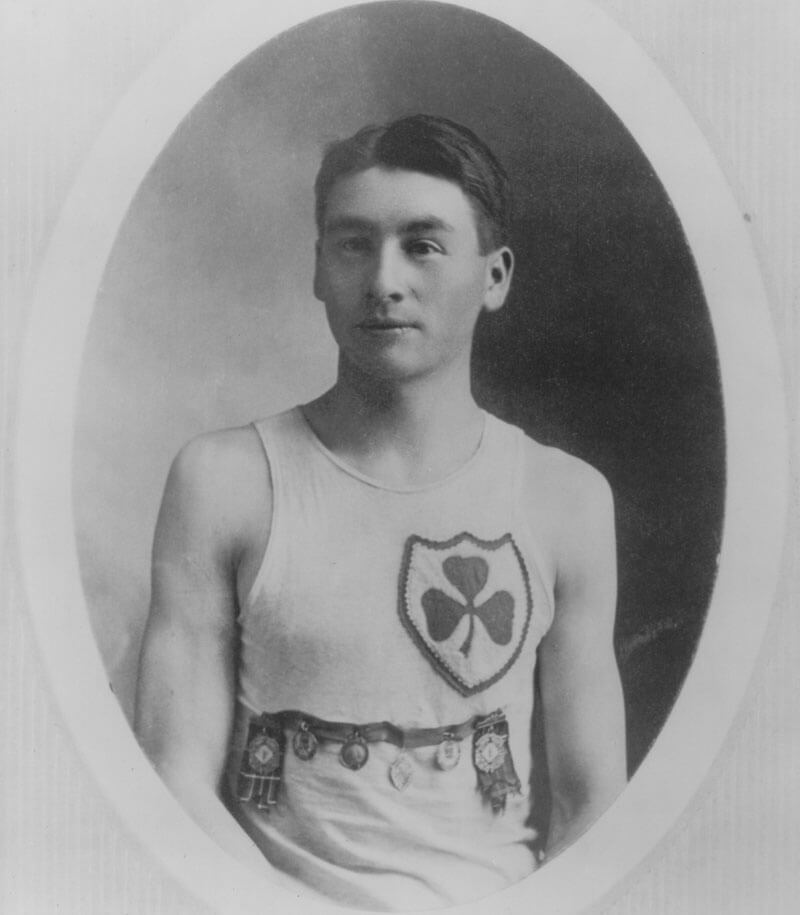

Alexander Wuttunee DeCoteau, born on Red Pheasant Indian reserve south of Battleford, Sask., was a farmhand, blacksmith, police sergeant and soldier. He was also a star runner who competed at the 1912 Olympic Games in Stockholm.

He left it all behind to join the Canadian Expeditionary Force in 1916 and was killed by a sniper’s bullet 18 months later during a morning attack on Oct. 30, 1917, near Passchendaele Ridge. He is buried in the Passchendaele New British Cemetery, 10 kilometres northeast of Ypres, known today by its Flemish spelling, Ieper (EE-per).

Now a private group organized by Belgian army veteran and battlefield guide Erwin Ureel plans to unveil a commemorative plaque on Indigenous Veterans Day, Nov. 8, at the site where DeCoteau died fighting with the 49th Battalion (Edmonton Regiment) late in the three-and-a-half-month Battle of Passchendaele.

“The plaque will not only be a personal tribute to DeCoteau himself,” said Ureel, “but also aims at making the public aware of the quite substantial participation of Indigenous Peoples [fighting for Canada] in the war effort.”

By the time the fighting ended more than four years later, untold thousands of Indigenous men had served. About 4,000 status Indians—a third of those eligible to join—signed up. No official count of Métis, Inuit or non-status First Nations volunteers exists.

“On 30 October 1917,” reads the proposed blue plaque to be posted alongside the road leading to the Canadians’ objective, “Alex DeCoteau, Age 29, 49th Bn Canadian Expeditionary Force, Member of the Cree Red Pheasant First Nation, Olympic athlete (Stockholm 1912), was killed in these fields on the Road to Passchendaele.” The plaque matches others that dot the surrounding countryside.

The fighting to gain and regain a few kilometres or even metres of ground exacted high costs on both sides.

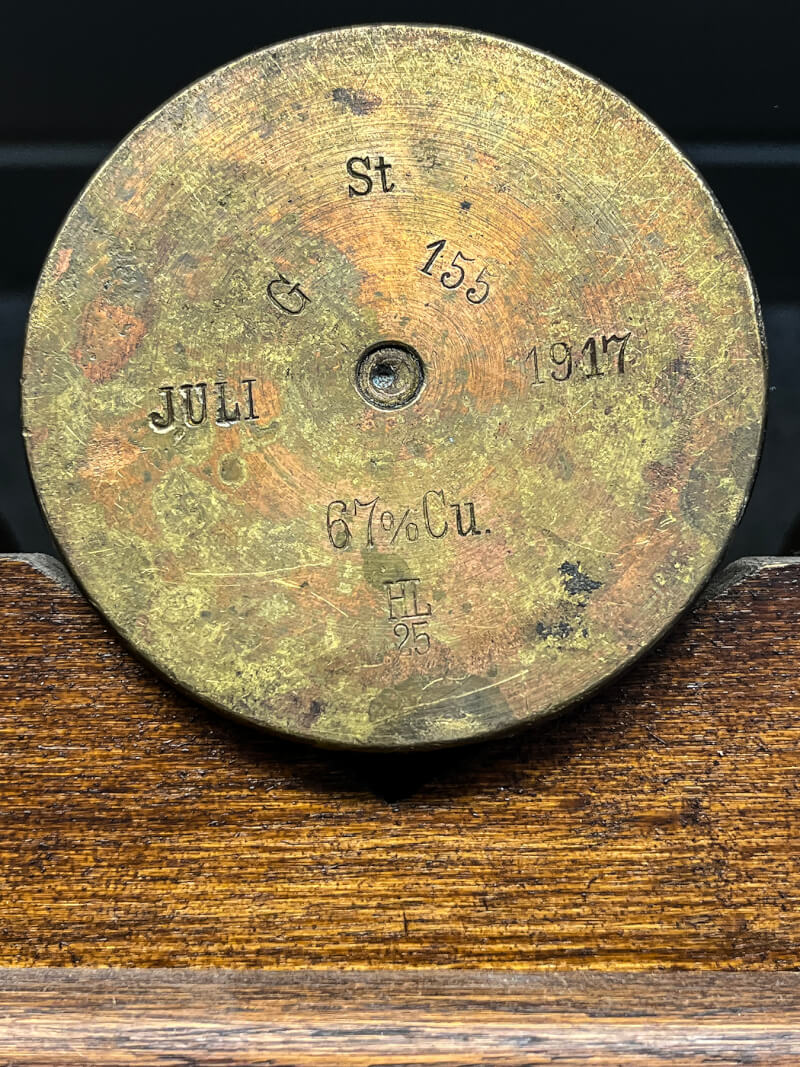

Known to many Canadians as the Battle of Passchendaele, the Third Battle of Ypres began in July 1917, almost three years after the German race to the sea ground to a halt in a salient around the medieval town of Ypres in west Flanders.

It is here, where the poppies grow north of the former trade centre, that Major John McCrae, a medical officer in the 1st Brigade, Canadian Field Artillery, treated wounded during the Second Battle of Ypres in 1915.

The Guelph, Ont., doctor-poet was inspired to write his famous poem “In Flanders Fields” after a friend was killed just metres from his hospital bunker. Shrapnel damage is still evident on the concrete face of his dank workplace.

Incessant artillery fire and periodic, bloody battles rendered the landscape a wasteland during the stagnant, muddy trench war that had formed along a 800-kilometre front through Belgium and northern France. There were five major battles around Ypres alone between 1914 and 1918 and, though the town and its surrounds were flattened, the Germans never broke through in any major way.

The fighting to gain and regain a few kilometres or even metres of ground exacted high costs on both sides. The Canadian Corps launched an attack in the Ypres sector approaching Passchendaele during a brief spell of dry weather on Oct. 22, with some success.

“When the 49th went in a week later, conditions had become much worse,” said a history collected by the Loyal Edmonton Regiment Military Museum. “The mud was so deep that movement was only possible on wooden duckboards.

“Trench systems dissolved completely. Dispersal was not an option, and moving up to attack position meant a heavy drain on manpower. Enemy domination of the air and the impossibility of finding firm platforms for field guns reduced the effectiveness of the artillery preparation.”

Just before 6 a.m., on Oct. 30, ‘B’ and ‘C’ companies of the 49th climbed out of their shell holes and began their advance in the face of devastating machine-gun fire on the outskirts of Passchendaele. The regiment’s commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Palmer, reported that ‘B’ Company lost most of its strength in the first 35 metres.

Total casualties to both sides numbered about 487,000.

Amid the carnage, Private Cecil John Kinross shed all his equipment except his rifle and bandolier, then charged a machine gun “over the open ground in broad daylight” and single-handedly killed its the six-man crew.

Kinross, who had moved to Lougheed, Alta., from his native Harefield, England, with his parents in 1912, was one of an unprecedented nine Canadians awarded the Victoria Cross for actions performed during the Passchendaele fighting.

“His superb example and courage instilled the greatest confidence in his company, and enabled a further advance of 300 yards to be made and a highly important position to be established,” said his citation.

Kinross was wounded in his head and arm in 1917 and subsequently hospitalized in England, where King George V presented him with the VC in March 1918.

General Douglas Haig, who had ordered the attack, maintained that the Flanders offensive was essential to relieve pressure on the French, whose army was shaken by mutinies in the spring and early-summer of 1917.

“But Haig never seemed to know when it was time to bring his attacks to an end,” said the unit history. “The later stages of Passchendaele in the fall of 1917 devoured battalions to no purpose, leaving the British army too weak to follow up on the breakthrough achieved by the first large-scale tank operation at Cambrai in November.”

After Canadian units made the final push into Passchendaele a week later, the 49th, along with the rest of the Canadian Corps, moved south to the relatively secure Vimy sector to recover and absorb reinforcements.

More than 4,000 Canadian soldiers died in the fight for Passchendaele and almost 12,000 were wounded. Total casualties to both sides numbered about 487,000.

The French mutinies, in which soldiers were willing to defend their positions but refused orders to attack after a costly defeat at the Second Battle of the Aisne, ended after General Robert Nivelle was sacked and replaced by General Philippe Pétain. More than a million French had died in battle by early 1917.

Pétain promised to end suicidal attacks, provide rest and leave for exhausted units and moderate discipline. He held 3,400 courts martial in which 554 mutineers were sentenced to death, but only 26 were executed.

DeCoteau was subsequently shipped off to residential school where he is said to have thrived.

DeCouteau is buried a few hundred metres from where he fell, flanked on one side by an unknown Canadian soldier of the 49th and Frank Liesmer, 22, a fellow 49er and farmer from Galt, Ont., who died the same day. On the other side lies Sidney Mark England, a 28-year-old private of the 43rd who died on the 26th. He survived a shrapnel wound in 1916. A Briton by birth, England enlisted in Brandon, Man.

DeCouteau had led a diverse and interesting life. His Métis father Peter joined the North-West Resistance and fought in the 1885 Battle of Cut Knife alongside Chief Pihtokahanapiwiyin (Chief Poundmaker). Peter DeCoteau was murdered in 1890 while working as an agent of the Indian Department.

DeCoteau was subsequently shipped off to residential school where he is said to have thrived, both academically and athletically.

Between 1909 and 1916 there was hardly a major middle- or long-distance race in western Canada that he did not win, according to The Dictionary of Canadian Biography.

At the July 1909 Mayberry Cup in Lloydminster, Sask., DeCoteau set a western Canadian five-mile record, finishing in 27 minutes, 45.2 seconds.

In 1910, he won the Calgary Herald’s six-mile-plus Christmas Day Road Race. He took the five-mile C.W. Cross Challenge Cup five times in its first six years. And in 1912, he won the annual 10-mile race at Fort Saskatchewan for the third straight year before earning a spot on Canada’s Olympic team.

In Stockholm, he finished second in his 5,000-metre heat, but he was plagued by leg cramps in the final and finished sixth, according to the Canadian Olympic Association.

In 1915 “the stalwart runner from the north,” wearing gloves, stockings and a toque pulled down over his face, won the Christmas Day race in Calgary for the second straight year—and an unprecedented third time.

He enlisted with the CEF in Edmonton the following April and died 20 days short of his 30th birthday.

“I brought her, together with a spiritual leader who was with her, for the first time in her life to the grave of Alex DeCoteau,” said Ureel. “It was a quite emotional occasion. That was also the trigger for the Alex DeCoteau run through the former Passchendaele battlefield we organized in 2007 and 2017.”

The Cree runner was inducted into the Edmonton Sports Hall of Fame in 1967 and, more than a century after he died, Edmonton students still gather each spring to run a five-kilometre race named in his honour.

Since DeCoteau had not had a Cree burial, his people believed his spirit had been left to wander the Earth. In 1985, his relatives and friends performed a ceremony in Edmonton to bring it home. Canadian army representatives and a 10-member Edmonton Police Department honour guard attended.

At least four other Canadian Olympians were killed fighting in the First World War:

- James Duffy—an Irish-born, Scottish-raised Torontonian—finished fifth in the Olympic marathon at Stockholm before winning Boston in 1914. He was killed near Ypres in April 1915, around the time Canadians were hit by only the second gas attack in modern warfare.

- A multi-discipline athlete, Percival Molson of Cacouna, Que., had run the 400 metres at the 1904 Olympics in St. Louis before he assembled an infantry unit of former graduates of Montreal’s McGill University to help reinforce the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry. Badly wounded at the Battle of Mount Sorrel in Belgium in June 1916, he returned to action a year later and was killed by a direct hit from a German howitzer near Vimy Ridge in July 1917.

- Four years after taking Canada to the Davis Cup semifinals, Robert Powell of Victoria died leading a 1917 charge at Vimy Ridge two weeks after the Canadian Corps famously captured the strategic high ground. Powell had competed in both singles and doubles tennis at the 1908 London Olympics.

- Rower Geoffrey Taylor of Toronto won two Olympic bronze medals with the four and eight at London and returned to the Games at Stockholm in 1912. Three years later, he fell amid a German gas attack during an advance on Saint-Julien in the Second Battle of Ypres. Taylor’s remains were never found. His name appears on the Menin Gate memorial to the missing.

This is the seventh in an eight-column series on Flanders. Next week: The story of Steve Douglas and his little shop of wartime horrors.

Advertisement