German Admiral Karl Dönitz with the crew of U-94 at Saint-Nazaire, France, in June 1941. [Wikimedia]

The sinking of U-94 by an American aircraft and HMCS Oakville off Cuba on the night of Aug. 27-28, 1942, brought to a dramatic end the submarine’s relatively long and eventful service in the Kriegsmarine.

Commissioned in August 1940, U-94 had sunk 26 Allied ships in two years, totalling 141,852 gross register tons, under the successive command of two Knight’s Cross recipients, Kapitänleutnant Herbert Kuppisch and Oberleutnant zur See Otto Ites.

But a year before the tide of battle shifted in the U-boat war, the interrogations of U-94’s 26 survivors told other stories—of joyful encounters with porpoises the crew at first mistook for torpedoes; gifts of music and money from German corporations; and near-fatal sabotage engineered by Polish slaves during a refit.

The 29-ship convoy TAW-15, transporting Caribbean oil north, had already lost two tankers sunk and another damaged by U-511 on Aug. 27 by the time U-94 was sighted and attacked by an American PBY.

A convoy at sea. [Wikimedia]

Powell and Lawrence shot two Germans before the latter headed below, alone.

The damaged Type VII C U-boat was forced to the surface where Oakville, one of three corvettes escorting the merchant vessels from Trinidad to Key West, Fla., rammed it three times and peppered the German boat with shells.

Sub-Lieutenant Hal Lawrence and Petty Officer Art Powell led a small boarding party onto the deck of the crippled U-94 and rushed toward the heavily damaged conning tower.

Powell and Lawrence shot two Germans before the latter headed below, alone. Their boat sinking, the German crew surrendered. Probing the darkness, Lawrence went looking for the vessel’s Enigma code machine and documents. They’d been scuttled, along with the boat, and the Canadian waded through waist-deep water on his way out. Shortly after, all aboard leapt into the ocean and U-94 slipped beneath the waves.

Sub-Lieutenant Hal Lawrence (left) and Petty Officer Art Powell would become national heroes in Canada. [DND/LAC/PA-106526]

Interrogators arrived from Washington on Aug. 29 and took most of the U-boat crew to the United States two days later. The wounded men would follow.

Ites was a prize catch, though the U.S. Navy’s report said he was “amiable and courteous but adamantly security-minded.” The other survivors—a senior midshipman, nine petty officers and 15 enlisted—were well trained and experienced, it added, but several “appeared not to have received recent instruction in security, and responded readily to early interrogations.”

Oberleutnant zur See Otto Ites, commander of U-94.

At just 24, Ites was the youngest of the so-called “star” commanders in Admiral Karl Dönitz’s vaunted U-boat fleet. Skippering U-146 and U-94, Ites had sunk 15 merchant ships for a total of 76,882 tons by the time he was captured. U-boat captains recorded their sinkings by ship’s name and “gross register tonnage,” a nautical term reflecting the measure of a ship’s carrying capacity, by volume.

He had served in subs since the war began but told his interrogators that the 1,000+ depth charges he’d heard explode around him had not affected his nerve. He was on his fifth war patrol in command of U-94.

“His control of his boat and his men were belied by his ingenuous appearance,” said the interrogation report, submitted to the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations in Washington on Oct. 25, 1942.

“His success as a U-boat commander could be attributed to several factors, not the least of which was the ability to keep his crew relatively intact over an extensive period.”

He accomplished this, said the document, despite the fact his returning crews were routinely sifted by the German Navy’s U-boat Arm headquarters, looking for officer and non-commissioned officer candidates and experienced hands for new U-boats.

“Prisoners said that Ites always had at least one experienced man on each watch,” wrote the interrogators. “Ites’ apparent favor with the B.d.U. [U-boat headquarters] enabled him to have two of his petty officers commissioned, and to regain them after their schooling.

“Daring and nerveless, he was admired by his crew as a fighter. Friendly and talkative, he made himself one of his men, who referred to him as ‘Unser (Our) Otto’ and ‘Onkel Otto.’”

U-94’s second watch officer, Oberfähnrich (senior midshipman) Kurt-Rolf Gebeschus, was the son of a U-boat officer killed in the First World War. His mother later married his father’s brother, who had been taken prisoner by the British in the First World War and was, at that point, a captain stationed at Naval High Command in Berlin.

The highly educated and well-travelled Gebeschus, 24, had been a Scharführer (troop leader) in the Hitler Youth Movement. As second watch officer, he was U-94’s torpedo and artillery officer.

“The crew as a whole was one of the most experienced thus far captured in American waters,” said the report. “Although only one of the crew, a machinist’s mate, had been on all the cruises of U-94, all the older members…were seasoned U-boat men.”

This would change as U-boat losses mounted the following year—from 87 sunk in 1942 to 244 in 1943 and 249 in 1944—and new, untested crews were pressed into U-boat service.

Ites’ predecessor Kuppisch had served five cruises aboard U-94, sinking ships on all but his last patrol before nerves forced him ashore for a time in 1941.

“Kuppisch’s nervous condition apparently had grown worse on his last cruises,” said the report. “One prisoner stated Kuppisch was exceedingly nervous when departing on, and returning from, a cruise, but that once at sea his anxiety lessened. Prisoners said he held himself apart from the crew.

“Ites succeeded to his command of U-94 on August 18, 1941. One prisoner who saw Kuppisch a year later said he looked ‘fresh’ and apparently recovered: nevertheless other prisoners expressed the opinion that he never would go to sea again.”

Kuppisch did return to sea, and died aboard U-847 after it was attacked by aircraft from the escort carrier USS Card on Aug. 27, 1943.

U-94’s crew varied in their recollections of Ites’ first cruise aboard their sub. One said the boat sank four merchant ships for 29,900 tons; others claimed they sank five or six, totalling 32,000 tons.

After nearly five weeks at sea, U-94 headed for home, making port in Bergen for several days before eventually ending up in Stettin, in what was historically part of Poland, for refit the third week of October. (Stettin had been part of the German Empire since the 18th century, but was returned to Poland and renamed Szczecin at war’s end).

Crew received up to a month’s leave in staggered groups while U-94 was thoroughly overhauled at the Oderwerke, a German shipbuilding company employing Polish slave labourers. The workers’ commitment to their jobs was commendable—from an Allied perspective.

“There is good reason to believe that the repair work on U-94 at the Oderwerke in Stettin suffered grossly from inefficiency, negligence or sabotage,” said the report. “The U-boat was in such precarious shape upon leaving Stettin that, according to prisoners, she almost sank on the trial run to Kiel.”

“Precarious” and the terms “inefficiency” and “negligence” seem understatements. Among the problems U-94 encountered on its trial run after the refit:

- a part was removed from a valve, which allowed water to pour into the boat as it attempted to submerge;

- some wiring in the boat’s diesel engines was cross-connected;

- the batteries and apparatus connected with the batteries were damaged;

- the indicators for ‘Ahead’ and ‘Astern’ were inverted;

- and the main bilge pump was unusable.

“Apparently there was considerable trouble stirred up by authorities after U-94 reached Kiel” in January 1942, wrote the interrogators. There, the boat’s ills were evidently remedied before it set out on its seventh of 10 war patrols, a month-long venture to the Shetland Islands.

Ites’ third cruise commanding U-94 took them to the American coast for the first time, where they spent a week plying the waters between New York and Chesapeake Bay. Crew testified they sank several ships, and two more in a convoy on the way home, for a total of between five and eight, or nearly 40,000 tons.

At one point a blimp sighted the U-boat and dropped bombs periodically for several hours, causing no damage, but unnerving the crew since their maneuverability was limited by shallow waters.

They returned to sea on their second-last cruise in May, operating in mid-Atlantic south of Iceland after a layover in Saint-Nazaire, France. One of the crew told his interrogators that each Monday a convoy passed them in the same position.

Most prisoners agreed that they sank six ships from two convoys, along with a Canadian sailing vessel, totaling 30,000-35,000 tons. They claimed to have attacked the convoys on the surface and escaped the fight without submerging, before returning to Saint-Nazaire in late June after seven weeks at sea.

Gebeschus claimed that groups of porpoises frequently accompanied the U-boats for hours on end.

U-94’s deployment to the Caribbean was intended to be a reward for a job well done. Crew said they had been “promised” a trip to southern waters after operating for so long in the cold North Atlantic.

They sailed past the Azores at slow speed, the crew taking turns sunbathing on deck en route. Even the technical men who, according to the crew, were not allowed beyond the conning tower when at risk of an air attack, were permitted to relax on the upper deck before they sighted land again on Aug. 20.

Gebeschus claimed that groups of porpoises frequently accompanied the U-boats for hours on end.

“He related that once when he was serving as lookout he saw, at about 120 feet, what appeared to be the white track of a torpedo headed for the U-boat,” said the report. “He gave the alarm, then discovered that it was a porpoise.

“He said Ites scolded him for his mistake, but at that very moment Ites, himself, saw a white track speeding toward the U-boat. When that turned out to be a porpoise, Ites breathed a sigh of relief and retracted his scolding.”

The skipper was nevertheless a keen submariner. He was said to have suspected a convoy was approaching on Aug. 27 when he sighted PBYs, which he presumed to be serving as convoy scouts. He spent a good part of the day successfully dodging the planes, but his success would ultimately prove his undoing, as he became reckless after nightfall.

PBY Catalinas from the U.S. Navy’s Patrol Bombing Squadron fly over the Caribbean Sea in 1942. [U.S. Navy/uboatarchive.net]

In moderately heavy seas, U-94 lay on the surface beneath a full moon. Ites had maneuvered inside the convoy screen and was readying a torpedo for an escort destroyer when a lookout sighted a plane. The boat’s executive officer, who was looking at another sector, is said to have replied: “You are seeing ghosts.”

“However, the ‘ghost’ was a U.S.N. PBY plane, and U-94 crash dived,” said the report. “Ites cursed and remarked to Gebeschus: ‘I’ve avoided that plane all day, and now that I’m ready to attack he sees me.’”

The plane dropped multiple 650-pound depth charges from 50 feet and a flare to mark the spot. U-94 was between 30 and 60 feet below the surface, according to the crew’s estimates.

The U-boat nosed upward and surfaced. The crew tried in vain to take it down again. According to the intel report, Oakville closed at full-speed ahead toward the flare, dropping five depth charges set at 100 feet on the way.

Oakville then got a ASDIC (sonar) contact. Within 30 seconds, a lookout sighted the submarine’s bow less than 100 metres almost dead ahead.

Oakville’s Lieutenant-Commander Clarence King altered course to ram. The U-boat passed under the corvette’s bow, bumping against its port side when the Canadian turned hard to port. Oakville opened fire and altered course to ram again.

The scrubby little ship scored a hit on U-94’s conning tower; a four-inch shell blew off the U-boat’s deck gun. The sub increased speed. Oakville rammed it again, this time on the starboard side, then dropped depth charges, one of which exploded directly under the U-boat.

The U-boat slowed and Oakville opened range, then turned and rammed a third time, this time squarely abaft the conning tower.

Ites ordered the vents opened and declared: “Alle Mann aus dem Boot (abandon ship).” Shortly after, the skipper was shot in the leg. Gebeschus went to the bridge and laid flat as machine-gun bullets zipped overhead and clanged into the superstructure.

A seaman, Hermann Schee, was struck by a wave as he left the conning tower and was thrown headfirst back down when his leg caught in the hatch.

“He hung there suspended, unconscious,” said the report. “A shipmate named Mecklenburg pulled him loose and carried him on to the deck, where Schee recovered consciousness.

“He subsequently was rescued but Mecklenburg drowned.”

Oakville was laid alongside, and the boarding party leapt aboard. When two men appeared in the conning tower hatch and ignored Lawrence’s order to stop, he shot one—Leutnant Heinrich Müller. The second was shot when he lunged toward Powell, the petty officer. Prisoners claimed Müller was attempting to surrender.

Lawrence allowed the remaining Germans to come out and placed them aft under Powell’s watchful eye. He then descended the conning tower and found all the lights below were out. The lower deck was flooded more than a metre. The air smelled of gas. The submarine lurched. Unable to find any intelligence, Lawrence grabbed four pairs of binoculars and exited the boat.

He then ordered everyone overboard. They were about 15 metres away when the U-boat’s bow rose high in the air and U-94 plunged to the bottom.

USS Lea collected 21 survivors; Oakville picked up the rest.

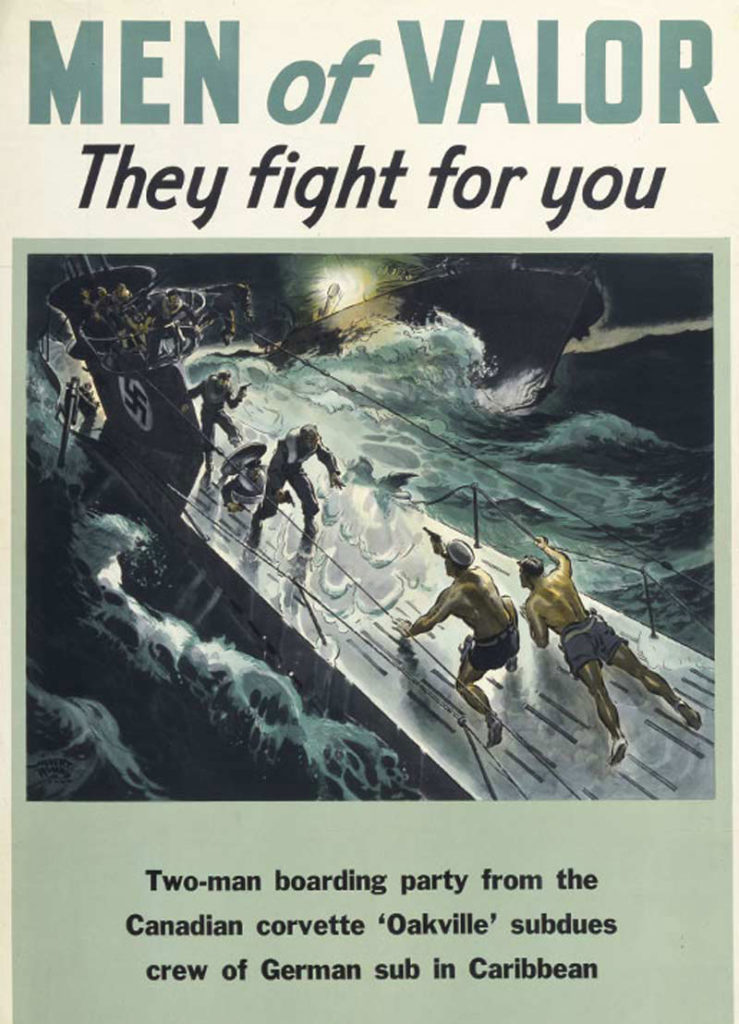

A propaganda poster depicting Hal Lawrence and Art Powell during the perilous boarding of U-94 in August 1942. [Reginald Rogers/CWM/19750317-102]

The prisoners’ testimony shed light on U-boat technologies and operations, the status of various U-boat commanders, the effects of a commando raid on Saint-Nazaire and the rewards and pitfalls of U-boat service.

U-94 had a sponsor firm—known as a patenfirma—the shipping concern Schenker and Company (an Austria-based corporation which today has a Canadian office). It sent oranges and chocolate to families of the crew, as well as cigarettes, gramophone records and money to the sailors.

One crew member said he received 40 marks from the patenfirma, which he “drank up.” He told interrogators that the amount of the gift depended on length of service. Schenker adopted U-94 in the summer of 1942 after Ites gave a talk at an event the company’s employees put on for the crew.

The unterseeboots suffered the highest casualty rates of all the German military services of the Second World War.

Ites told his interrogators that crews “suffered no strain crossing the Atlantic to and from operations areas in American waters, as these periods were regarded as pleasure cruises.”

“The real strain began when the boat reached its operations area,” said the report. “He indicated that 4 weeks at a stretch on such patrol was about as much as the nerves of a crew could stand.”

The unterseeboots suffered the highest casualty rates of all the German military services of the Second World War: as many as 784 boats and some 28,000 of 40,900 crew were lost; another 5,000 were taken prisoner. Some 30,000 Allied merchant mariners died between 1939 and 1945.

Ites’ twin brother, Oberleutnant zur See Rudolf Ites, was killed in action when the U-boat he commanded, U-709, was sunk by American destroyers on March 1, 1944. Ites earned a medical degree after the war and later joined the West German navy. He commanded a destroyer, then became an admiral before he retired in 1962. Ites died in his hometown of Norden, Germany, in 1982, aged 63.

—

Read Marc Milner’s article on the actions of HMCS Oakville and its crew during the sinking of U-94 on the Legion Magazine website.

Advertisement