control stations and 90 unstaffed Doppler detection stations along the 55th parallel. It stretched some 4,000 kilometres from British Columbia to Labrador and cost about $225 million to build.

Although the construction of the MCL didn’t encounter the same problems associated with building the DEW Line, it was a difficult job in the rugged subarctic tundra of rocky bush, countless lakes and unforgiving muskeg. Within a few years, however, the MCL was shut down. The reason? Improvements in technology and the design of jet aircraft made the MCL no longer economically feasible or strategically necessary. The western sites were decommissioned in January 1964, while the eastern ones closed in April 1965.

A near run thing

Canadian Air Marshal Roy Slemon was the first deputy commander of Norad [Wikimedia]

Air Marshal Roy Slemon (1904-1992) was the first deputy commander of Norad. Slemon was born in Manitoba and joined the Canadian Air Force in 1923, where he became one of the first Canadian pilots to earn wings in peacetime. During the Second World War, he served in Britain and became deputy commander of No. 6 (RCAF) Group of the Royal Air Force Bomber Command. By the end of the war, he was the deputy air officer commander-in-chief of the Royal Canadian Air Force overseas.

Slemon became the RCAF’s chief of air staff in 1953, then Norad deputy commander in 1957. On Oct. 5, 1960, radar signals from Thule, Greenland, suggested a missile attack from the Soviet Union was taking place. On learning Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev was at the United Nations, Slemon chose not to order a retaliatory strike. This was fortuitous, as the signals were later found to be radar beams bounced off the rising moon.

The DEW Line site at Cape Dyer, Nunavut, awaits the cleanup of toxic materials in 2012.[Richard Lauten/Toronto Star via Getty]

During the 1960s and 1970s, the threat from the Soviet Union quickly became more dangerous. The Soviets amassed a stock of intercontinental and sea-launched ballistic missiles and created an anti-satellite capability. As one observer noted, the northern radar chains could now “not only [be] outflanked but literally jumped over.”

In response, the USAF soon developed space-surveillance and missile-warning systems. They provide global detection, tracking and classification of objects and activities in space. These systems came under Norad control when they became operational.

In 1981, the “air” in Norad’s name was changed to “Aerospace.”

Between 1986 and 1992, the original radar stations of the Pinetree and DEW Lines were replaced by a chain of 50 new radar sites of the North Warning System (NWS). Some DEW Line sites were closed, while others were folded into the NWS. For those that closed, a lengthy cleanup process followed, which included the removal of toxic waste from 21 of the sites.

All NWS locations are remotely monitored from North Bay, Ont. The radar capabilities of the NWS have largely been overtaken by modern weapons technology, in particular advanced cruise missiles and hypersonic weapons.

The end of the Cold War in 1991 initiated major changes for Norad, driven by a strategy review. Although the threats had changed, they had not gone away. They also included new possibilities, such as cruise missiles or similar weapons being used by terrorists. To protect North American airspace against such dangers, Norad plans envisaged enhanced ground-based radar and airborne early warning and control system aircraft to detect missiles—and the planes to shoot them down.

New initiatives affected Norad in the early 2000s. As a direct result of 9/11, the U.S. Department of Defense stood up U.S. Northern Command, or USNORTHCOM, on Oct. 1, 2002. This new command plans, organizes and carries out homeland defence and civil support missions. It is integrated and aligned with Norad, while its commander also oversees Norad.

Canada and the U.S. have renewed and extended the Norad agreement several times. In 2006, the agreement was signed in perpetuity and added an important third mission: maritime warning. This new responsibility allows Norad to gather information related to the offshore areas and approaches to the two countries, identify potential marine threats and warn of any attacks against the continent.

A U.S. F-15C Eagle fighter jet participates in a simulated air defence over San Francisco in 2021. [Senior Airman Lawrence Sena/U.S. Department of Defense]

Operation Noble Eagle

There has only been one successful manned aircraft attack against the United States—and it came from within. The terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, which used four hijacked commercial airliners, resulted in 2,996 deaths, $10 billion to $20 billion in immediate property damage and thousands of short- and long-term injuries. It also profoundly changed the way we travel by air, perhaps forever.

It was also a wake-up call for Norad. Previously, the command’s mission to protect continental airspace was oriented to look outward. After 9/11, it was updated to include threats that could originate in the U.S. or Canada. Codenamed Operation Noble Eagle, Norad works with the Federal Aviation Administration in the U.S. and its Canadian counterpart, Nav Canada, to enforce temporary flight restriction areas (TFRs). If a pilot enters a TFR, Norad responds.

The U.S. conducts a test to intercept a medium-range ballistic missile near Hawaii in 2013.[Jessica Kosanovich/U.S. Department of Defense]

Ballistic missile defence

In February 2005, Prime Minister Paul Martin announced Canada would not participate in the U.S. ballistic missile defence program, which disappointed the country’s key ally. Then, in May 2022, Defence Minister Anita Anand stated Canada would examine the possibility of joining the American initiative as part of a major review of continental defence. “We are leaving no stone unturned,” Anand added, promising she would have more to say in the months to come.

The NWS has long been overdue for substantial upgrading and, although successive Canadian governments have stated it’s a priority, nothing had been done until recently. In January 2022, Canada awarded $592 million for a seven-year preventative and corrective maintenance contract for the NWS to an Inuit-operated company. The deal included options for four, two-year renewals, which, if invoked, would bring the contract total to $1.3 billion.

Today, Norad is concerned about the threat of hypersonic missiles, such the one carried by this Russian Mikoyan MiG-31 fighter jet.[Sefa Karacan/Anadolu Agency/Getty]

But the essential question of upgrading or replacing the NWS remained. In the fall of 2021, Norad commander, General Glen VanHerck, warned top Canadian government and military officials that the threat hypersonic missiles posed to continental security made it “very challenging” for him to carry out his mission. Arctic defence specialist Rob Huebert, meanwhile, believes the Russia aerospace and maritime danger to North American security “is real and it’s growing” and agrees the NWS is no longer adequate.

Then, on June 20, 2022, Defence Minister Anita Anand announced the federal government would spend $4.9 billion over the next six years to modernize continental defence. The overhaul will include replacement of the NWS with two new radar chains, one along the Canada-U.S. border and a second in the Arctic Archipelago.

Although many details are absent, defence analyst James Fergusson expects most of the money will be spent in the North. Minister Anand also said northern and Indigenous communities would be involved in the project from the start.

For Huebert, the main concern is timing. Is the government “going to follow through with quick action or are we going to see more delays?” he asks. Given Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, he hopes the government “will move fast.”

Advertisement