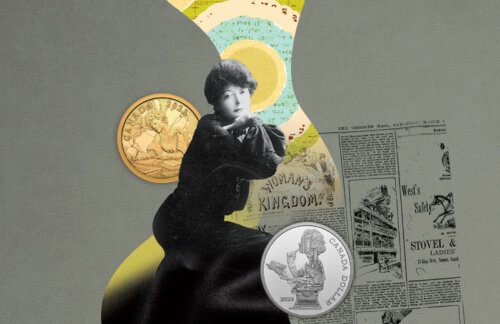

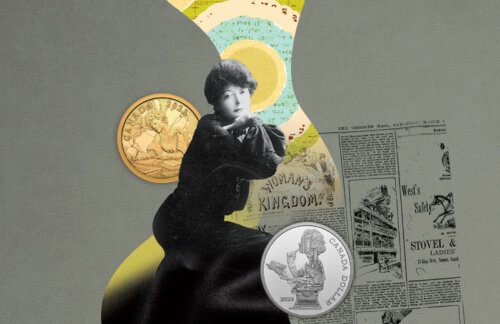

Kit Up – The story of Kathleen (Kit) Coleman, North America’s first female war correspondent

The story of Kathleen (Kit) Coleman, North America’s first female war correspondent

The story of Kathleen (Kit) Coleman, North America’s first female war correspondent

Bruce Stock, a retired major who served with the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (PPCLI) and now lives in London, Ont., shared a tale about a

Recollections of a cherished relative from a First World War scrapbook

Over the years, soldiers have found that music helps pass the time and keeps spirits up on long marches. Some military songs long outlived the

Between the late 1940s and the early 1990s, thousands of Canadians served with NATO in Europe. Early on, there were problems with things as simple

Recently retired Legion Magazine staff writer Sharon Adams has been named the 2022 recipient of the Ross Munro Award for outstanding reporting on Canadian defence matters.

Get the latest stories on military history, veterans issues and Canadian Armed Forces delivered to your inbox. PLUS receive ReaderPerks discounts!

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

Free e-book

An informative primer on Canada’s crucial role in the Normandy landing, June 6, 1944.