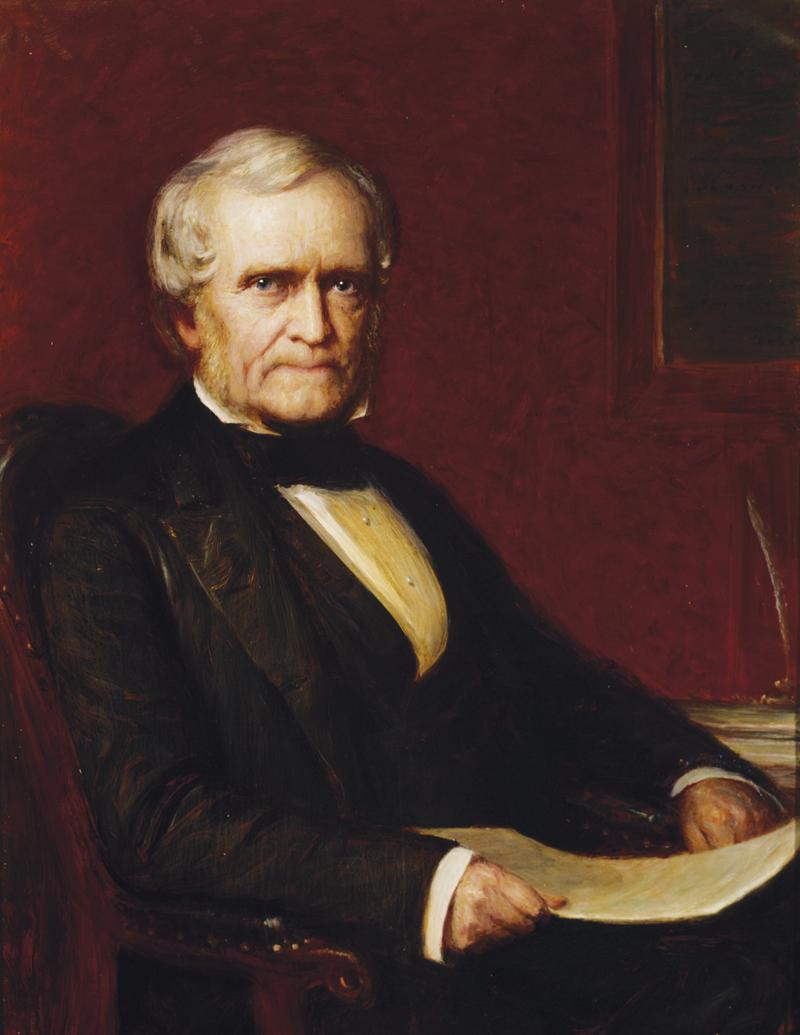

William Lyon Mackenzie was a short, combustible, red-haired Scottish immigrant who coined the term “Family Compact.” He used it to describe the small network of wealthy elite who governed Upper Canada in the first half of the 19th century.

“I had long seen the country in the hands of a few shrewd, crafty, covetous men,” he wrote in his newspaper the Colonial Advocate.

His opinion made him hugely popular with other reform-minded colonists. It also made him deeply despised by the local oligarchy. The former elected him to the legislature. The latter attacked him in the courts, on the street, and finally, in the offices of the Advocate, where they smashed his printing press and threw the type into Lake Ontario.

His popularity continued to grow, however, and in 1834, Mackenzie became Toronto’s first mayor, while keeping his job as Advocate publisher and his seat as a member of the Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada. Mackenzie also kept hounding the establishment, writing a 500-page list of demands titled The Seventh Report on Grievances that he sent to London. His chief complaint? Upper Canada wasn’t really a democracy, but rather the lieutenant governor held the real power.

Mackenzie lost his seat in the legislature in 1836, and a year later he was plotting rebellion. In November 1837, virtually all the British troops stationed in Toronto left to deal with rebels in Lower Canada, where Louis-Joseph Papineau was voicing similar complaints. Under Papineau, the Patriotes had advocated for responsible, representative government—and they were prepared to fight for it.

“I had long seen the country in the hands of a few shrewd, crafty, covetous men.”

Mackenzie felt they had to seize the moment. He recruited disgruntled farmers and told them to meet at Montgomery’s Tavern just north of Toronto. His plan was to overthrow the legislature and form a provisional government.

On Dec. 5, Mackenzie led several hundred farmers down Yonge Street. While the soldiers had left town, some members of the militia were still in the city. A small group of them fired on the crowd.

The farmers fled. “The city would have been ours in an hour,” Mackenzie wrote, “probably without firing a shot.” But 800 ran.

On Dec. 7, a thousand volunteer militia were given weapons and they marched toward Montgomery’s Tavern with orders to rout the rebels. There were only 400 objectors left—the rest having already returned to their farms—and only half of them had guns. The militia fired cannonballs through the tavern, and the rebels retreated. The battle lasted just minutes. The militia torched the bar. Mackenzie fled to Buffalo, N.Y.

Several of the rebels were executed, hundreds of others were imprisoned and charged with treason, and dozens were shipped to Australia, then a penal colony. They argued that they weren’t trying to overthrow the crown, but a corrupt colonial government, a distinction that was lost on the authorities.

Mackenzie was pardoned in 1849 and returned to Canada. He was once more elected to office and continued to denounce the corrupt, cozy Family Compact. He died in 1861, but his impassioned advocacy for democracy and for openness in government affairs remains a model today. Simply, Mackenzie spoke truth to power.

Advertisement