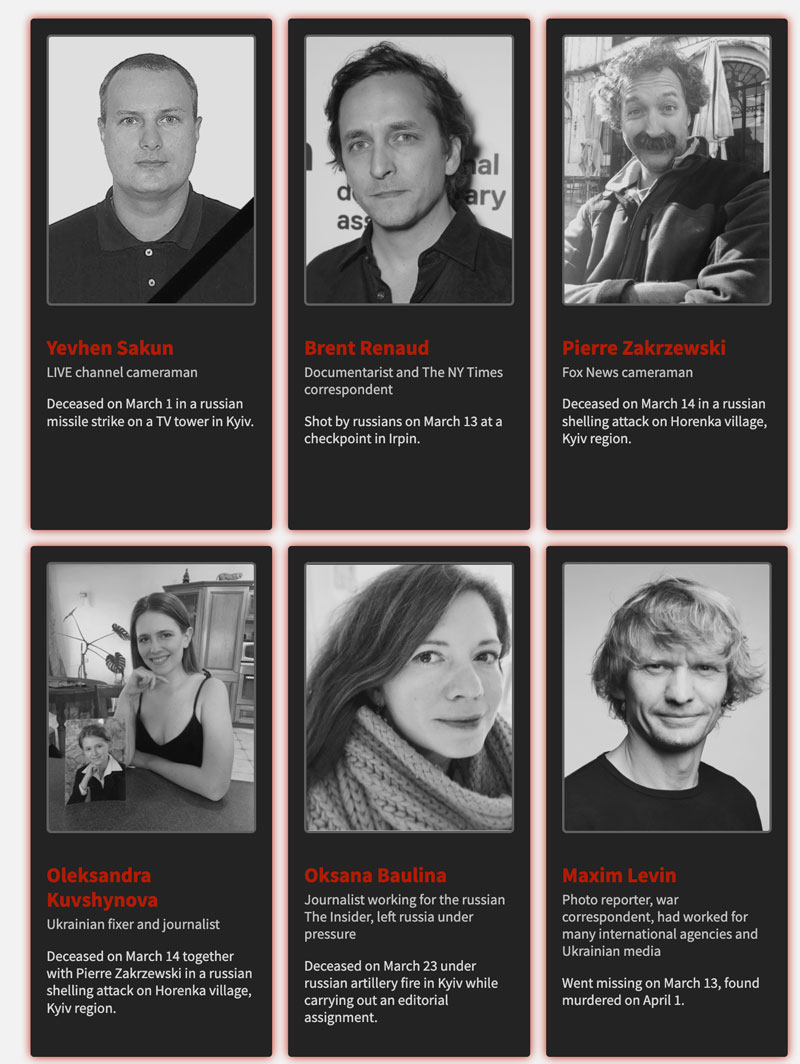

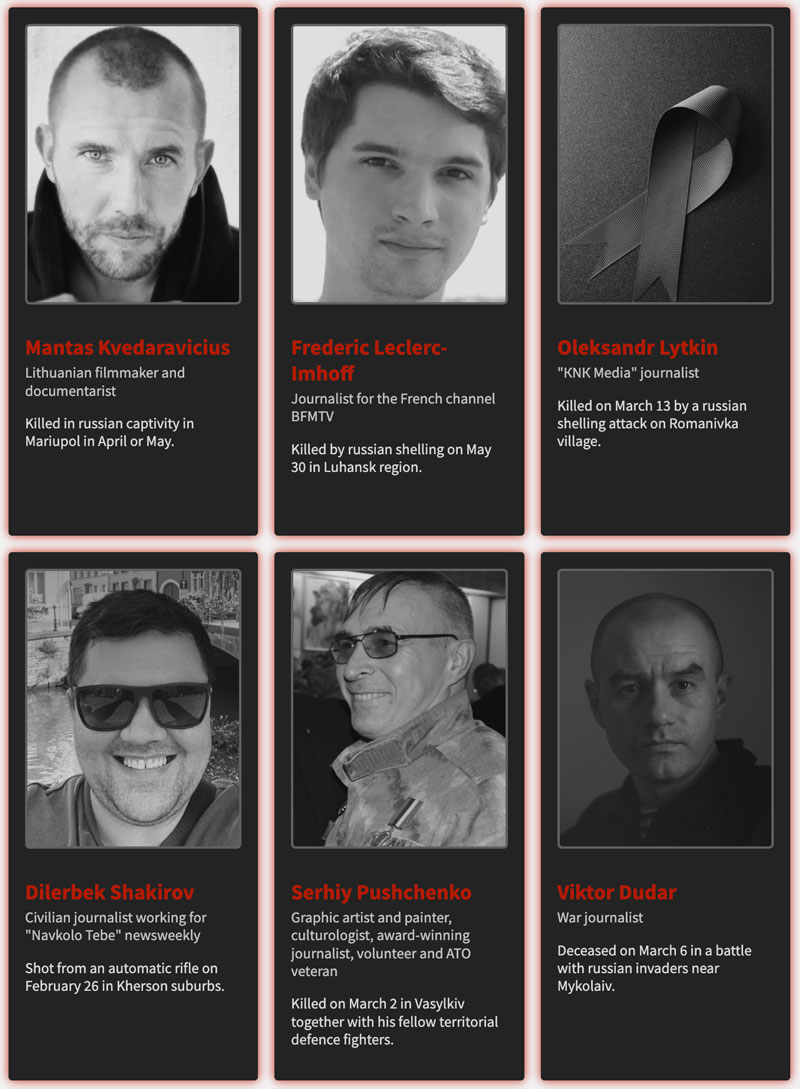

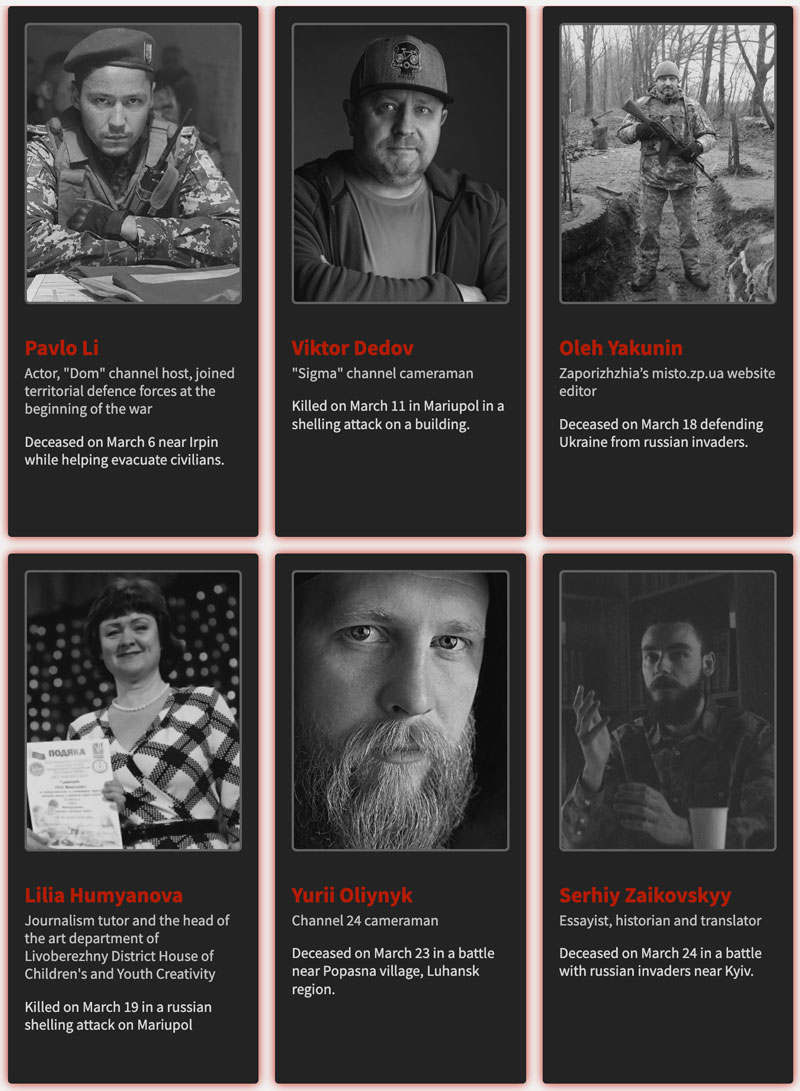

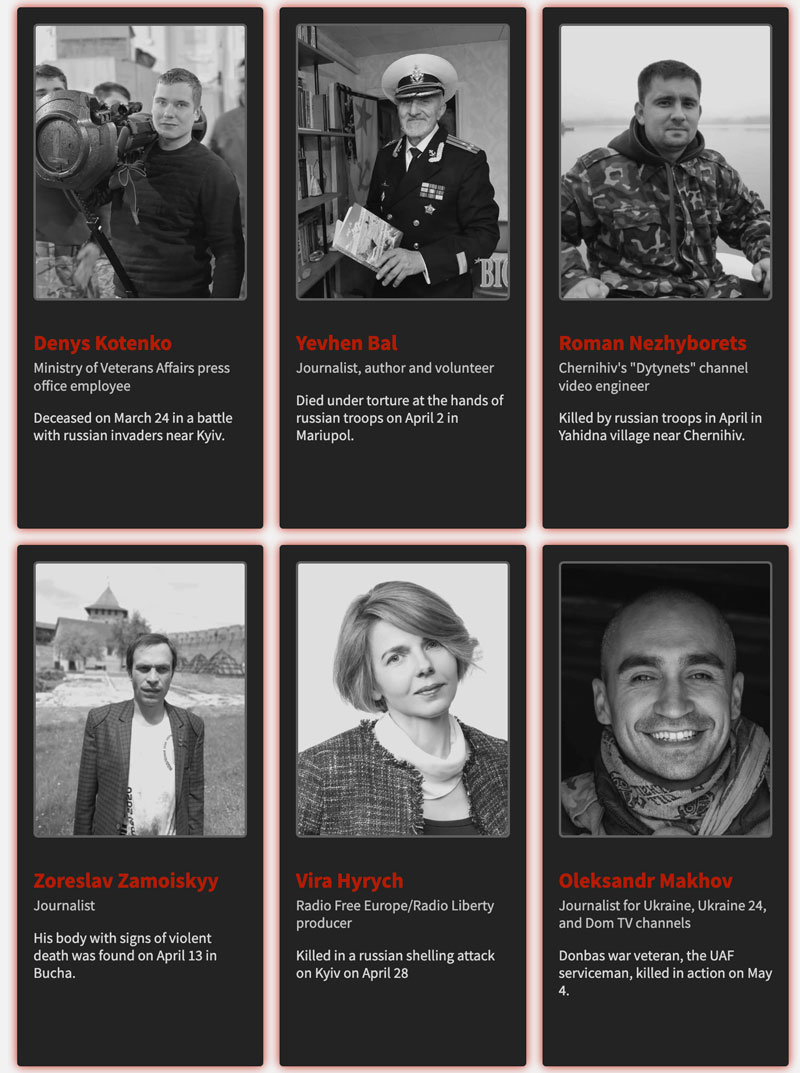

Ukraine’s list of journalists killed since the Russian invasion includes reporters and other industry workers who had joined the fight. [Ukraine Institute of Mass Information]

Culture and Information Policy Minister Oleksandr Tkachenko made the announcement on June 6, Ukraine’s national Journalist’s Day. It came 103 days into the fighting.

“This year’s Journalist’s Day has a special taste of bitterness,” said Tkachenko. “The fourth month of a full-scale war—and we lost 32 journalists. In eight years of war we lost even more. Eternal memory to our fighters of the advanced information front.”

The rolling figure threatens to exceed last year’s total as compiled by the International Press Institute “Death Watch,” pegged at 45 journalists killed on the job around the globe. Its data indicated no Ukrainian journalists died in 2021.

According to the Kyiv-based Institute of Mass Information, several of the Ukrainian nationals listed among those killed had left their news jobs and died while fighting with the country’s military.

The dead include working journalists killed during nearby fighting and munitions strikes, as well as those known to have been targeted by Russian forces.

The figure was tallied by the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine. Other sources put the number of dead working journalists considerably lower. Reporters Without Borders (RWB) said at least eight had died by May 30, including two Americans, an Irishman, a Frenchman, a Lithuanian, a Russian and Ukrainians.

“Since the start of the invasion, [Reporters Without Borders] had already registered 50 events affecting around 120 journalists that qualify as war crimes,” the group said after the May 30 death of French reporter Frédéric Leclerc-Imhoff.

Leclerc-Imhoff was sitting in the front seat of a humanitarian truck in Lysychansk when shrapnel from an exploding shell pierced its reinforced windshield and struck him in the neck.

The Paris-based RWB said it had filed its fifth complaint with the International Criminal Court’s chief prosecutor and with Ukraine’s prosecutor general, “and is continuing to analyse attacks targeting reporters.”

“The fourth month of a full-scale war—and we lost 32 journalists.”

French reporter Frédéric Leclerc-Imhoff (top centre) was killed in Ukraine just a week before the country’s national Journalist’s Day. [Ukraine Institute of Mass Information]

Its website lists all 32 dead, including a number who were no longer practising journalists.

Among them is Kostyantyn Kits, a cameraman for Avers Channel in Lutsk, who was killed in May “on the frontline defending Ukraine.” His picture shows him in battle fatigues, rifle in hand.

Yevhen Bal, a journalist, author and “volunteer,” was tortured to death by Russian troops on April 2 in Mariupol. Vitaliy Derekh, a journalist from Ternopil, a city of more than 200,000 in western Ukraine, was killed in action while serving with Ukrainian forces on May 28.

As non-combatants, journalists must be unarmed. It is a fundamental tenet of war reporting. Carrying weapons and equating journalists-turned-fighters with those who died plying their trade compromises the integrity of all journalists and places every reporter, field producer, photojournalist and their support teams at risk.

The institute report accuses Russian troops of kidnapping at least six journalists, threatening another 11, and intentionally targeting media facilities and reporters.

Several of the Ukrainian nationals listed among those killed had left their news jobs and died while fighting with the country’s military. [Ukraine Institute of Mass Information]

The UN has since documented at least 15 disappearances involving journalists and activists.

The United Nations said journalists must be treated as civilians during armed conflict and any attempt on their lives constitutes a war crime, adding that states have a “duty and obligation” to respect international humanitarian law.

The UN also warned that journalists, as well as local Ukrainian officials and “civil society activists” opposing the invasion, had been subjected to “enforced disappearances” believed to have been carried out by the Russian military.

UN-appointed rights experts and the UN special rapporteur on freedom of expression cited “numerous reports” that journalists were “targeted, tortured, kidnapped, attacked and killed, or refused safe passage from cities and regions under siege.” The UN has since documented at least 15 disappearances involving journalists and activists, and 22 involving local officials.

Maksim Levin was a 40-year-old photographer, videographer and father of four who had worked for Ukrainian and international media, including Reuters, for more than a decade.

Unarmed and wearing a press jacket, he disappeared near the heavily shelled village of Huta-Mezhyhirska on March 13. His body was found April 1. The prosecutor general’s office said Levin had been “killed by servicemen of the Russian Armed Forces with two shots from small arms.”

“We call on the Russian authorities to stop targeting journalists.”

Journalist Yevhen Bal (top centre) was tortured to death by Russian troops on April 2 in Mariupol. [Ukraine Institute of Mass Information]

“By taking hostages, after bombing TV towers and shooting at cars marked ‘Press,’ the Russian authorities are demonstrating their determination to censor all reporting that contradicts their military propaganda,” Jeanne Cavelier, head of RWB’s Eastern Europe and Central Asia desk, said in a statement.

“We strongly condemn these acts of intimidation and call on the Russian authorities to stop targeting journalists. They will have to answer for their actions before international courts.”

The first media worker killed after the invasion was Evgeny Sakun, a Ukrainian cameraman working for the local Kyiv Live TV channel, who died when Russian missiles hit the capital’s main television tower on March 1.

American Brent Renaud, a 50-year-old documentary filmmaker who had worked assignments for the New York Times, was shot in the back of the neck while driving in Irpin, northwest of Kyiv, on March 13. Juan Arredondo, a U.S.-Colombian reporter accompanying him, was wounded. The pair had been filming Kyiv’s exodus.

The next day, two journalists—Pierre Zakrzewski, a 55-year-old cameraman, and Oleksandra Kuvshynova, a 24-year-old Ukrainian journalist working as a fixer—were killed when artillery fire hit a Fox News crew in nearby Horenka. British journalist Benjamin Hall sustained serious shrapnel wounds in the attack.

On June 3, two Reuters journalists were wounded and their driver killed after the vehicle they were in came under fire while heading to the eastern Ukrainian city of Sievierodonetsk, a small factory city key to Russia’s ambitions in Luhansk province.

Photographer Alexander Ermochenko and cameraman Pavel Klimov were travelling in a car provided by Russia-backed forces. Reuters could not immediately identify the driver, who had been assigned to Reuters by Russian separatists.

Many more journalists have been killed during fighting since Russia annexed Crimea in 2014.

Italian photojournalist Andrea Rocchelli and Russian journalist and his fixer, activist Andrei Mironov, were killed on May 24, 2014, near the city of Slovyansk. The two men, along with French reporter William Roguelon and a local driver, were fired on by Russian forces as the crew walked to their car.

Roguelon said that they were then targeted by 40-60 mortars.

“We deplore the systematic crackdown on political opponents, independent journalists and the media.”

In Russia, the government recently labelled independent media “foreign agents.”

UN experts denounced Russian legislation that threatens 15-year jail terms for journalists “spreading ‘fake’ information about the war in Ukraine,” questioning what Vladimir Putin calls his “special military operation,” or “even mentioning the word ‘war.’”

“We deplore the systematic crackdown on political opponents, independent journalists and the media, human rights activists, protesters and many others opposing the Russian government’s actions,” said UN experts.

They urged Moscow to “fully implement its international obligations…by ensuring a safe working environment for independent media, journalists and civil society actors.”

Ukraine is ranked 97th of 180 countries in Reporters Without Borders’ 2021 World Press Freedom Index, while Russia is 150th—Canada comes in at 14th; the U.S. is 44th.

“Press freedom is defined as the ability of journalists as individuals and collectives to select, produce, and disseminate news in the public interest independent of political, economic, legal, and social interference and in the absence of threats to their physical and mental safety,” said the organization.

The International Press Institute (IPI) publishes its Death Watch annually. Of the 45 journalists whose deaths were documented in 2021, it said 28 were targeted due to their work, three were killed while covering conflict, two died covering civil unrest, and one was killed while on assignment. Eleven cases were under investigation.In the group’s parlance, “under investigation” means there are grounds to suspect a journalist’s death was a targeted killing, but more information is needed to confirm it.

Such is the case of former Reuters journalist Jess Malabanan in the Philippines, killed on Dec. 8, 2021, by assailants on a motorcycle. Malabanan, 58, had worked on an award-winning Reuters project in 2018 about President Rodrigo Duterte’s drug war.

A Duterte spokesperson called Malabanan’s death a “tragic murder” and urged witnesses to come forward. The Presidential Task Force on Media Security was looking into the incident, they said, and was “exploring all angles, including the possibility that the killing was related to his work as a journalist.”

IPI’s 2021 list included independent Somali journalist Jamal Farah Adan, shot on March 1. The extremist group Al-Shabaab later claimed responsibility. In July 2021, Mexican journalist Ricardo Dominguez López, owner of the news site InfoGuaymas, was shot to death in a supermarket parking lot on his 47th birthday.

The report said the Asian Pacific region was the deadliest for journalists in 2021, with 18 killings, most of which occurred in India and Afghanistan, with six apiece.

For the second straight year, more journalists were killed in Mexico (seven) in 2021 than any other country. All were targeted killings. Suspects have been arrested in only one of those cases.

Journalist’s Day in Ukraine is marked by a presidential order issued in May 1994, two years after the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine was admitted to the ranks of the International Federation of Journalists.

Advertisement