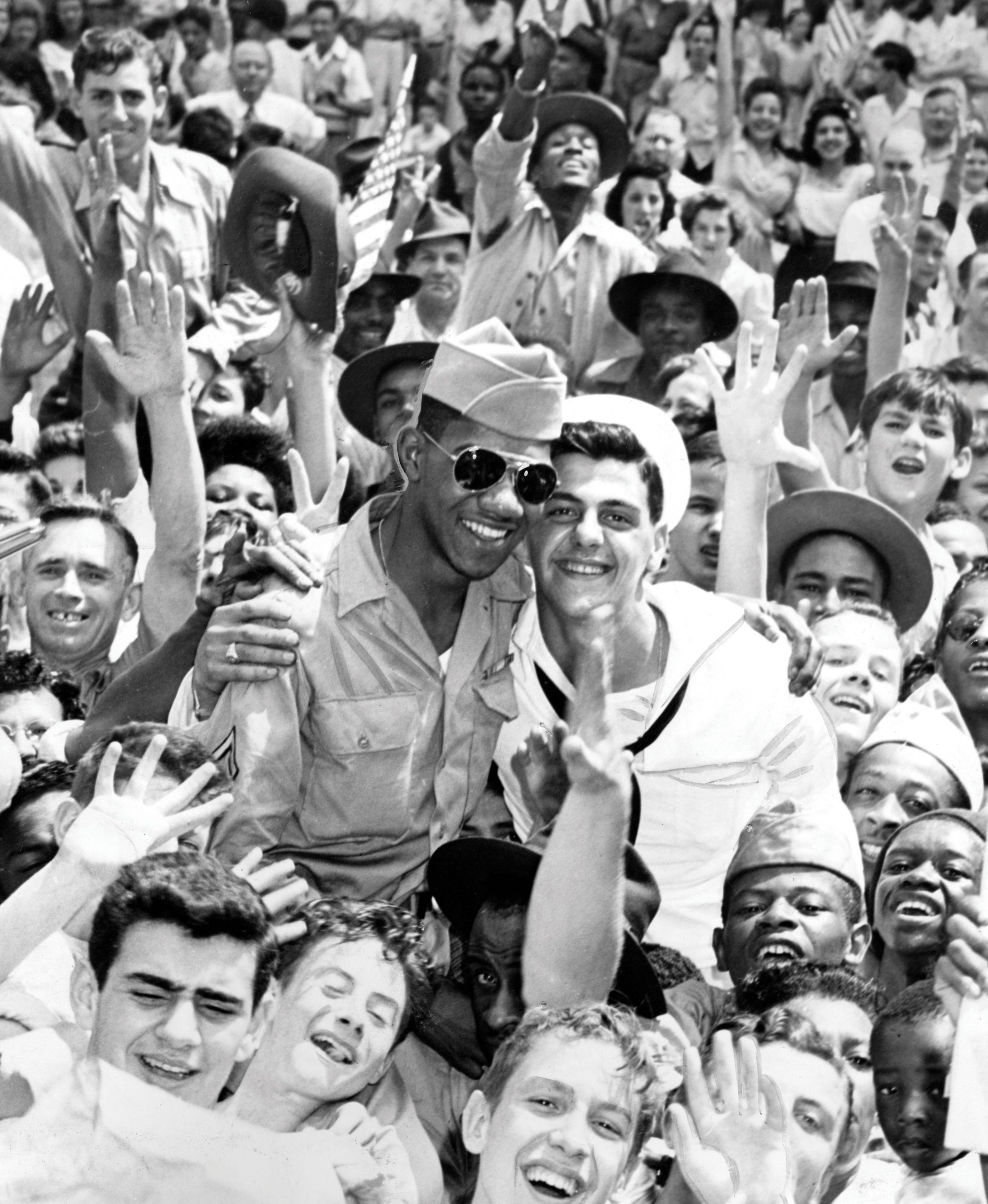

A crowd celebrates VJ-Day (above) by raising a soldier and a sailor on their shoulders in Newark, N.J., on Aug. 18, 1945. [Afro American Newspapers/Gado/Getty Images]

The defeat of Japan brought

horror and joy after

years of conflict

The war was over. The writing had been on the wall ever since American navy pilots gutted the Japanese fleet at Midway on June 4-7, 1942, six months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, sinking four enemy aircraft carriers and turning the tide of conquest in the Pacific.

After a bloody island-hopping campaign that began at Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands in 1942 and worked its way northward, the end came swiftly in a cloud of radioactive dust.

The atomic bombs dropped on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945 marked the dawn of the nuclear age, a harbinger of the fears—and perhaps a lifesaving lesson—that underscored the Cold War in the decades after.

Colonel Lawrence Moore Cosgrave, the Canadian Military Attaché in Australia, signs the Japanese Instrument of Surrender (above) on behalf of Canada aboard the battleship USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on Sept. 2, 1945. [Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images]

The justification for the nuclear attacks remains a topic of debate to this day. For Baylor University history professor Philip Jenkins, however, the matter is “crystal clear, and the moral and ethical issues are straightforward.”

Jenkins acknowledges the bombs were horrific and not to be forgotten. “But let us be clear,” he wrote for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s Religion and Ethics portal in 2016, “In the context of 1945, using the atomic bombs saved lives—millions of them.”

Japanese soldiers relinquish their swords after the surrender. Many opted for suicide. [Military Images/Alamy Stock]

How many millions? Ten million, he said—on all sides. There is no question, Jenkins wrote, that the United States was justified in using the ultimate weapon.

An Allied war correspondent (left) surveys the remains of the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall in Hiroshima, Japan, in September 1945. A month earlier, on Aug. 8, 1945, a uranium-based atomic bomb dropped by the U.S. Air Force B-29 Enola Gay exploded 500 metres directly above this spot. Today, the ruin is the Hiroshima Peace Memorial. [Popperfoto/Getty Images]

Japan’s unconditional surrender five days after Nagasaki was bombed unleashed a wave of relief, celebration and pent-up emotion throughout the Allied nations. Canadian aircrews and paratroopers, who had already celebrated victory in Europe and were now destined to fight again in the Pacific, were stopped in their tracks and granted a new lease on life.

Canadian survivors of the defence of Hong Kong, members of the Royal Rifles of Canada are pictured upon their release from a Japanese prison camp where they worked as slave labourers. Corporal William Tuppert of Quebec City marked himself with an X. Hundreds died; survivors reported years of starvation and abuse at the hands of their Japanese captors. [William Tuppert/Hong Kong Veterans Commemorative Association]

Hundreds of the 1,682 Canadian survivors of the 1941 Battle of Hong Kong, members of the Winnipeg Grenadiers and the Royal Rifles of Canada, did not live to share the triumph with their comrades in arms. They died under brutal conditions in Japanese prison camps. Those who made it had endured years of beatings, hard labour, malnourishment and starvation.

A child in Nagasaki (below) on the morning after the second atomic bomb. [Yosuke Yamahata/Galerie Bilderwelt/Getty Images]

Japanese war criminals were tried and convicted at a series of trials: the International Military Tribunal for the Far East; the Nanjing War Crimes Tribunal; the Manila Tribunal; the Yokohama War Crimes Trials; and the Khabarovsk War Crime Trials over the use of chemical and biological weapons.

Japanese war criminals were tried and convicted at a series of trials.

Within months, Hideki Tojo, former Japanese premier and chief of the Kwantung Army, was executed for war crimes along with six of 24 other top Japanese tried in Tokyo (16 received life sentences). Seven were also found guilty of crimes against humanity, primarily related to their systematic genocide in China. The other tribunals, sitting outside Japan, found some 5,000 Japanese guilty of war crimes; more than 900 were executed.

American military members celebrate the end of the Pacific War—and the end of the Second World War—on the streets of Paris. [Everett Collection Historical/Alamy Stock]

Under American occupation, Japan went on to become an economic powerhouse. But, 75 years later, the war of aggression it waged between 1936 and 1945 is not taught in Japanese schools nor is it widely acknowledged by its leadership or citizens.

Advertisement