Soldiers with the 22nd Battalion (French Canadian) repair a damaged trench in July 1916. Trench warfare combined long periods of tedious labour broken by deadly attacks. [DND/LAC/PA-000253]

The Great War took more than 600,000 Canadians from all parts of the country and put them in uniform. The transition from civilian to soldier was not easy, and everyone had to learn much about military procedures and culture—uniforms, ranks, insignia, rations, weaponry, terminology—and, most important, adjust to the presence of aggression, violence and death.

Amid all this, the workaday world of soldiers at or near the front was, at times, a monotonous routine broken, thankfully, by letters from home, packages of foodstuffs, socks or tobacco, and dark humour. Uniforms and gear had irritating foibles. Meals were basic, dull and often cold. A glossary of slang—booby trap, crump, napoo—unique to the trenches evolved. Even after the war ended and most soldiers became civilians again, some linguistic quirks—basket case, shell shock, strafe—followed them home and endure today. Here is a brief look at what our fighting men wore, said and ate.

(Left) Maconochie rations gave troops flatulence, according to at least one soldier: “We marched along on air released by hundreds of men breaking wind.” (Right) Sturdy but light mess tins were used to prepare and heat food and as a container from which to eat and drink. This one belonged to Capt. T.D. Cumberland, a medical officer with the Royal Army Medical Corps. [Wikimedia; CWM/20100106-047]

Putting on the uniform was the first stage in becoming a soldier, the one that every recruit shared. Gathered at the Valcartier military training camp in Quebec in August and September of 1914, many of the men of the first contingent waited for uniforms to arrive. Hurriedly made by contractors chosen by Minister of Militia Sam Hughes, the uniforms had their flaws.

The boots seemed to be made of paper. Most would fall apart in England’s wet weather and have to be replaced. A challenge for every new soldier was properly putting on the nine-foot-long protective woollen wraps known as puttees, which were designed to keep water, mud and stones out of the boots. The load-bearing equipment—designed by J.W. Oliver, a Canadian surgeon who served with the British Army in the Red River Expedition of 1870—was an awkward, uncomfortable jumble of belts and pouches. British webbing soon replaced it.

A steel combat helmet, also known as a shrapnel helmet, tin hat, dishpan hat, washbasin, battle bowler, Tommy helmet and Brodie helmet (for its designer). German soldiers called it a Salatschüssel (salad bowl). [CWM/19720102-056a]

The service dress caps and khaki wool jackets (with brass buttons to shine) and pants were adequate, but British pattern service dress jackets began to replace the Canadian issue as the months passed. Under the jacket, men wore a grey collarless shirt that buttoned halfway down the front. They also received a greatcoat and two grey army blankets, plus a straight razor, mess tins and a cap comforter (a knitted scarf that rolled up into a cap).

Officers purchased their own uniforms, tailored and made of better material than soldier’s serge. They could also sport a waterproof trench coat or a fleece-lined “British Warm” overcoat. The polished-leather Sam Browne equipment—belt, straps, holster, etc.—was not usually worn in the field (nor were swords carried!), but officers wore a shirt and tie under their jacket. Sensible officers realized that German snipers knew who to shoot at first, and many began to carry a rifle and wear a modified soldier’s uniform.

Canadian mounted troops in standard-issue uniforms—cap, jacket, pantaloons, puttees, leather leggings and boots—at Camp Valcartier in Quebec in 1914. [Andrew Merrilees/LAC/MIKAN 4473746]

Weapons assigned to Canadians at the start of the war were less than perfect. The soldiers received the Ross rifle, a fine target-shooting weapon but one that jammed in field conditions. Over Hughes’ objections, the Lee-Enfield rifle replaced it. Canadian artillery was also largely obsolete, and the Colt machine guns hurriedly purchased from the United States were not included in the British inventory; all would be superseded.

The Canadian Corps very soon had much of the same equipment and dress as other formations in the British Expeditionary Force. All that marked them out as Canadian were their cap badges and shoulder flashes, and after bowl-shaped steel helmets came into use on the battlefield in 1916, neither badges nor flashes were much in sight. The uniforms remained, but leather jerkins and sheepskins were common in cold weather. In the filth of the trenches, of course, everything was grimy all the time.

A .303-calibre Savage-Lewis aircraft gun that belonged to Canadian flying ace Billy Bishop. [CWM/19700026-001]

In battle, the soldiers’ load was immense. The rifle, bayonet and rounds of ammunition were heavy, and some soldiers had to carry the Lewis light machine gun, ammunition drums, grenades and flares. The ammunition was necessary to repel enemy counterattacks when objectives were seized. Each man also carried a respirator, iron rations (a tin box with preserved meat, meat extract, cheese, biscuit, tea, sugar and salt), mess tins, personal items, a water bottle, two empty sandbags and a groundsheet. Many also carried a shovel, pick or wire cutters. The whole kit could weigh as much as 65 pounds. How men could move quickly and fight after lugging such a load was remarkable.

Soldiers also had to learn a new language when they joined up. There were the ranks to master, of course: officers, from cadet to field marshal, and other ranks, from private to warrant officer. The ORs (other ranks) were led by NCOs (non-commissioned officers) who, along with one-pip wonders (second lieutenants), enforced discipline in their platoons, using the KRs (King’s Regulations) to mete out punishments such as CB (confined to barracks).

Then there was the army’s phonetic alphabet to master: ack-ack (for anti-aircraft artillery) was A and A; machine guns were emma gees or MGs; and time after noon was pip emma, from pip (P) and emma (M) in air force signalese. There were also specific army terms, including a pull-through (wire gauze on a cord used to clean a rifle bore) and a housewife (a sewing kit). Spare clothes and boots were kept in a kit bag, into which a soldier’s troubles were sometimes packed.

Soldiers collect pieces of kit left behind on the battlefield. Aside from weapons, essentials included gas masks, haversacks and canteens. [DND/LAC/PA-001044]

With so many British-born men in Canada’s military, a host of slang terms—many brought from India by the British Army—quickly became part of the Canadians’ vocabulary. A blighty was a non-life-threatening wound that got a soldier sent to convalesce in England. Blighty also referred to England itself. That hospital stay could be cushy (very comfortable). Cooties (lice) were never cushy. Soldiers learned quickly that they needed a chit (voucher) to get anything from the QM (quartermaster) and to beware of anyone in a trench coat (a military style double-breasted raincoat) because he was an officer and maybe even a brass hat (high-ranking officer) with red tabs (gilt-embroidered red patches worn on uniform collars). Of course, everyone wore khaki, another Indian Army term.

A battlefield kit. [W.E. Storey Collection]

Soldiers were Tommies (British) or Canucks (Canadians), and men of the Canadian Corps sometimes called themselves the Byng Boys (after their popular commander, Lieutenant-General Sir Julian Byng).

Then there were the Boche, Hun, Fritz or Jerries, all terms describing the Germans, whose weapons included potato mashers (grenades), rum jars (mortar shells), crumps (shells that exploded with a distinctive c-r-r-r-ump sound), whiz bangs (small-calibre high-velocity shells), and Big Berthas (420mm German howitzers).

German gunners were usually alert when Canadians went over the top (leaving the trench) in an attack that started at zero hour. A close call could get a man’s wind up (instill fear) and give him cold feet (yielding to that fear), and some soldiers suffered from shell shock (psychological disturbance caused by prolonged exposure to bombardment). When soldiers were killed, they bought the farm, were knocked out, were pushing up daisies, their number was up, or they went west.

The Spanish flu (the influenza pandemic) infected tens of thousands in the CEF, but so did trench fever (rickettsia), caused by those wretched cooties, and trench foot (from standing on wet, cold, unsanitary ground and characterized by numbness, tissue turning red or blue, decay, swelling, blisters, open sores, fungal infection and gangrene).

There was endless talk of women, and then there was cursing. Perhaps the most frequently used term was fuck, being employed as an adjective, noun, adverb and every other grammatical variant. If someone had nothing, all he had was sweet fuck all. (English soldiers in France also more politely expressed this as napoo [il n’y a plus/there’s no more].) And shit, piss, bloody, balls and bugger were frequently combined in creative ways. Senior officers and padres (ministers and priests) sometimes launched crusades to civilize soldiers’ speech, but these never worked any better than attempts to get them to swear off alcohol.

Trench foot—from standing on muddy, unsanitary, cold ground—was curbed by applying whale oil, pairing up soldiers to inspect each other’s feet, and using wooden duckboards. [LAC/PA-149311]

Many Canadians spent time in Belgium, not least at Wipers (Ypres). There was the village of Plug Street (Ploegsteert) and in Poperinghe there was Toc H (an all-ranks soldiers’ club called Talbot House and rendered in signaller’s code—Toc for T and H for H).

Most of these words and expressions were used by all who served in the British Army, and there seem to have been few original Canadian terms. Even francophone soldiers picked up the terminology, sprink-ling Anglo curses and terms into their joual and frequently blasphemous swearing. Some observers thought Canadians cursed more than other soldiers, but this was likely apocryphal. What was clear was that knowing and speaking the army’s language was part of the process of turning civvies (civilians) into soldiers.

Canada was no gourmet paradise in 1914. Most working men and their families ate a diet heavy on bread, tea, cheap cuts of meat, potatoes, sugar, cheese and jam. Fresh vegetables and fruit were unavailable except in summer and canned meats and vegetables were staples. The British diet was similar—and the Canadian Corps’ food overseas came from Britain.

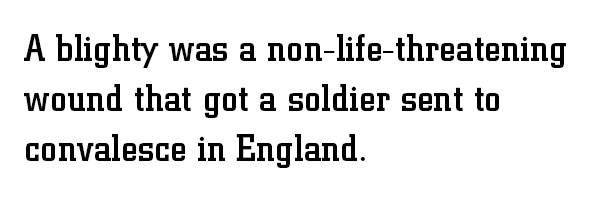

The British Army’s standards for feeding soldiers were laid down in 1914. The aim was to provide 4,300 calories a day, a recognition that soldiering was hard work. If this was the intent, it was not often achieved, and certainly not at the front. Each day each man was to receive:

Rations were brought forward from supply dumps and distributed to units, which in turn broke down the food by companies and platoons. Soldiers heated up their food on Tommy cookers (camp stoves with solidified alcohol fuel). When out of the line, battalion cooks, some untrained, prepared hot food; occasionally, in quiet periods, stew could reach the front trenches in insulated containers.

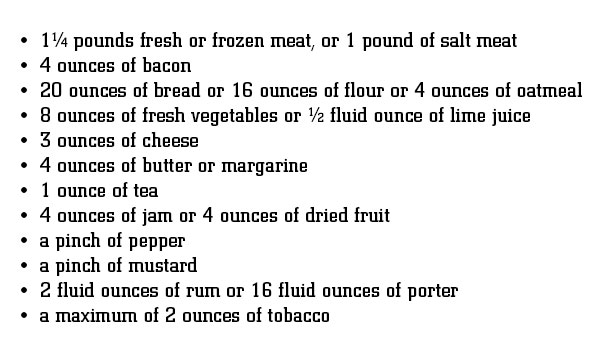

Too often there was no fresh bread. As the war went on and U-boats sank merchant ships carrying grains and other food from North America, the quality of bread deteriorated dramatically. Stone-hard biscuits were often all that was available. There was rarely any fresh meat; instead tinned bully beef from Canada, the U.S. or Argentina was the norm, notorious for being all fat and gristle. Worse still was M&V (meat and vegetables) and Maconochie, tinned stew of turnips, carrots and potatoes named for its manufacturer in Aberdeen, Scotland. This was barely tolerable when heated over a brazier at the front and fat-laden swill when it had to be eaten cold. Bacon, cooked at the front by individual soldiers, was a rare treat. Jam was made from plums and apples, while tea and condensed milk with sugar was the normal beverage. Water was brought up in petrol tins and frequently tasted foul; as a result, soldiers often drank from ponds and streams. During action when rations could not reach the front, soldiers made do with iron rations—bully beef, hard biscuits, tea and a canteen of water.

Mealtime in the trench. [H.E. Knobel/DND/LAC/PA-000157]

The army, conscious of the need to reduce the strain on shipping, made efforts to supplement rations. The Canadian Corps instructed its divisions to operate farms in France, and substantial efforts were made. In 1918, the 16th Battalion harvested 278 tons of potatoes and tons of cabbages, turnips, carrots and beets, the work being done by men who were deemed unfit for the trenches. And soldiers, of course, supplemented their rations, buying (or frequently stealing) food from French and Belgian farmers or visiting estaminets, makeshift taverns in rear areas where they could buy eggs and chips and cheap beer or wine. Service organizations such as the Sally Ann (Salvation Army) also ran canteens where men could get a cup of tea and some hot soup and paper to write a letter.

Parcels from home supplemented the rations. Mothers sent cookies and cakes that, even if they arrived stale or mouldy, were shared out and eagerly consumed. Other much-desired items included candy, canned salmon and tinned fruit in sugary syrup. Given the lag time in mail arriving from Canada, sometimes three or four parcels arrived at once, making for a feast. Whatever the sources of food, one study found, surprisingly, that soldiers gained an average of six pounds during their military service.

More than 3 million tons of food—most of it canned or dry—was shipped from Britain to troops in trenches, including corned beef (left), bread and biscuits. Tin cans (right) could be made into improvised bombs. [Waxworks Encaustic Supplies]

To no one’s surprise, officers ate better than their men. Each officer had a batman who looked after his kit, clothes and cooking. The batman would make tea and fry bacon and occasionally an egg for his officer. Out of the line, officers ate together, each contributing francs toward the “extra messing” that included a few luxuries. In August 1918, days before the advance to the Drocourt-Quéant Line in France, Lieutenant Ivan Maharg was the 1st Canadian Mounted Rifles’ mess president, and one of his jobs was to try to find some fresh meat. He wrote home that he gave the mess sergeant 20 francs “to see if he can’t find us some eats in this village. I doubt if he can,” he added, “there’s not much here.”

Cigarettes and rum (in gallon jars marked SRD, for Supply Reserve Depot or, informally, Service Rum Diluted, Sergeants Rarely Deliver or Soon Runs Dry) were morale boosters. [CWM/19740414-003/CWM/20040092-001]

Unlike the ORs, officers could get liquor. The regular soldiers, however, were limited to a daily two-ounce shot of rum—unless the senior officer was a teetotaller, as some were, and substituted soup.

“When the front is altogether a beastly place,” wrote one infantryman, “we have one consolation. It comes in gallon jars.” The army rum ration—adopted from established navy tradition—became a ritual of the war. Rum was doled out by an NCO and had to be drunk in his presence, not hoarded. Before an attack, there might be an extra tot. “We always get a drink of rum before we start anything,” wrote Private Hilaire Dennis after fighting on the advance to the Drocourt-Quéant Line, “and then we can go through fire or do anything.” After the action was over, the survivors might get their platoon’s full allocation despite the dead and wounded no longer needing their ration.

Members of the Royal Highlanders of Canada chow down on battlefield rations. [Legion Magazine archives/000127]

Advertisement