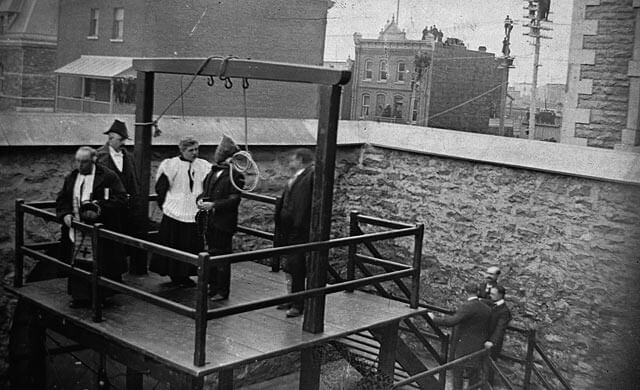

The execution of a soldier in Belgium during the First World War. [CEFRG]

An ominous warning, Lawrence had said these very words shortly after a free vote on Bill C-34 in Parliament. By a 130-124 standing, Canada had, mostly, abolished the death penalty. It still applied, under the National Defence Act, for members of the Armed Forces found guilty of cowardice, desertion, unlawful surrender, or spying for the enemy.

The decision wasn’t without controversy.

“Anyone who tells me it was a free vote lives in a dream land,” former prime minister John Diefenbaker said.

Many politicians believed they had to vote for the death penalty’s abolishment to keep their cabinet positions. Because of this, some felt that the bill didn’t truly represent the countries opinion, especially since about 75 per cent of Canadians supported capital punishment at the time.

“I feel that a free vote is in many ways an abdication of responsibility on the part of the government,” said Robert Stanbury, a then Liberal MP.

And since that fateful political move on July 14, 1976, the abolishment of the death penalty remains contentious 47 years later, with a poll issued last year showing that three in five Canadians who are 55 and over would like to resurrect the death penalty.

Before 1858, the death penalty was the judicial system’s default response to travesties big and small, situations unique or general. Killing your sister? Death penalty. Stealing turnips? Death penalty. Hiding in a forest while wearing a disguise? Odd but still the death penalty.

By 1867, almost all civilian executions were done by hanging, while military executions were by a firing squad.

The execution of Stanislaus Lacroix, March 21, 1902, Hull, Quebec.

“There is nothing more degrading to society at large than the death penalty.”

With around 250 offenses subject to the death sentence, the punishment’s liberal application was something most Canadians were used to, with a fair number even enjoying the sight of public executions.

For instance, after the public hanging of Elijah Dexter, who had murdered neighbour James Vanderburg in Toronto, on Aug. 10, 1816, the event was described as having a “great crowd” who “gave a great cheer when Dexter appeared, for many had waited hours for this show.”

“It was like going to a baseball game,” local historian Bruce Bell once told The Globe And Mail.

Upon Canada’s Confederation, however, the death penalty’s wide-ranging scope was reduced to just three offenses: murder, sexual assault and treason. But even in its shrunken form, Canadian politicians were still arched to quash capital punishment.

MP Robert Bickerdike was the first to introduce a bill that opted to replace the death penalty with a life sentence in 1916, though that bill would never make lift-off.

Christian morality as his argument, Bickerdike said, “There is nothing more degrading to society at large than the death penalty.”

Thirty-four years after Bickerdike’s bill, MP Ross Thatcher tried to do the same, this time proposing a bill to amend the Criminal Code. Thatcher’s defense, however, came from the non-secular side of ethics, citing the fact that the average time of death after hanging would sometimes be as long as 14.7 minutes.

Though his bill also went nowhere, Thatcher remained adamant, introducing a bill every year to abolish the death penalty until 1976. Funnily enough, Thatcher’s son was later saved by the 1976 abolishment after he was convicted of murdering his ex-wife in 1984.

By the ‘60s, though, the future of the death penalty started to look shaky. By 1966, Canadian politicians were finally having serious conversations about its abolishment.

These conversations followed a five-year moratorium on the death penalty and when that moratorium expired, a partial ban took its place in 1973 until total abolition, except for crimes under the National Defence Act, was set in place three years later.

Private Charles Harold. The last Canadian military member to be executed. [Hudson Louie/International Wargraves Photography Project]

“I won’t be as disappointed as the 70 per cent of Canadians who favour capital punishment,” Domm reflected upon this defeat.

“There is a sense out there that the criminal has more rights than the victim, that the punishment doesn’t fit the crime. There is a growing feeling of fear,” Progressive Conservative MP Albert Cooper stated.

Still, the abolishment remained steadfast, and finally on Sept. 1, 1999, Bill C-25 ended the threat of the death penalty for military crimes.

The last Canadian, and only one during the Second World War, to be executed on military charges was Private Harold Pringle. He left his regiment in central Italy to join a gang of deserters smuggling goods into Rome. The gang, known for being rowdy and getting drunk, got into a dispute one night and a member was shot dead. Pringle was found guilty of the murder, along with desertion. He was killed by firing squad in Italy on July 5, 1945.

During the First World War, 25 executions took place on charges of cowardice and desertion. On Aug. 16, 2006, 23 of those soldiers were pardoned.

Advertisement