The charcoal sketch “Trench Raid” by Harold J. Mowat shows seven Canadians leaving a trench, possibly an advanced listening post, on a nighttime raid.[H.J. Mowat/CWM/19710261-0431]

The attack on German dugouts at Calonne in 1917 was one of Canada’s most successful raids of the war

The war diary of the 21st Battalion (Eastern Ontario) on Jan. 7, 1917, was brief and to the point: “The battalion was relieved by the 19th Battalion in the right subsector this morning…and three companies proceeded to Bully forspecial training. The remainder of the battalion together with a company of the 20th Battalion formed Brigade Support. Casualties nil.”

The battalion’s operation order detailed the personnel of the three companies: two majors, two captains, nine lieutenants, four signallers, 12 stretcher-bearers, 400 selected other ranks, with seven Lewis guns.The next day, the diary indicated the purpose of the special training: a raid on German trenches northeast of Calonne, France.

The aim, as the order stated, was for “the 21st Battalion attacking party [to]enter the enemy trench…for the purpose of inflicting casualties, making prisoners, securing booty and wrecking dugouts in the system of trenches in the area attacked.” A similar raiding party from the 20th Battalion (Central Ontario) was also preparing to assault the German trenches facing them.

This was to be one of the most successful raids ever carried out by the Canadian Corps, a major effort that was to involve 860 soldiers organized into five companies, with careful planning to include hard training, artillery support, deception measures and careful consideration of communications, all occurring under the watchful eye of the corps commander, Lieutenant-General Julian Byng, and the headquarters of the 2nd Canadian Division’s 6th Brigade.

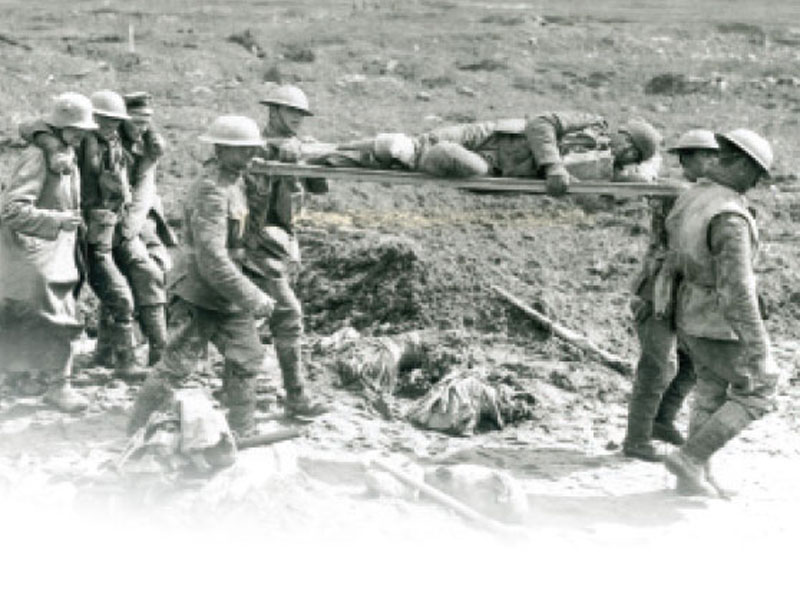

Tired, dirty and wounded, three Canadians (below) return from a July 1917 trench raid at Avion, France. [LAC/CWM/19920085-595]

The attackers blew up more than 40 dugouts.

Trench raids had become a specialty of the Canadian Corps by 1917. The Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, serving with the British 27th Division, launched the first raid by Canadian troops in February 1915, and the Canadian division soon began raids of its own.

Canadian headquarters believed trench raids were good for morale, a way of encouraging an aggressive spirit, securing control of the no man’s land between the trench lines, and relieving the tedium of life in the front line. The division, and the three Canadian divisions that joined it in late 1915 and 1916, became adept at staging raids. Whether the soldiers shared the enthusiasm of headquarters for trench raids was doubtful.

Most of the men likely preferred the unofficial truces that often developed in quiet parts of the front line that stretched from the North Sea to the Swiss border. The raids went on nevertheless, most by small parties of men.

The Lee-Enfield No. 1 Mk III rifle (above) was more robust and reliable than the weapon it replaced, the much-maligned Canadian-made Ross rifle. While the Ross was still used for training in England, all front-line Canadian battalions were using the Lee-Enfield by late 1916. Trench mortars (below) smash barbed wire at Vimy in 1917. [LAC/3194755]

By the beginning of 1917, with planning for the Canadian assault on Vimy Ridge already well underway, raids had increased in number and in size and were often carried out in daylight.

The aim was to get as much information as possible about the enemy and make the Germans fearful, thus affecting their morale and reducing their own patrolling. Even more important, the tactics employed in the larger raids were shaping the template for the forthcoming attack at Vimy.

First came the training. Men detailed for the raid went out on patrols to get the lay of the land they would assault. Engineers at Bully-Grenay, northwest of Vimy and just behind the front, had created a trench system that duplicated the German lines at Calonne and the raiders and their attached sappers had done their rehearsals.

Each platoon formed a separate party: with riflemen (some with wire cutters attached to their Lee-Enfields), bombers, stretcher-bearers and engineers carrying charges and gun cotton to wreck dugouts and machine-gun emplacements. They would constitute the first wave and provide cover for the withdrawal.

The second wave of infantry intended to seize the support line and establish blocks along the communication trenches. It had a Lewis gunner in each platoon. The third wave was to provide carrying parties and technical support. Machine guns and artillery were positioned on the flanks of the raid to minimize the German response.

Each soldier carried a rifle and bayonet, 100 rounds of ammunition, 10 bombs, a sandbag, a water bottle and a haversack. Each company had six men carrying 10 rifle grenades, and the companies had canvas to throw over the enemy wire if necessary.

Signallers lugged telephone wire to establish contact between the raiders and headquarters. Engineers, the most heavily laden, had ladders to bridge trenches or carry wounded. There were also smoke bombs and mortar bombs adapted to be thrown into dugouts. The rehearsals and the careful preparation satisfied Byng that the raiders were ready.

Aggressive patrolling scouted the enemy’s barbed wire entanglements and the 2nd Division’s artillery was tasked to destroy it. Too often, attackers got hung up on the rows of wire and were shot by the defenders. Patrols on Jan. 16 confirmed the wire was largely destroyed.

By this stage of the war, the Germans ordinarily ranged their defences in depth with few men in the trenches and most of their troops in well-constructed dugouts in the support line. Their machine guns supported each other with fixed arcs of fire, their officers could call on mortars and artillery for support, and they anticipated that attackers who broke through the lightly defended front line would then be smashed by rapid counterattacks.

But the Canadians were fully aware of the German tactics. They had pinpointed most of the enemy machine guns and dugouts and planned to hit them with artillery. The infantry and sappers were to take out strongpoints one by one with bombs. There were to be no more futile frontal assaults with their inevitable heavy casualties, and the raiders’ intent now was to create gaps through which the infantry could move forward.

Starting at dawn on Jan. 17, the companies from Bully took up positions at the front. At 7:45, the artillery opened fire and the first wave moved to the assault, followed at 50-metre intervals by the next two waves.

The Germans, into their morning stand- down, were carrying out routine tasks when their lines were pummelled by Canadian gunfire. At the same time, two battalions on the left flank staged diversionary attacks and the gunners laid down smoke in front of the raiders.

Fifteen minutes after zero hour, British tunnellers exploded a mine to the north, further distracting the enemy. Within five minutes, the first wave reached the German wire and easily breached it, thanks to the artillery preparation.

Canadian troops, in this instance armed with American manufactured P14 rifles, mount a demonstration in England in 1917. [LAC/PA-004810]

Details of the raid were described in the history of the 20th Battalion:

We discovered five sentry groups in the front line, which were quickly killed or captured. The line was lightly held. Numerous dugouts were examined, most of which were unoccupied and full of water, and in only two of them did we take prisoners. Very wide at the top—almost impossible to jump—the trench had fallen in at many points and was badly damaged by shellfire….

The second wave passed over the German front line shortly after the first reached it. Some of us bombed our way up the communication trenches, in which a number of dugouts were found and bombed; others went overland, the wire between the first and second lines being too badly cut to form a serious obstacle.

We succeeded in advancing to the line of the second barrage, which was on the support line, some minutes before it lifted. At twenty-four minutes past “zero” we had entered the support line and final objective; the artillery having lifted to a protective barrage.

In the support line we found two trench mortar emplacements, both totally destroyed by our artillery fire, and a machine-gun emplacement demolished….

The dugouts here were more numerous, and their occupants extremely unwilling to leave them; as time did not allow much persuasion, mobile charges were thrown in and dugouts and men annihilated together….

The engineers, who carried the mobile charges, were enjoying themselves. One of them was asked how he was getting on. “Fine!” he replied. “You come to a dugout—light the fuse—drop the charge in—run like hell—look over your shoulder and see the dugout come out of the door.”

Headquarters believed trench raids were good for morale.

Stretcher-bearers and German prisoners bring in wounded during the Battle of Vimy Ridge in April 1917. Push daggers, like this Robbins of Dudley example, were used in hand-to-hand combat. They were privately bought by men looking for that little something extra during trench raids. [CWM/20060208-001]

By 8:40, the 20th’s raiders returned to their lines with no man left behind. As for the 21st Battalion, three German prisoners were sent back at 7:55, and two minutes later the major in command of the 21st’s raiders said he was at the German front line, that all was well, and that two men had been wounded by the supporting gunfire. Enemy retaliation was said to be slight.

By 8:12, all the 21st’s raiding parties but one had reached their objectives on the enemy support line, and soon enemy artillery and mortar fire began to increase, as did Canadian casualties. The withdrawal began at 8:30 and enemy retaliation was “almost nil.”

But that did not last long. The German artillery started firing at the battalion’s front line. The withdrawal continued, well covered by the Canadian artillery. Just after nine o’clock, the raid ended and the German retaliation ceased.

The Calonne trench raid was a success. The attackers blew up more than 40 dugouts, exploded three ammunition dumps, captured two machine guns and two trench mortars and destroyed more.

More than 100 prisoners were taken by the raiding parties and many of the enemy were killed, including unknown numbers in the dugouts destroyed by the sappers and infantry. The Germans later claimed that their losses were 18 dead, 51 wounded and 61 missing, figures that had certainly been heavily massaged. The Canadian losses, however, were serious, with 40 killed, 135 wounded and three missing. One raiding company of the 21st lost almost a quarter of its men killed or wounded.

A detailed study of the Calonne raid by historian Andrew Godefroy argued persuasively that the knowledge and experience gained from raiding had moved beyond simply harassing the enemy; by 1917, it had become on-the-job training. And combined-arms warfare, as employed during the raid, was on the way to becoming the new Canadian doctrine. This doctrine was unquestionably the foundation of the Canadian Corps’ later successes at Vimy in April 1917 and in the Hundred Days of 1918.

Were trench raids productive?

Generals liked raids on the enemy. They raised the troops’ morale, they said, and they kept the enemy fearful of sudden death. But trench raids also invited retaliation—the Canadians and the Germans were both good at the tactic—and produced casualties on both sides.

German trenches demolished by artillery in July 1916.[Henry Edward Knobel/LAC/3520934]

When well planned, as at Calonne, a large raiding party could take many prisoners and cause real damage to enemy dugouts. But the raid at Calonne also left 175 Canadians dead and wounded, and they were seasoned soldiers.

Poorly planned raids could be even more costly. On March 1, 1917, the 4th Canadian Division launched a raid at Vimy with some 1,700 men and suffered a 40 per cent casualty rate—so many that the Germans offered a truce to recover the bodies. This bungled raid may have harmed the division’s later effectiveness.

Sensible commanders like General Arthur Currie supported raids that had a genuine purpose, but he looked at others—raids designed solely for the purpose of raiding—as the vanity projects of senior officers. Lieutenant-General Julian Byng, however, was a true believer in raiding, and Currie said they had their one heated discussion on this subject. Currie’s doubts made sense, but the merits of trench raids remain open to argument.

Advertisement