HMS Victory at the Battle of Trafalgar, Oct. 21, 1805. Nelson’s flagship is estimated to have required 6,000 trees, 90 per cent of them oak. [JMW Turner/Wikimedia]

At the zenith of Horatio Nelson’s navy in the late-1700s into the 1800s, it took about 4,000 oak trees, or up to 40 hectares of forest, to build a single 100-gun ship of the line. That’s equivalent to 3,750 city blocks of optimum-density oak forest for a vessel that, on average, sailed for 12 years.

In 1790, shortly before the legendary admiral embarked upon more than a decade of successive victories at sea that cost him vision in his right eye, his right arm and, in 1805 at Trafalgar, his life, the Royal Navy’s entire sailing fleet consisted of some 300 ships.

It’s estimated it took 6,000 trees to build the ship.

Historians and tree experts estimate that number of vessels would have required at least 1.2 million of the best oak trees Britain and Europe could harvest.

Shipbuilders laid the keel of Nelson’s own HMS Victory, arguably the most famous warship ever to sail the seas, in July 1759 at the RN’s Chatham Dockyard on the River Medway in Kent. It took a year to come up with a name that, some say, commemorated Britain’s victory over the French in Quebec that September.

It’s estimated it took 6,000 trees to build the ship. Ninety per cent of it was oak, some of the timbers more than half-a-metre thick.

HMS Royal George at Chatham Dockyard on the River Medway in 1790 with HMS Queen Charlotte under construction. [Nicholas Pocock/Wikimedia Commons]

Some of those trees were over 400 years old, their lifetimes spanning the reign of kings great and small, Francis Drake’s circumnavigation of the globe and the burning of the Spanish Armada. There were plagues, revolts and executions aplenty. London was ravaged by the Great Fire, Shakespeare authored some of history’s greatest plays, and English troops fought Scottish clans at the Battle of Culloden.

But, for the trees, it was the onset of exploration, discovery, trade and conquest that changed everything. It all demanded ships, and ships demanded timber.

Huge elm trunks formed Victory’s keel; fir and spruce were used for decking, yardarms and masts, each mast requiring seven trees. With the Seven Years’ War coming to an end, the ship’s assembled frame was covered and left to season for three years—a major reason, it is said, that the vessel remains so well-preserved at the National Museum of the Royal Navy in Portsmouth.

He dubbed it “the timber problem.”

Work resumed in 1763 and Victory, a triple-decker equipped with 100 guns and manned by up to 875 sailors, was launched in May 1765 at a total cost of about £63,000, or approximately C$80 million today.

The ship saw much action and numerous repairs and refits—consuming even more trees—before it was, for all intents and purposes, retired from seagoing service at the end of the Napoleonic Wars.

Old English oak was the preferred timber for sailing ships, particularly warships, primarily because of its strength and durability. In its day, the oak was abundant, but 18th and 19th century harvesting took a lasting toll. [lovethegarden.com]

American historian Robert G. Albion’s doctoral dissertation, Forests and Sea Power: The Timber Problem of the Royal Navy, 1652–1862, was published in 1926. In it, he hypothesized that the RN’s huge demand for timber to build and repair wooden ships stripped the landscape of trees. He dubbed it “the timber problem.”

Albion went on to become the first professor of oceanic history at his alma mater, Harvard, and his work inspired two generations of maritime historians. Based on his findings, many considered 18th and 19th century English shipbuilding a major cause of deforestation in the British Isles.

British historians subsequently re-evaluated the subject and shifted the consensus. In his 1990 book Trees and Woodland in the British Landscape: The Complete History of Britain’s Trees, Woods and Hedgerows, Oliver Rackham wrote that “the ‘tradition’ that [shipbuilding] destroyed woods is implausible.”

“The dockyard had a wide, but by no means universal, impact on woodland,” he said.

A specialist in historical ecology at the University of Cambridge, he contended that the regenerative nature of trees and the meticulous manner in which British woodlands were managed actually carried them through the human onslaught.

“Since Rackham, the argument has been taken beyond the claim that cutting for ship timber did not cause deforestation, to the claim that shipbuilding had little or no effect on the landscape whatsoever,” Patrick Melby wrote in a 2012 Western Oregon University paper, Insatiable Shipyards: The Impact of the Royal Navy on the World’s Forests, 1200-1850.

He said Rackham’s findings are inconclusive, at best, and asserted that the historian’s claims “have been taken too far.” The period surveys Rackham relied on tended to be incomplete, said Melby, and he overestimated the trees’ regeneration rates, almost doubling the consensus figures.

Shipbuilding, Melby explained, demanded only specific species of trees and only small numbers of those species were removed from any one location at a time, preventing the clearing of whole forests for the sole purpose of shipbuilding.

“When examined in this light, it is easy to dismiss the concept of timber shortages,” he conceded. “Woods continued to exist through to the 19th century and continued to produce new growth.”

Access to timber suitable for shipbuilding was another matter, however.

“There was neither a sudden wood shortage brought on by shipbuilding demand, nor was the regenerative nature of trees able to cope entirely with the demands placed on woodlands by the Royal Navy,” Melby wrote.

“Instead, the rate of usage likely outpaced that of regeneration. There may not have been a universal wood shortage as Albion suggested, but consistent removal of great oaks for shipbuilding very likely stripped suitable oaks from the landscape more quickly than they could reproduce, causing a gradual, dispersed reduction in the quality and quantity of available timber.”

Admiral William Monson wrote at the time that English woods were “utterly decayed.”

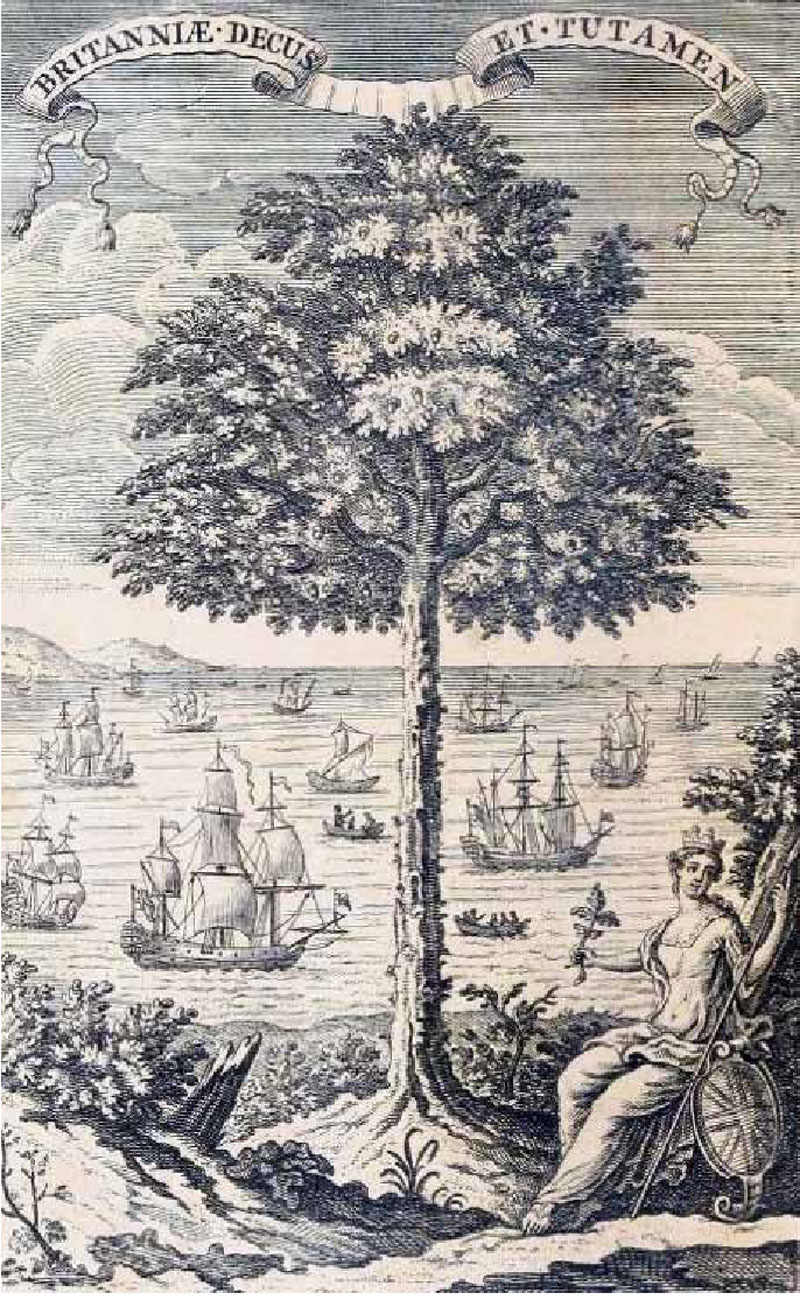

Melby even referenced period documents that note a decline in Britain’s ability to supply oak timber and its ever-increasing reliance on imports. He cited an 18th century illustration connecting British maritime power to timber oaks and promoting the nation’s woodlands as the “key to England’s future.”

The need was so great that the RN went far beyond the British Isles for suitable wood for its ships—to Scandinavia, the Baltics, Germany, Russia, even New England and what are now the Maritime provinces.

The wars and accompanying expansion of the Royal Navy in the 18th and 19th centuries, he pointed out, “represent not the start, but an intensification of demands on a habitually taxed system.”

A 18th century banner featuring a mature tree and naval ships declares “Britain’s Glory and Protection,” emphasizing the role the mighty oak played in Britain’s defence and empire. At the tree’s base sits Britannia holding an oak seedling. The illustration is believed to have been a propaganda piece promoting the replanting of oaks to assure Britain’s continuing strength as a maritime nation. [Perlin/A Forest Journey]

As early as the mid-1600s, British navy and other shipbuilding requirements had already grown so much that Sweden purchased control of the straits separating it from Denmark to ease access to its primary timber customer and reap the benefits of associated duties, taxes and shipping fees. Shipping wars inevitably festered, closing the straits briefly in 1654.

Admiral William Monson wrote at the time that English woods were “utterly decayed” and that Ireland’s were facing a similar fate.

By the late 18th century, the navy needed 50,000 loads of oak a year to keep its shipyards operating—almost a quarter of the country’s total requirements. Britain had begun building ships in its colonies, including the Caribbean, the Americas and India.

In 1801, Britain imported 1,186 masts from the Baltic region and another 198 from North America, but many of these were sub-standard, requiring builders to cobble together multiple sections bound at the joints with iron bands.

Newfound access to American white pine breathed new life into the shipbuilding industry, Melby said.

“The size, quality, and abundance of masts to come out of New England and Canada surpassed that found anywhere else, and they were added to domestic oak hulls, and topmasts and planking from the Ukraine, Poland, Norway and elsewhere to carry the Royal wooden fleet to its peak.”

Vast amounts of wood were also required to make the fires to fashion ships’ fittings. It took 50 cubic metres—the annual growth of about 10 hectares of northern European forest—to make a tonne of wrought iron using pre-1760 technologies.

The demands of naval stores became a key component of England’s foreign policy.

By the 18th century, the Crown was sending diplomats to the timber-rich Baltic countries to secure continuing availability of naval stores for England while simultaneously denying them to maritime enemies such as France.

Three armed conflicts erupted between 1800 and 1815 over the issue, in the midst of the Napoleonic Wars.

Melby believes that over time, the lack of suitable wood probably affected RN operations. And he says modern-day problems regenerating oak in Britain may in part be a result of historic woodland harvesting that affected soils and nutrients.

The effects of Britain’s campaign to build an empire and maintain it, he said, were felt far and wide.

“Beyond Britain’s borders, trade in masts, planking, oak, pitch, and tar demanded far more from woodland sources than were ever felt at home, and stretched the Royal Navy’s reach to diverse ecosystems around the world,” he wrote.

“As research continues, the full extent to which the construction of the wooden Royal Navy consumed both domestic and foreign woodlands must be recognized.”

Advertisement