Major Charles Comfort depicted Canadian soldiers as they began the ill-fated Dieppe Raid on Aug. 19, 1942, in this postwar painting. [Maj. Charles Comfort/CWM/19710261-2183]

Remembering the courage and fortitude of the Canadian forces that mounted the ultimately ruinous raid

John Goheen has a tradition. When the tour guide on The Royal Canadian Legion’s biennial Pilgrimage of Remembrance to battlefields and war cemeteries in France, Belgium and the Netherlands gets his groups to the French coastal town of Dieppe, he rouses the willing to meet on the stony beach at 5 a.m.

Once the early risers are gathered, he pours everyone a drink of the local Calvados brandy or scotch. Then at precisely 5:20, they raise their glasses and toast, “To the men of Dieppe!”

It was at that time on Aug. 19, 1942, during the Second World War that some 6,100 Allied troops—nearly 4,963 Canadians among them—landed in a daring raid that quickly turned into a disaster.

The tour typically reaches Dieppe in early July. By then the morning light allows the pilgrims to clearly see the menacing cliffs that surround the beach, as well as the concrete fortifications where the German occupiers dug in to face the attack. A 12th-century castle rests on top of one cliff, its ancient defences reinforced for 20th-century warfare. It’s not unusual for one of the pilgrims to remark of the raid: “What were they thinking?”

The truth is that a lot of thought went into the daring assault.

The idea began with Britain’s Combined Operations Headquarters, headed by the charismatic Vice-Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten. The unit was established to co-ordinate army, navy and air force units on a series of raids designed to keep the enemy distracted while the Allies gathered enough combined American and Commonwealth forces for a larger invasion of the continent.

The U.S. had come into the war in December 1941. It was anxious to strike at Germany, but had not yet fully established its military might. The planners knew that when they did storm the continent, it would have to begin with an amphibious attack. Part of the mandate of Combined Operations was to build and test new equipment and methods for mounting such a siege. For Dieppe, Mountbatten and his team wanted to plan a raid that was larger than anything the Allies had tried before.

The plan was to capture a French harbour and hold it for a day while causing damage, taking prisoners and grabbing any intelligence, code books or plans they could find, then depart before the Germans could send reinforcements.

The view from the top of a cliff near Dieppe gives a sense of the geography [Lieut. Ken Bell/LAC/3524440].

Eventually, Dieppe, a coastal town about 200 kilometres southwest of Calais, was picked and the planning began for Operation Rutter, which was scheduled for early July. Lieutenant-General Bernard Montgomery, head of South Eastern Command in Britain, was one of the mission’s key planners.

The plan was to land on the beach with the new Churchill tanks. Batteries on the surrounding cliffs would have to be captured during the night before so they would be neutralized by the time the attackers came ashore. When the Americans joined the Allies, German leader Adolf Hitler was convinced they would try to invade the continent. He had already started to build his “Atlantic Wall,” an attempt to strengthen fortifications along the coast from Norway to the Spanish border. Hitler wanted to ensure that if the Allies attacked, the Axis forces could not only halt them, but drive them back into the sea.

What Allied planners didn’t know was that the Germans had already built an elaborate series of caves and other hidden fortifications to fend off an assault.

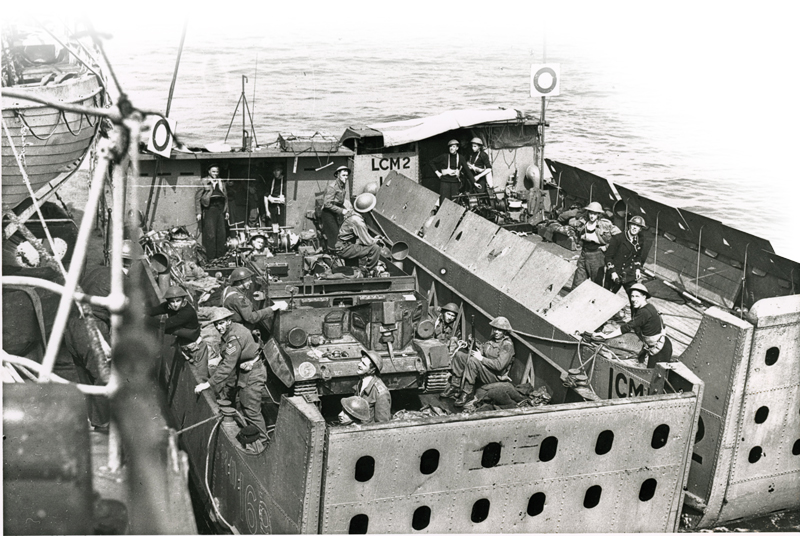

Canadian soldiers aboard landing craft encountered as they launched the attack. [LAC/3396538]

While this was being planned, politicians in Britain and Canada were getting anxious about when the army was finally going to fight. Many Canadians had been in Britain for two years and were itching to see action. Soviet leader Josef Stalin had demanded the Allies open a Western Front to take the pressure off his forces who were desperately defending their own country in the east.

Canadian Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King wanted to show Canada doing its part in the war, but was wary of too many casualties. Meanwhile, his Defence Minister James Ralston was eager for Canadians to get into battle. Lieutenant-General Harry Crerar, commanding the Canadian Army in Britain and filling in for General Andrew McNaughton on sick leave, had heard rumours of the Dieppe plan and demanded Canadians be used for the raid.

Eventually, the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division under Major-General John Hamilton (Ham) Roberts was called on for the mission. The men had already been loaded into their ships in ports across southern England when, after much delay, Operation Rutter was cancelled due to bad weather.

There was much disappointment among the Canadians. They had been well trained for their specific tasks and were in top-notch physical condition.

Once on board, they were told this would be no drill.

It was back to the drawing board for Combined Operations. But before a new plan was developed, a staffer suggested simply remounting the Rutter plan in August. At the time of the suggestion, Montgomery had left the scene, having been selected to lead the campaign in North Africa. So, Mountbatten took the plan to the British Chiefs of Staff Committee, arguing that, while the enemy might have known that a large raid was planned, there was no evidence that they knew where.

“If by some unsuspected chance they stumbled upon Dieppe as our target, they would never for a moment think we should be so idiotic as to remount the operation on the same target,” he argued. As historian Mark Zuehlke noted in his book, Tragedy at Dieppe, “The circular logic yielded the desired result.” The Canadians went back to training exercises from the original plan.

Hitler wanted to ensure that if the Allies attacked, the Axis forces could drive them back into the sea.

Major-General John Roberts oversaw the raid. [Lawren Harris/CWM/19710261-3102]

On the night of Aug. 18, nearly 5,000 men from the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division and 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade, along with some 1,000 British commandos and 50 U.S. Army Rangers, were loaded onto ships. Once on board, they were told this would be no drill. There were more than 250 naval vessels and 74 air squadrons supporting them.

The main assault would be in front of the former casino on the beaches code-named Red and White. Flanking forces were to land earlier on adjacent banks to the east and west of Dieppe at Puys (Blue Beach), and at Pourville (Green Beach). British commandos were to neutralize coastal batteries capable of shelling the beaches from farther away.

The Royal Hamilton Light Infantry was to lead the assault on White Beach to the west, while the Essex Scottish Regiment would lead the way on Red Beach. Both fronts would be supported by the 14th Army Tank Regiment (The Calgary Regiment (Tank)).The South Saskatchewan Regiment and Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada were to land off Green Beach, while the Royal Regiment of Canada and three platoons of The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada were set to hit Blue Beach.

There was to be no aerial bombing before the invasion to keep the element of surprise and to avoid creating obstacles from damaged landmarks that might make manoeuvring tanks difficult.

From the start, it all went wrong.

First, the attacking force ran into a German supply convoy on its way to Rouen, France, and a firefight broke out. This alerted the coastal defences to enemy action.

Then the advance parties arrived 35 minutes late at Blue Beach and were quickly pinned down on the waterfront. The Green Beach attackers were on time, but about half the group was put down off their target and lost time getting to their allotted place.

Overhead, the air forces kept up a lively battle with the already weakened Luftwaffe. When the troops caught their first sight of the town of Dieppe, however, they were shocked to see it relatively undamaged. The heavy bombardment called for in the Rutter plan had been replaced by strafing of beach defences by Hurricane fighters moments after the troops landed.

By the time the main force hit the beaches directly in front of the town at 5:20, the element of surprise had been lost. Accurate rifle, machine-gun and mortar fire rained down on the soldiers as landing craft came ashore.

Some men were downed in the water, while those who made it to the beach had to run on chert—very hard, fist-sized stones that had been rounded by the tidal action—that slipped under their feet. This was far different from the sand beaches the troops had practised on in Britain.

Those on shore were then hampered by a delay in the arrival of tanks.

Churchill tanks from The Calgary Regiment had been specially waterproofed so that, after disembarking from landing craft, they could navigate shallow water before charging ashore. Unfortunately, some exited the vessels too soon and sank. Tanks that made it ashore, meanwhile, had their tracks clogged by the chert. And the seawall also turned out to be a formidable obstacle. Only a handful of tanks successfully reached the esplanade in front of the beach.

To the west end of Dieppe on White Beach, the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry succeeded in getting through the barbed-wire barriers that defended the shoreline and cleared the old casino that was being used as a fortification.

Throughout the chaos, communications back to Roberts’ headquarters aboard HMS Calpe were in a shambles. Most of the wireless sets were damaged in the fighting or in the sea water. Roberts was trying to understand what was going on. In addition to the faulty messages he was receiving, the Germans were sending out false communications, confusing things even more. The battle was already a lost cause when Roberts, having received a garbled message that he took to understand as some success on the beach, ordered his reserve force, the Fusiliers Mont-Royal, to go into action in support. It was an order that, even today, remains controversial.

Of the nearly 5,000 soldiers who had embarked on the raid, only 2,210 came back with the retreating forces.

Only 2,210 troops returned to Britain after the mission, leaving behind 1,946

prisoners of war. [LAC/3378723]

Finally, the order was given to retreat at 11 a.m. The landing craft were to pick up only men. Tanks, mortars and anti-tank guns were all to be abandoned. Many units suffered their highest casualties as men left their protected hiding spots to escape to the approaching landing craft. Then, some vessels loaded with wounded men were struck by artillery as they attempted to launch.

Back in England, the troops began to count their casualties and returning men. Of the nearly 5,000 soldiers who had embarked on the raid, only 2,210 came back with the retreating forces; 916 Canadians died; and left behind were 1,946 men who would spend the rest of the war in prison camps.

Much finger pointing followed the disastrous raid with no one really accepting blame. Roberts was relieved of command of the 2nd Canadian Infantry

Division in early 1943 and oversaw a recruiting depot for the rest of the war. No doubt much was learned about amphibious landings during the attack, but it hardly supported Mountbatten’s claim that “The successful landing

in Normandy was won on the beaches of Dieppe.” Still Canadian veterans returning to Dieppe are treated as heroes, regularly hosted at ceremonies or paraded through town. As Canadian historian Steve Harris told veterans during

a Dieppe pilgrimage in 2002, “The important thing is what you saw as you paraded in the streets the other day. The success of Dieppe was that after three years of occupation you gave France hope.”

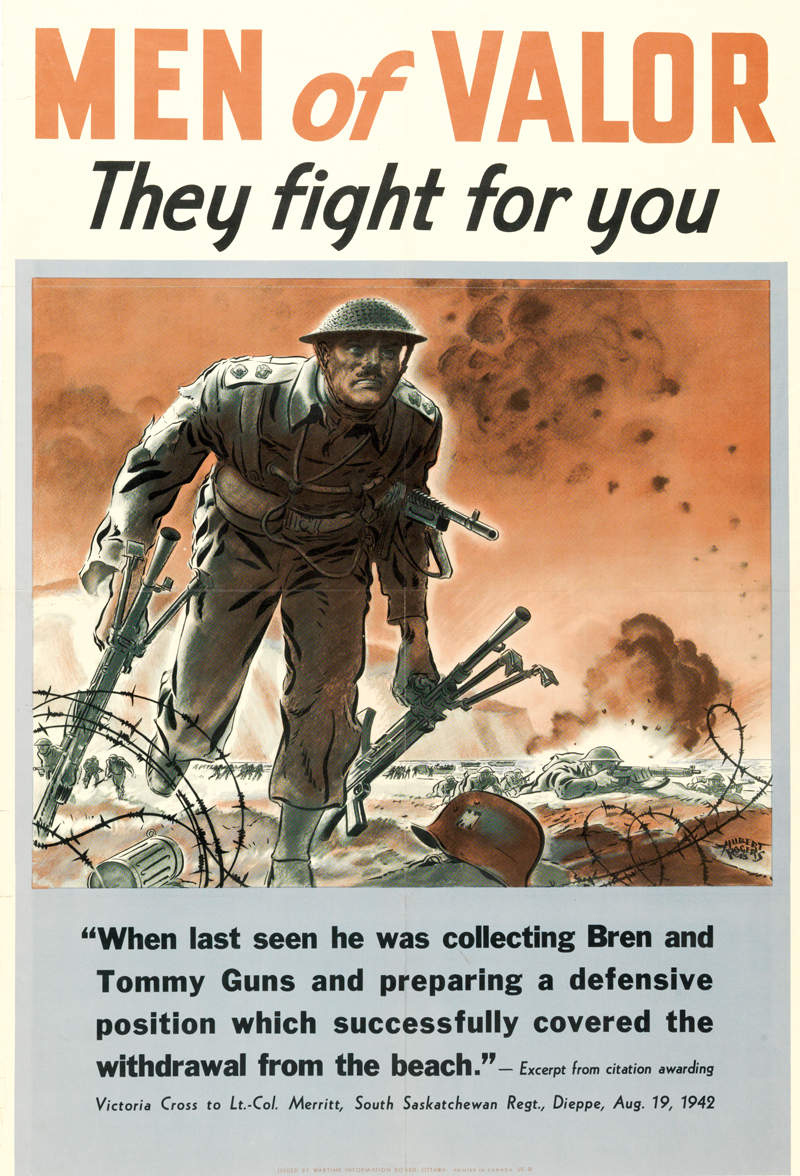

The lawyer and the stowaway

When Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Cecil Merritt saw his troops from the South Saskatchewan Regiment were pinned down by enemy fire at a bridge crossing the Scie River at Pourville west of Dieppe, he stood up, took off his helmet and waved it to the men shouting, “Come on over! There is nothing to worry about here!”

He personally led at least four parties across the bridge, even though he was wounded twice.

Throughout the battle, Merritt, a Vancouver lawyer and militia officer before the war, was fearless in his fighting. As the landing craft came in to evacuate the men, he led a rearguard action holding back the enemy while troops boarded. He fought until he ran out of ammunition, then surrendered.

A very different kind of courage was shown on White Beach during the main assault on Dieppe. When the burly Padre John Foote, who had been assigned to the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry, was told that chaplains were ordered to remain in England during the raid, he decided he had to be a stowaway.

Once he came ashore with the troops, Foote was tireless in tending to the wounded. When the evacuation began, he personally carried several wounded men to the vessels. He had a chance to board one himself, but instead insisted he was needed more by the men left behind. He returned to the beach and spent the rest of the war as a prisoner.

Merritt would be the first Canadian awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions at Dieppe. His citation appeared in the London Gazette in 1942. Foote’s heroics were only known after the war when the men he served with told his story. He was awarded the VC on Feb. 14, 1946.

[Reginald Rogers/CWM/19870123-005]

Those left behind

The Dieppe Canadian War Cemetery in northern France is markedly different from other Commonwealth graveyards. Here, in the village of Hautot-sur-Mer, five kilometres south of Dieppe, the headstones are placed back-to-back in double rows instead of single rows common in most other cemeteries administered by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC).

That is because those interred were buried by the occupying German forces following the deadly raid. When Dieppe was liberated in 1944, authorities opted not to disturb the graves.

The cemetery was designed by commission architect Philip Hepworth and was the first CWGC cemetery to be completed after the Second World War. The typical Commonwealth headstones replaced makeshift markers left by the Germans. The graveyard contains 765 war dead, including 582 Canadians. There are also 187 unidentified graves with the inscription “Known unto God.”

Advertisement