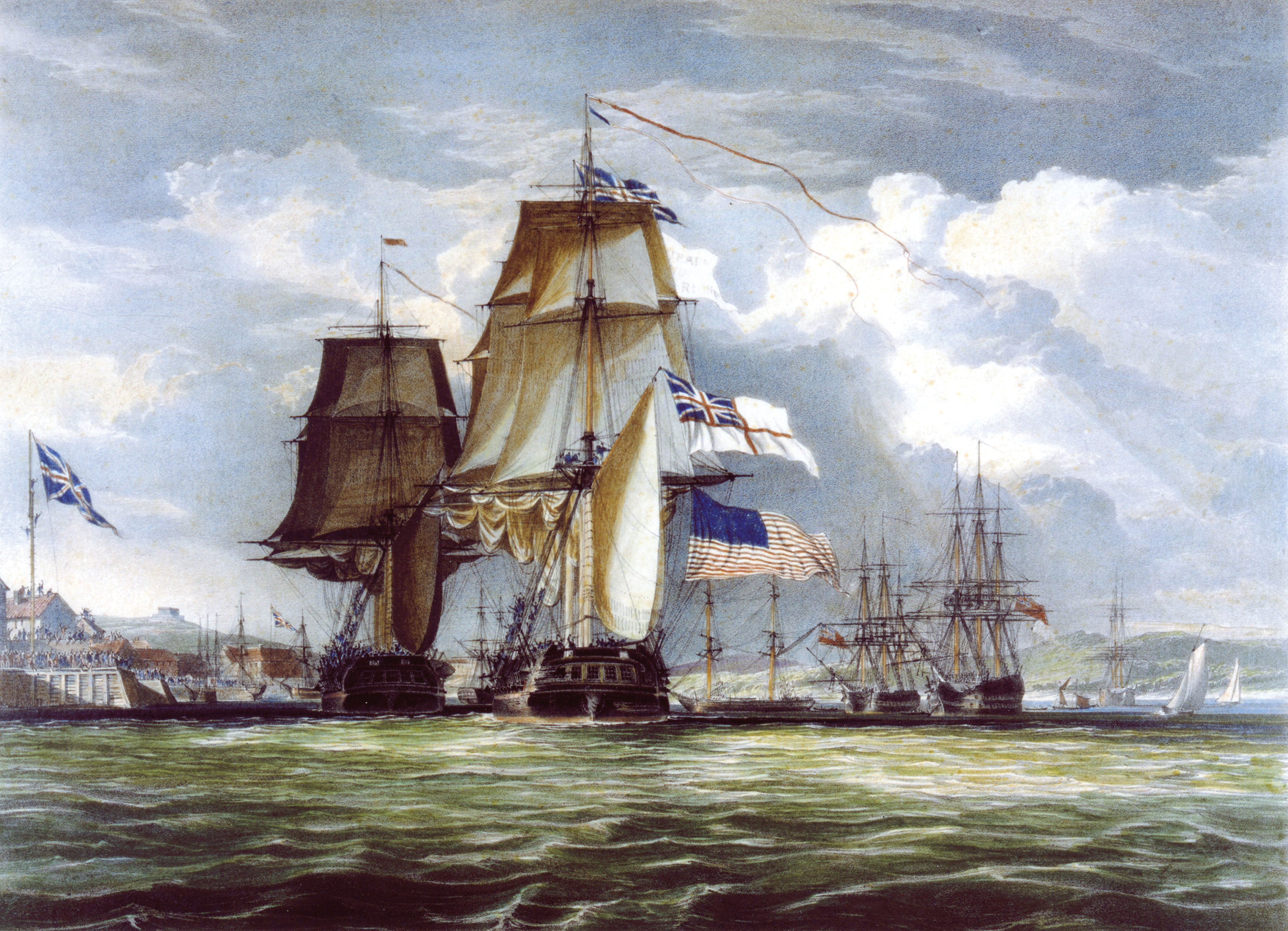

To great fanfare, HMS Shannon escorts USS Chesapeake into Halifax Harbour on June 6, 1813, five days after defeating her in a bloody 10-minute battle off Boston. It was Britain’s first sea victory of the War of 1812. [ILLUSTRATION BY: JOHN CHRISTIAN SCHETKEY, LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA—C041824]

Less than a century after the Americans were defeated in the War of 1812, the U.S. Naval War College, Class of 1894, came up with a hypothetical plan to give it another try—by invading Halifax and destroying Pictou County’s coal mines.

In the paper Attack on Halifax and Adjacent Territory, Lieutenant John J. Hunker USN and his classmates produced a sharply handwritten plan for an imagined war with Great Britain, from pre-invasion spying to assembling a convoy at the Penobscot River and landing it 310 nautical miles later in St. Margarets Bay, west of Halifax.

The 16-page document suggests an expeditionary force of 10,059 officers and men would suffice “to harass the enemy’s garrison and arsenal at Halifax, to interrupt the lines of communication with that point and the scenes of operation against our coast…to destroy railways in adjacent districts, to destroy the means of operating the coal mines in the county of Pictou.”

The paper, detailed down to the prevailing north-to-northwest winds of late fall and the paramount need for “good foot-gear” to counter likely snow and frost, was considered so sensitive it was only recently declassified by the U.S. Department of Defense under 1972 legislation aimed primarily at Second World War records.

The force envisioned by Hunker and his classmates—most would have been seasoned naval officers upgrading their education and qualifications—would include infantry, artillery, cavalry, engineers and “as few horses as possible.”

Attack on Halifax and Adjacent Territory, a hypothetical plan drawn up in 1894 by Lieutenant John J. Hunker USN and classmates at the U.S. Naval Warfare College in Newport, R.I. [U.S. Naval Academy/U.S. Department of Defense]

The troops, it said, should come from New England because it would be more efficient to get them to the objective from there and soldiers from the area would be “more or less familiar” with the lay of the land.

“The exercise was intended to sharpen the strategic thinking of the naval officers attending the college,” said the U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command, which published the paper without fanfare in August. “The purpose of the proposed expedition was to inhibit the enemy’s ability to attack the East Coast of the United States by depriving the enemy of a nearby naval base and a source of fuel for its coal-powered warships.”

The previous such enterprise did not fare so well. Between 1866 and 1871, primarily American members of a secret society of Irish patriots called the Fenian Brotherhood, many of them U.S. Civil War veterans who had emigrated from Ireland, thought they would take Canada by force and exchange it with Britain for Irish independence.

Over five years, they launched a series of small, ill-conceived incursions into Ontario, Quebec and Manitoba, all of which were repelled by army and militia—and condemned by American leadership.

There were dozens of casualties on both sides and the movement fizzled, but not before it had exposed weaknesses in Canada’s leadership and defences, and inspired broadened support for Confederation in 1867.

Modern-day Halifax with Citadel Hill. The masts on which the semaphore flags were raised can be seen in the southeast corner of the fort, nearest the harbour. [Nova Scotia Tourism]

In Britain’s first major sea victory of the war, HMS Shannon captured the USS Chesapeake and paraded her prize up Halifax Harbour. In 1814, an invasion force departed Halifax for Washington, D.C., where it famously burned the Capitol and the White House, which wasn’t painted white until after the invaders had blackened it.

A half-century later, the American Civil War proved a boon to Halifax, which supplied the wartime economy of the North while at the same time offering refuge and supplies to Confederate blockade runners.

By the time the college paper was written in 1894, the Age of Sail was over and the city’s population was all of about 4,000. But Halifax had shored up its defences—the Citadel had been designed especially to repel a land-based attack by U.S. forces—and the port now boasted the largest dry dock on the eastern seaboard.

The U.S. Navy pays regular—friendly—visits to Halifax. Here, the USS Valley Forge arrives at Halifax with crewmen in formation spelling out HELLO HALIFAX on her flight deck on July 10, 1959. She was accompanied by a task force that included seven destroyers and two submarines. Altogether, about 4,000 American sailors were in the city for a six-day visit. [U.S. Navy Photograph, from the collections of the Naval History and Heritage Command/NH 96939]

Hunker wrote that the destination of the hypothetical invasion force should be kept “a profound secret” and that once the decision was made to proceed, planners should resort to “all possible means of ascertaining the condition of the objective.”

“To obtain this information a body of astute, intelligent men should be selected to comprise a secret service, and placed in [the] charge of an officer familiar with such work,” he wrote. “Such a man could be readily selected from the detection forces of our large cities.”

Overland telegraph lines would be seized by the military authorities, along with the three submarine cables linking Massachusetts (two) and New Hampshire with Nova Scotia.

The year the plan was written, 1894, just happened to be when Guglielmo Marconi began developing a wireless telegraph system using radio waves (he didn’t send his first transatlantic message from Signal Hill in St. John’s, N.L., until 1901).

Semaphore, the system of signal flags, was still in use for ship-to-ship and ship-to-shore communication. Today, re-enactors demonstrate signals during tourist season as they were conducted in the 19th century between the fort on Citadel Hill and the relay station nine miles out at Chebucto Head, beyond the harbour mouth.

The paper suggested the American force should set sail for Halifax, then reroute to St. Margarets Bay—now prime cottage country—once the opposing navy, assuming it had been alerted, had sailed beyond signals range.

“Ingress and egress [at St. Margarets] is easy, the entrance being two miles wide, sufficient sea room in case of fog or storms, is well sheltered, good anchorage and it contains a number of islands useful for a variety of purposes, such as hospitals.”

The beaches where children play and sunbathers bask today were considered by the naval plotters to be “practicable” and easily reinforced landing areas.

Once at anchor, the transport fleet “should be carefully guarded by the convoy, and the torpedo boats be in readiness to attack.”

What was then barely a sleepy fishing village, if that, was just 20 miles from Halifax, the students noted optimistically (the shortest way is actually 28; the scenic route, 33), and it afforded the invaders access via the peninsular city’s least-defended landward side by dawn’s early light. This was, of course, before morning traffic presented its own form of defence, choking modern-day access to the port and fortifications downtown.

The paper said raiding parties should depart in force for Pictou, 70 miles from Halifax by their estimates, soon after landing. There, they were to overcome any resistance and blow up coal mines with “heavy charges to destroy the shafts, and tunnels, and render the mines incapable of being worked.”

“The tressels [sic] and all inflammable material should be put to the torch; the hoisting and transporting machinery be destroyed or injured beyond repair,” it said.

“This accomplished the retreat should be along the line of railways to the main body, destroying the [railway] as soon as passed over, by burning or wrecking bridges, culverts, heating and bending the rails, and other devices, so frequently practiced during the late civil war.”

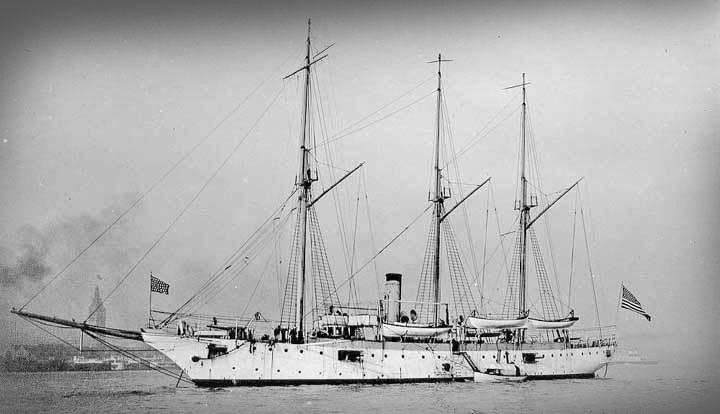

The gunboat USS Annapolis pictured during later years when she was employed as a training vessel at the Pennsylvania Maritime Academy. During the Spanish-American War, the ship was commanded by John J. Hunker. [U.S. Naval Archives]

The commander-in-chief, President Grover Cleveland, was to be given regular updates of the mission’s progress. The whole thing was not to take more than 10 days.

The esteemed Naval War College, located at Newport, R.I., was just 10 years old at the time the hypothetical scheme was hatched. Today, Canadian and British naval officers alike attend its classes alongside their American counterparts.

Pictou County is down to its last coal mine, an open-pit operation in Stellarton whose product helps fuel the provincial power grid, not ships. American invaders of another sort have bought up a disconcerting chunk of prime oceanfront real estate along Nova Scotia’s scenic South Shore. Nevertheless, Halifax remains a thriving port and naval base, and receives regular—friendly—visits from its U.S. Navy brethren.

A graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis, Md., Hunker commanded the USS Annapolis with distinction during the Spanish-American War just a few years after authoring the paper. He was promoted to rear-admiral in 1906 and retired two years later. Hunker died in Asheville, N.C., in 1916, age 72.

Advertisement