Harvey Doane signed on as a 24-year-old lieutenant with No. 10 (Halifax) Siege Battery. He carried this picture of his new bride in a cigarette case throughout his time overseas, calling her “my mascot.” A civil engineer, Doane would go on to nurture a love of the sea for the rest of his life.[Scans by Shoebox Studio Ottawa/Harvey Doane/Album courtesy Mary Doane/Doane Family Archive]

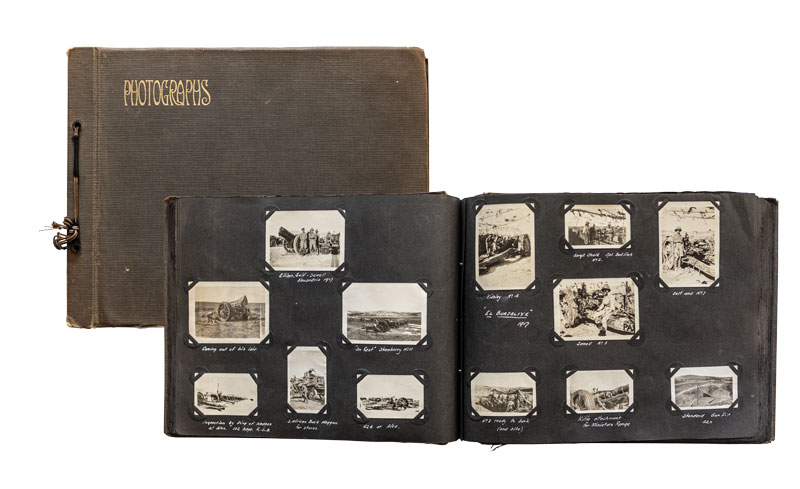

[Scans by Shoebox Studio Ottawa/Harvey Doane/Album courtesy Mary Doane/Doane Family Archive]

I grew up surrounded by veterans of both world wars—my dad was a WW II air force medical officer, my mom a civilian navy decoder tracking convoys out of Sydney, N.S.; my Uncle Ike was a corvette lieutenant on the North Atlantic Run; Uncle Harry and my mom’s cousin-in-law Gordon had been Lancaster pilots; my oldest friend’s father, three doors away, was an army dentist overseas.

Early in my journalism career, I interviewed many First World War vets who, in the early-1980s, were younger and more plentiful than WW II vets are now.

Regardless of the war, they all tended to be reluctant storytellers, preferring not to relive the horrors of the bloodiest conflicts in recorded history. All, that is, except my Great-Uncle Harvey, who commanded a room with his old-world grace, charm and storytelling.

Harvey William Lawrence Doane was a civil engineer who, along with his father Francis (known as FWW, he was the Halifax city engineer) and younger brother William (Billie), had served for years in a militia unit—the 63rd Regiment, Halifax Rifles—before going on active duty with the Canadian Expeditionary Force.

After Billie was killed leading a company charge at the Somme, Harvey—a couple of months shy of his 25th birthday—enlisted as an artillery officer. Harvey and his bride Mildred Whitman were on their honeymoon at the time. He shipped out in March 1917 for England, then Egypt, Palestine and France. Meanwhile, at 49, FWW was by then already serving in the old country.

I remember my great-uncle 50 and 60 years after he returned from the war, a distinctive moustache, his thinning hair combed straight back, wearing a yacht club blazer and holding court, a Scotch in one hand and a loaded cigarette holder between the index and middle fingers of the other.

He and Aunt Mildred, whom he affectionately called “Skinny,” used to come occasionally for Sunday dinner—when the adults, and a somewhat discontented but dutiful little boy, along with whatever wandering older siblings deigned to be home at the time, would gather in the living room for aperitifs.

[Scans by Shoebox Studio Ottawa/Harvey Doane/Album courtesy Mary Doane/Doane Family Archive]

Lieutenant Doane and Major Slater lead No. 10 on parade in Halifax. [Scans by Shoebox Studio Ottawa/Harvey Doane/Album courtesy Mary Doane/Doane Family Archive]

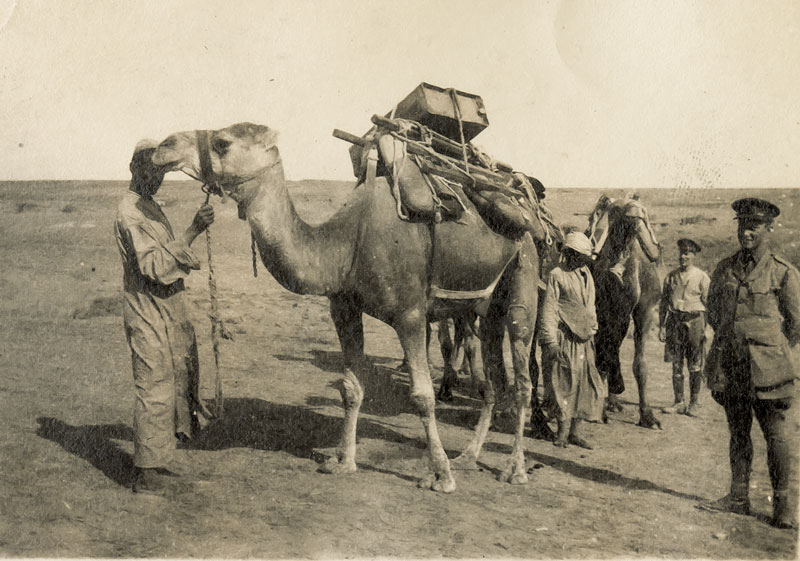

Camels bring water up to 420 Siege Battery, Royal Garrison Artillery, in Gaza in 1917. [Scans by Shoebox Studio Ottawa/Harvey Doane/Album courtesy Mary Doane/Doane Family Archive]

Kids crowd a street in Alexandria, Egypt. Washday at the Doane dugout in Gaza [Scans by Shoebox Studio Ottawa/Harvey Doane/Album courtesy Mary Doane/Doane Family Archive]

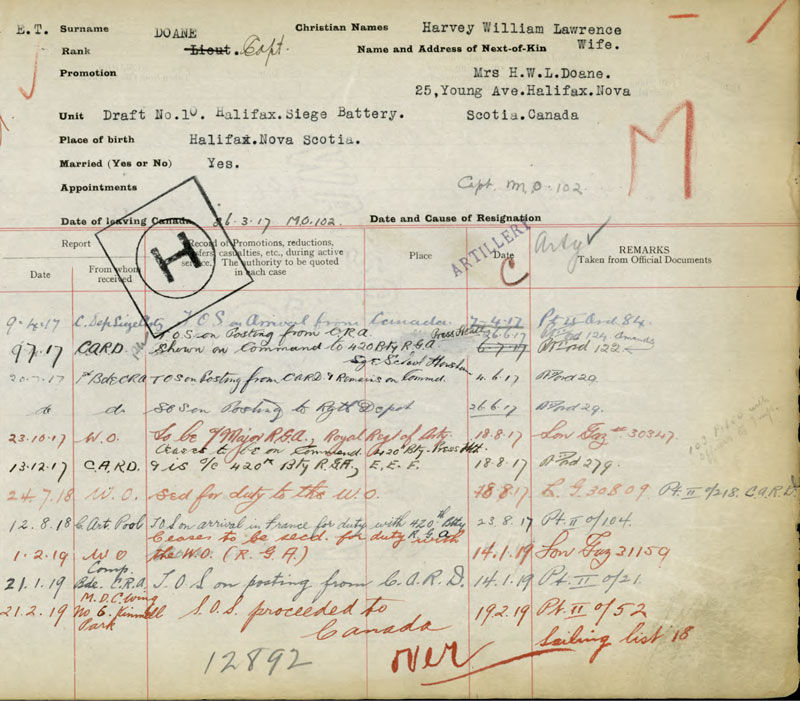

Doane’s service record.[Scans by Shoebox Studio Ottawa/Harvey Doane/Album courtesy Mary Doane/Doane Family Archive]

The stories ratcheted up once the formalities died down 20-30 minutes after the guests arrived and would continue through the meal, which took place in the dining room with my mom’s best linen tablecloth, matching napkins, polished silverware and china plates embellished with the Thorne red rose.

Though Uncle Harvey—his voice, his mannerisms, his sun-baked countenance—is still vivid in my heart and mind, his stories are but vague and distant memories, the tellings to young ears almost as long ago to me now as the war was to him then.

I do remember him relating the tale of some Arab tribesmen, I think they were, who wanted to serve with the British. His commander was reluctant, until one night the locals transplanted the entire contents of his tent, including his bed— with him in it, sleeping soundly. The CO awoke some hours later in the desert, outside camp. The tribesmen were hired.

Two years ago, perusing an “Old Black and White Photographs of Halifax, Nova Scotia” Facebook page, I stumbled upon a picture of my mom with Uncle Harvey and his parents. It had been posted by his granddaughter, Mary Doane, a second- or third-cousin I may have met when we were kids. There was another picture, too, of Harvey and Billie as children, hockey gear in hand, alongside their dad.

And thus began a correspondence, news of family albums filled with photographs, letters and old newspaper clippings, eventually leading to a cover story I wrote for this magazine about Billie (see “Hit so soon,” July/August 2021). But there was so much more in those albums, including Harvey’s photographs from the Middle East and the Western Front. And so, the stories came alive again in pictures.

Uncle Harvey signed on as a lieutenant with No. 10 (Halifax) Siege Battery, CEF, was promoted to captain and transferred to a reserve brigade for three months before he was seconded to a British unit—420 Siege Battery, 102nd Heavy Artillery Group, Royal Garrison Artillery (RGA)—in June 1917. They made him an acting major.

As with so many other weapons of the First World War—machine guns, poison gas, flame-throwers, airplanes—artillery, replacing cannons, was new and deadly effective.

Artillery barrels were rifled, meaning they were machined inside with spiraling grooves that spun their breech-loaded, better-made shells (as opposed to muzzle-loaded cannon balls) like bullets. This made them fly straighter, farther and more accurately. Furthermore, the wheeled weapons themselves tended to be lighter and more mobile than their predecessors.

As British artillery tactics of the day developed, siege batteries were most often employed in destroying or neutralizing enemy artillery and hitting strongpoints, dumps, depots, roads and railways behind enemy lines. A battery would typically include five officers, 177 enlisted ranks, 17 riding horses and 80-some draft horses, along with three two-horse carts and 10 four-horse wagons.

Equipped with 6- and 8-inch howitzers, Harvey’s No. 420 unit would soon be fighting “Johnny Turk”—forces of the Germany-allied Ottoman Empire—in the Middle East. As it turned out, camels—which could carry heavy loads and cover more than 100 kilometres a day without water—came in handy, too. For this, they would have relied largely on the Egyptian Camel Transport Corps—a unit attached to the British army consisting of 170,000 camel drivers and 72,500 camels in some 2,000 companies.

Stretching from Turkey through present-day Syria, Iraq, Palestine and across the sprawling desert of the Arabian peninsula, the Middle East Campaign encompassed the largest territory of any theatre in the war. After British forces twice failed to capture the Ottoman fort at Gaza, General Edmund Allenby took command of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force the same month Harvey and other reinforcements arrived in Egypt. The tide of war in the Middle East was about to change.

Doane’s 420 Siege Battery, Royal Garrison Artillery, (opposite top) gather for a photograph in Alexandria. [Scans by Shoebox Studio Ottawa/Harvey Doane/Album courtesy Mary Doane/Doane Family Archive]

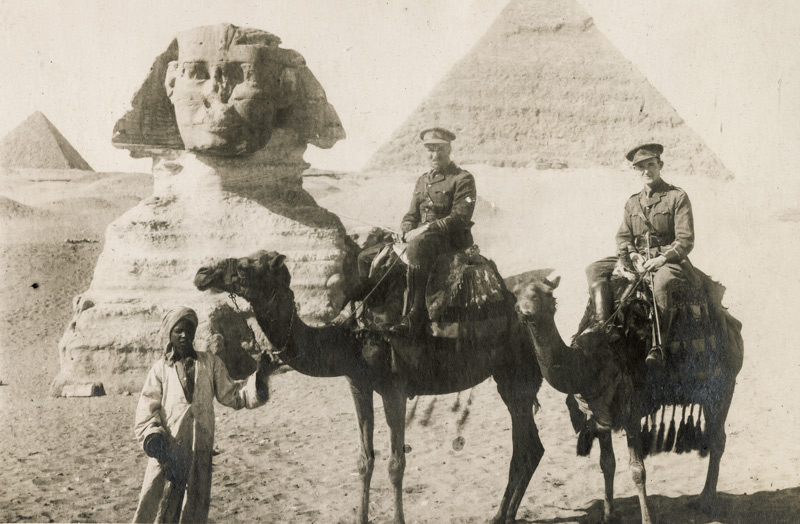

Doane (centre) and a colleague visit the Great Sphinx of Giza.[Scans by Shoebox Studio Ottawa/Harvey Doane/Album courtesy Mary Doane/Doane Family Archive]

Allied Arab fighters enter liberated Jerusalem. [Scans by Shoebox Studio Ottawa/Harvey Doane/Album courtesy Mary Doane/Doane Family Archive]

Harvey’s album traces his journey from training and parades in Halifax to visits with relatives in the old country and unit preparations in central England in the spring and summer of 1917.

Official records of 420’s involvement in the battles of the Middle East Campaign, however, are sparse—the British national archive having apparently not yet digitized that part of the unit’s war diary—but Harvey appears to have been appointed officer commanding the battery soon after it arrived in Egypt in the swelter of mid-summer.

They were in Alexandria by September, living in tents and seeing the sites—Cairo, Luxor, Aswan, Philae. They then moved to dugouts in Gaza, where camel trains brought water and supplies and the 3,000-strong Imperial Camel Corps Brigade helped win key battles during the October-November march to Jerusalem: the Battle of Beersheba, the Third Battle of Gaza, and the Battle of Mughar Ridge.

By year’s end, the Allied advance—aided by an intrepid, brilliant and berobed British army lieutenant named Thomas Edward Lawrence and the Arab Revolt—had crossed the Sinai and entered Palestine. Allenby’s forces captured Jerusalem just before Christmas. Lawrence and his Arab fighters were all the while mounting hit-and-run attacks on supply lines, taking out trains and tying down thousands of Ottoman soldiers in garrisons throughout Palestine, Jordan and Syria.

Harvey walked the newly liberated streets of Jerusalem, photographing the Damascus Gate, the Wailing Wall and the golden Dome of the Rock. There are pictures of the tribal peoples of the peninsula, horse-mounted Arab fighters, a burnt-out tank and a stack of artillery shells—“pills for Johnny Turk.” There’s a camel company formed up in a wadi for battle and images of daily life in desert dugouts and tents, laundry day and camel shearing, the unit telephone exchange and a menagerie of equipment—Caterpillars, cars, carts and artillery pieces of every description—stationary, in action and on the move.

There is also a picture of Allenby himself meeting with Arab leaders.

It was in this December of 1917 that two ships collided in Halifax Harbour—the French cargo vessel Mont-Blanc, laden with high explosives, and the Norwegian ship Imo, carrying relief supplies for Belgium. Mont-Blanc caught fire and exploded, wiping out a large portion of the city in what was then history’s largest artificial explosion. Nearly 2,000 people were killed and 9,000 wounded, many of them blinded by shattered glass.

In the chaotic aftermath, Harvey’s bride Mildred and her sister, my paternal grandmother Katherine, volunteered as nursing assistants at the city’s Camp Hill veterans hospital. They both caught tuberculosis, along with my four-year-old future dad Edward and his two-year-old brother, Arthur.

They were all sent to Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium, a noted TB facility in Saranac Lake, N.Y. My grandmother and Arthur died. My dad lived to 90, despite a lifetime of lung issues. Aunt Mildred saw 87.

Doane’s wife Mildred volunteered as a nursing assistant in Halifax. [Scans by Shoebox Studio Ottawa/Harvey Doane/Album courtesy Mary Doane/Doane Family Archive]

The Middle East Campaign well in hand, the 420th left the Sidi Bishr rest camp in Egypt by train on Feb. 5, 1918, boarded HMT Ixion at Alexandria and set sail for France on March 3. They made port at Marseilles, where the battery unloaded their guns and stores from the ship and put them aboard trains bound for the front, or somewhere close to it. The men followed two weeks later.

Spring 1918 has been described as the most critical period of the war for British and Empire forces. In the weeks before 420 arrived at their position outside Blairville in northern France—10 kilometres southwest of Arras and 50 kilometres northeast of Amiens—the Germans launched a massive attack designed to knock the British out of the war. It was called Operation Michael.

Fighting between March 21 and April 5, 1918, largely in the wasteland left by the 1916 Battle of the Somme, the predominantly British, Empire and French Allied forces would suffer some 250,000 casualties to the Germans’ 240,000.

Operation Michael failed to achieve its objectives and the German advance was reversed during the Second Battle of the Somme in August. The Allied victories would set the stage for the Hundred Days Offensive, spearheaded by troops of the CEF.

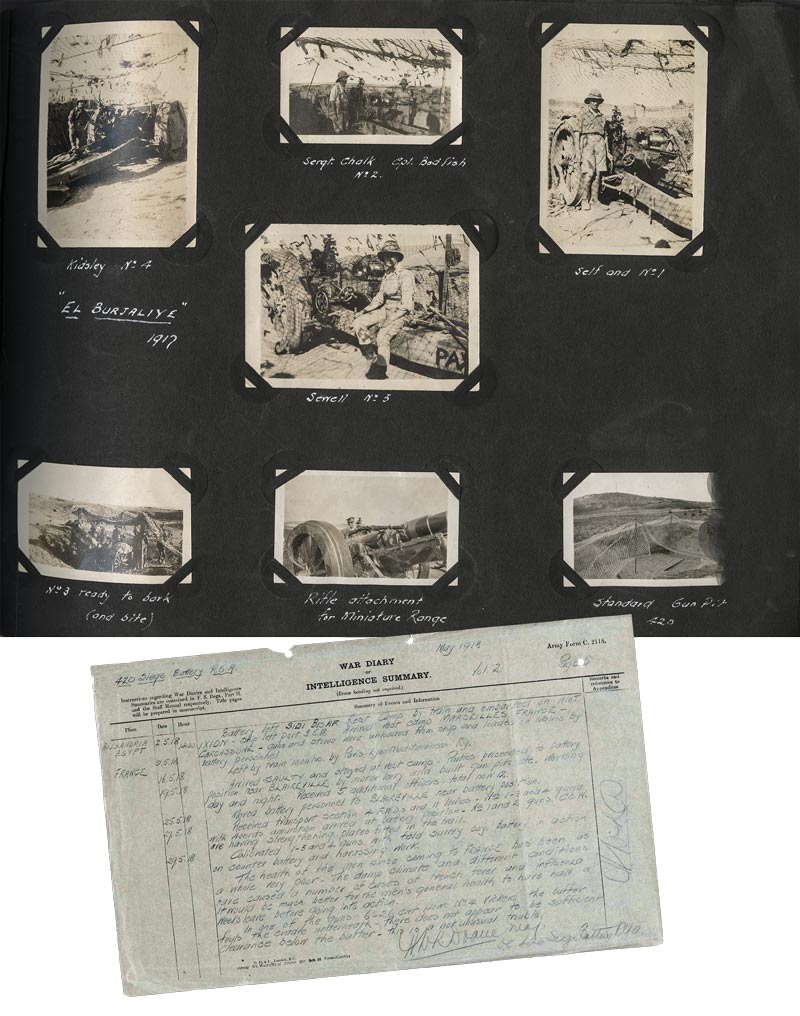

The handwritten unit war diary for May 1918, signed in pencil by “H.W.L. Doane, Maj, OC 420 Siege Battery RGA,” details relentless and exhausting preparatory work for what was to come.

“Parties proceeded to battery position near BLAIRVILLE by motor lorry and built gun pits, etc. Working day and night. Received 5 additional officers—total now 12.”

The single-page document describes logistics and challenges, calibrations and action. “Battery in action on counter battery and harassing work.” Their struggles were not limited to pounding—and taking a pounding from—the German enemy. The transition from a year in the sun-baked deserts of the Middle East to the mud and misery of the Western Front had its own challenges.

“The health of the men since coming to FRANCE has been as a whole very poor,” Harvey wrote on May29. “The damp climate and different conditions have caused a number of cases of trench fever and influenza.

“It would be much better for the men’s general health to have had a week’s leave before going into action.”

Doane’s eight-centimetre-thick album is filled with pictures and notations from Egypt, Gaza, Jerusalem and other parts of the Middle East theatre of war, as well as the Western Front. As 420 commander, Doane went to bat for his exhausted and ill troops, who went from desert swelter to cold and mud in northern France. [Scans by Shoebox Studio Ottawa/Harvey Doane/Album courtesy Mary Doane/ Doane Family Archive]

Doane’s eight-centimetre-thick album is filled with pictures and notations from Egypt, Gaza, Jerusalem and other parts of the Middle East theatre of war, as well as the Western Front. As 420 commander, Doane went to bat for his exhausted and ill troops, who went from desert swelter to cold and mud in northern France. [Scans by Shoebox Studio Ottawa/Harvey Doane/Album courtesy Mary Doane/ Doane Family Archive]

Harvey was transferred to the 123rd Siege Battery, RGA, on Oct. 26, 1918, the day after fighting ended in the Battle of the Selle, in which it was a part. The British unit had served on the Western Front since it was formed in 1916, fighting at Arras, Passchendaele, Cambrai and through the opening victories of the Hundred Days.

Harvey would see them to their triumphant end.

The back half of his album is filled with personal and official photos of France—standing over his brother’s battlefield grave near Courcelette, the handwritten notation below the picture reading “he has given his life for his country so that others might be saved;” rows of captured German guns at Amiens; long lines of German prisoners filing down roads littered with the shattered detritus of war bordered by “beautiful trees of Napoleon’s time,” battered and broken, every one.

He boarded a ship for Canada on Feb. 19, 1919, a 24-day trip. He and Mildred were married 63 years and had three kids. A gifted orator, he gave talks about his time overseas and emceed my first wedding at the yacht club where he was an honorary life member, delivering a devastating series of one-liners.

My brother Ted knew him best. When Ted was 12, Harvey and Mildred took him on a week-long trip to Nova Scotia’s South Shore aboard their 13-metre cruiser Bluefin, which Harvey had converted from a Second World War patrol boat that had plied the Gulf of St. Lawrence on the lookout for U-boats. Harvey ate a raw egg every morning.

“Uncle Harvey was the ultimate gentleman,” said my brother, who fell overboard one morning while making his way forward to mop the dew off the decks. Harvey put the ladder over the side and when Ted climbed back aboard, our great-uncle looked him in the eye and said: “Now there’s a lesson for you—one hand for yourself and one hand for the boat.” He may well have been talking about more than boats.

Uncle Harvey died in 1988, age 96. My daughter Kate—Katherine, named after her great-grandmother—was just seven at the time. We were living in Richmond Hill north of Toronto when her teacher called to say that she was crying because, she had told her, “Uncle Harvey died.”

Kate barely knew him, I thought. But it was her first encounter with death—and, for me, an ultimate appreciation of what an indelible impression Uncle Harvey had made on us all.

Captured German guns at Amiens, France, await their fate.[The National Archives (Britain)]

Advertisement