Legion Magazine sat down with Lt. (N) Jason Delaney, Naval Historian at the Directorate of History and Heritage for the Department of National Defence, to discuss Canada’s hydrofoil project of the 1960s – HMCS Bras d’Or. During sea trials in 1969, the vessel exceeded 63 knots (117 km/h; 72 mph), making her the fastest unarmed warship in the world at the time. The project was ultimately scrapped, but lots can be learned from it. This is part 1 of 2 videos on Canada’s Hydrofoil.

Browse our previous artifacts video interviews here.

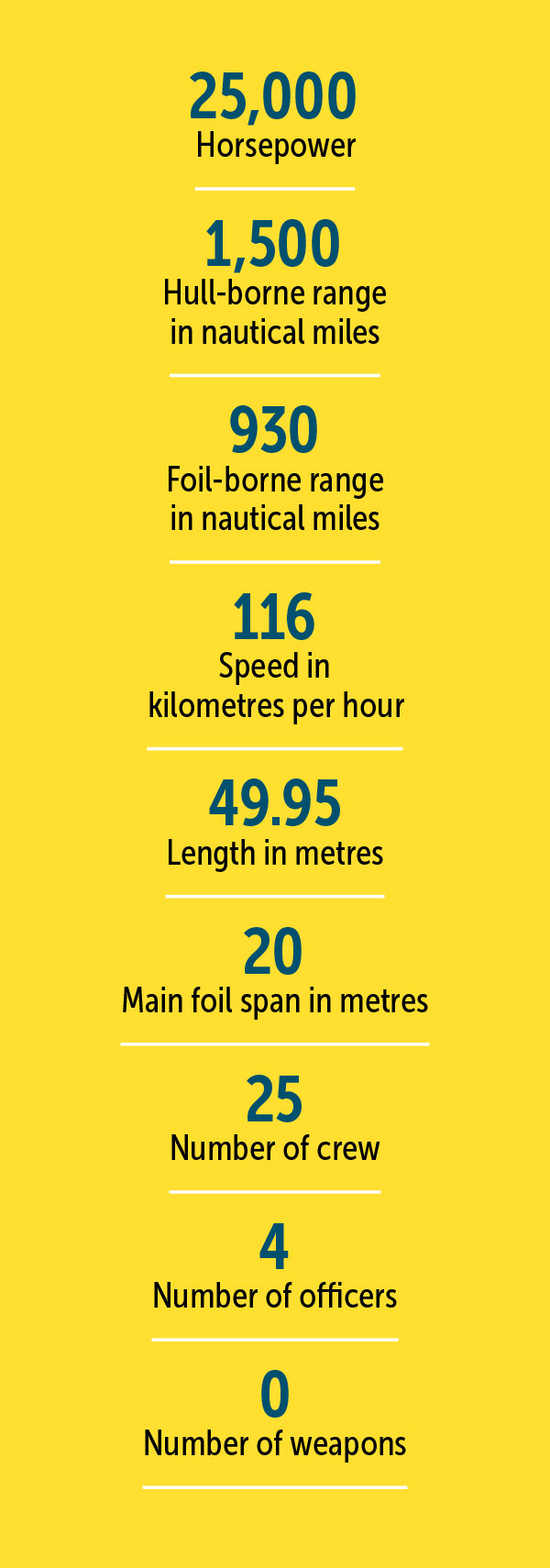

Hydrofoils protruding from the hull allowed HMCS Bras d’Or (FHE 400) to soar above the water in tests in the 1970s, reaching speeds of 63 knots (116 kilometres per hour), double the top speed of Canada’s destroyers and frigates today. [LAC/R112-5519-2-E]

During the Cold War, fast and deadly Soviet nuclear-powered submarines were deployed along the North American coast, capable of launching a nuclear weapon attack practically without warning.

Tasked with anti-submarine duties by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Canada upgraded its fleet and modernized equipment.

But it was also keen to develop a ship that would be capable of detecting one of these subs, and then quickly accelerating to intercept it, regardless of rough seas.

Battleships are not known for great acceleration and speed, as most of their power is used to overcome friction on their hulls as they plow through the water. But what if the hull could be lifted clear of the waves?

Canada’s Defence Research Board, formed in 1947 for postwar military research, tackled the problem by delving into technology perfected in Canada in the First World War.

In 1919, when the fastest steamship’s top speed was only 48 kilometres per hour, Alexander Graham Bell and Frederick (Casey) Baldwin designed a ship that set a world marine speed record—114 kilometres per hour.

Bell and Baldwin designed airfoils and hydrofoils, technology that allows aircraft to sail through the sky and watercraft to fly over the sea.

Alexander Graham Bell (inset), Frederick (Casey) Baldwin and Baldwin’s son Robert aboard an experimental hydrofoil on Bras d’Or Lake, N.S., in 1919. [Granger Academic/0622504]

A foil, such as an airplane wing, has a flat bottom and curved upper surface. At speed, air is directed downward, increasing pressure beneath the foil, while the foil’s curve increases the speed of the airflow over the top, reducing pressure above. This creates the lift needed to raise a plane from the runway. The same principle is used to raise a ship’s hull from the sea. A hydrofoil thus allows a ship’s power to be devoted to speed, rather than fighting friction along the hull.

Several designs were tested in the 1950s. In 1963, the Royal Canadian Navy contracted de Havilland Aircraft Company of Canada to build a hydrofoil. In July 1968, after a delay of nearly two years due to a fire, the hydrofoil vessel was commissioned into the navy as HMCS Bras d’Or, named for the lake where Bell and Baldwin tested their models.

During trials, the ship travelled at 116 kilometres per hour, but it was plagued by problem after problem. Despite this, Lieutenant-Colonel Gordon Edwards, the ship’s captain in 1970-71, grew to love Bras d’Or.

“We showed her off whenever we could,” said Edwards in the foreword to Thomas Lynch’s The Flying 400: Canada’s Hydrofoil Project. During one demonstration, he said, “after doing a slalom down the formation of ships, then a turn around them all, I gilded the lily by going past the flagship literally ‘waggling’ my wings.”

Originally called the Bras d’Or, a one-third size experimental hydrofoil commissioned by the Royal Canadian Navy was renamed HMCS Baddeck to free up the name for the full-size hydrofoil vessel. [Alamy/F62YN4]

As development costs of Bras d’Or climbed to $50 million (equivalent to $310 million today) and glitches and problems continued, helicopter/destroyer teams were proving that they were capable of anti-submarine operations. As well, Canada’s defence policy focus moved from submarines to sovereignty. The hydrofoil project was cancelled in 1971.

HMCS Bras d’Or is now on display at the Musée maritime du Québec at L’Islet-sur-Mer, an hour’s drive east of Quebec City on the southern shore of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence.

Advertisement