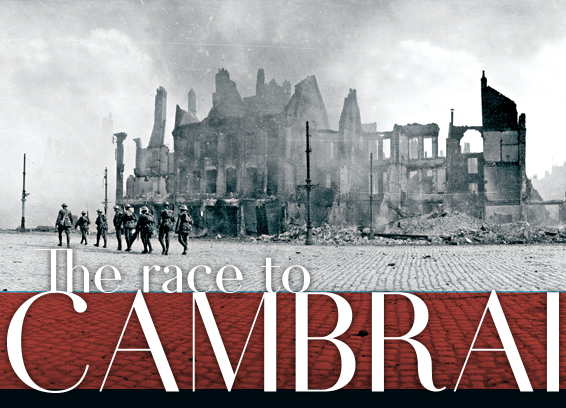

Canadian troops enter the main square of Cambrai, France, in October 1918, only to find that three sides of it have been set on fire by retreating German Forces. [William Rider-Rider/DND/LAC/PA-040229]

In September 1918, German-occupied Cambrai was on the verge of falling. But could the Canadians reach the town in time to save it?

A century ago, the provincial town of Cambrai, France, was a focal point of major military operations on the Western Front. It was a vital military railway and road hub that underpinned Germany’s four-year occupation of northern France. Thanks to its logistical importance, Cambrai received special attention from Allied bombers, even in the early months of the war. German commanders considered such raids harbingers of pending attacks in the sector.

It was the Germans’ “great distributing centre,” Canadian Corps Lieutenant-General Sir Arthur Currie noted in September 1918, and control of the sector hinged on its possession. The town was one of the keys to the Hindenburg Line, an important German defensive position about 16 kilometres away. It was also a key objective of the Allied offensives that drove the German armies gradually but decisively eastward in September and October 1918.

As recently as November and December 1917, Cambrai had been the focus of attention in an operation by the British Army best remembered for the mass employment of tanks, but was arguably more significant for the artillery plan used.

Rather than telegraph their intentions with a lengthy preliminary bombardment, which had become customary, the British saved the element of surprise through “silent registration”—in effect shooting from map measurements without preliminary ranging shots. The 1917 attack punched a substantial hole in the German front line, but the army had been unable to capture the vital high ground at Bourlon Wood and German reinforcements soon tipped the scale in favour of the defence, recovering much of the ground that had been lost—for the time being at least.

Canadians take stock of a captured ammunition dump just outside of Cambrai. [DND/LAC/PA-003397]

The Allied armies counterattacked in the summer of 1918, scoring major victories on the Marne in July and at Amiens in early August. The Canadian Corps spearheaded the Amiens offensive, then moved north to the Arras sector later in August. By the end of September, the Canadians were on the verge of crossing the partially completed Canal du Nord, one of a series of water obstacles that cut across the landscape around Cambrai.

The attack went in on the morning of Sept. 27. German forces in the sector fought with determination, making the advance difficult and costly. Still, Canadian troops rushed across dry segments of the canal, overrunning Bourlon Wood and the approaches to Cambrai. That night, German forces fell back all across the front; Ludendorff was convinced on Sept. 28 that the war was all but lost.

This mattered little to soldiers on the ground—Canadian, British or German—between the Canal du Nord and Cambrai. In the last days of September, the Canadian Corps continued its advance to the Marcoing Line, meeting stubborn resistance from German troops desperately trying to hold Cambrai. Despite its dire predicament, the German army remained effective at the tactical level, even launching fierce counterattacks against Canadian troops along the Cambrai-Douai road (see page 96). As in the trench warfare of 1916-17, the price of each metre was measured in blood. On Sept. 29 alone, the Canadian Corps suffered more than 2,000 casualties.

Among them was Canon F.G. Scott, the beloved chaplain of the 1st Canadian Division.

Artillery on the Canadian Corps front fired some 7,000 tonnes of ammunition. While it may have been little comfort for the hundreds of wounded Canadian soldiers or the loved ones left behind by the dead, the Germans were reaching their breaking point. Between Sept. 27 and Oct. 1, the Canadians captured 7,000 prisoners and more than 200 guns. And across the Western Front more generally, the German High Command madly shuttled broken divisions from sector to sector in a futile effort to shore up the crumbling lines. In the Canadian sector, Cambrai was on the verge of falling. But could the Canadians reach the town in time to save it?

Observers watch German troop movements near Cambrai in October 1918. [DND/LAC/PA-003245]

Meanwhile, the timing of the Canadian attack depended very much on the progress of neighbouring formations in Third Army. The army’s plan was arranged in two phases. First, Britain’s XVII Corps, which had fought alongside the Canadian Corps in earlier operations, was to capture the Niergnies-Awoingt Ridge southeast of Cambrai, while the Canadian Corps created a diversion through artillery fire.

In the second phase, the 2nd Canadian Division was to storm the Canal de l’Escaut between Ramillies and Morenchies, north of Cambrai, linking up with the British at Escaudœuvres, east of the town. The 3rd Canadian Division would then cross the canal and move on Cambrai itself.

The plan was fraught with risk. On the 2nd Division’s front, for example, the approaches to the canal were characterized by steep slopes on the west bank that would leave the infantry badly exposed to small arms and machine-gun fire from the east bank. Indeed, elements of the 3rd Division had been badly cut up a week earlier in an abortive attempt to breach the canal. The best chance was to go in at night, which Major-General H.E. Burstall, the 2nd Division’s commander, intended to do immediately after the Corps reached the Niergnies-Awoingt objective.

The Third Army attack began on the morning of Oct. 8 with initially encouraging reports. Later in the day, however, Canadian commanders learned that the XVII Corps attack was stalling short of its objective. Burstall decided to cross the canal and drive on to Escaudœuvres in any case.

In the pitch-black darkness on the night of Oct. 8-9, the soldiers of the 2nd Division crossed the canal under blustery rain showers. German troops, in the process of staging a withdrawal, were caught completely off guard. Ramillies fell, and Canadian patrols found neighbouring villages abandoned in the small hours of Oct. 9. Canadian engineers seized canal bridges intact and removed demolition charges before they could be exploded.

An engineer officer, Captain Coulson Norman Mitchell, and three of his men fought off a group of German soldiers who attempted to retake and destroy the main bridge at Pont d’Aire. Mitchell was decorated with the Victoria Cross for his role in the action. It was one of at least 10 Victoria Crosses awarded to Canadians fighting between Canal du Nord and Cambrai.

That morning, infantrymen of the 3rd Division entered Cambrai, finding the city largely deserted, with the exception of small German rearguards. The canal bridges in town were damaged, but the tireless engineers went to work installing new bridges that could handle wheeled transport and artillery.

As the Canadians advanced to the centre of town street by street, they found that German soldiers had indeed set some of the buildings alight, and were apparently in the process of starting additional fires, having left behind large stacks of combustibles in the wake of their hasty retreat. The engineers fought and extinguished the fires, saving the town from worse damage. Official photographers captured ghostly images of small parties of Canadian troops moving warily through empty streetscapes filled with smoky haze. Although badly hammered in some quarters, Cambrai was narrowly saved from complete ruin. If the attack had been a day or two later, the outcome may well have been very different.

While German forces failed to complete their destruction of Cambrai, the attempt was typical of a scorched-earth policy that characterized their eastward withdrawals during the final phase of the war. As one Canadian soldier wrote home that October, the enemy “has taken everything he could have…. He has done his best to stop us by blowing up all the main roads, bridges, etc. and what he could not take that would be of value to us he has destroyed. Stacks of hay were still smoldering and all the mines…were damaged as much as possible.”

The destruction of roads and bridges might be justified on tactical grounds, but there was also something clearly senseless about it all, given that the German High Command had already admitted to itself, and to the Kaiser, that the war was lost.

Canadian soldiers pass through ruined buildings as they enter Cambrai. [DND/LAC/PA-003286]

At the beginning of August, the Canadian Corps had been built up to something near full strength, ready for action like a coiled spring. The two months between the Battle of Amiens and the liberation of Cambrai witnessed a virtually unprecedented pace of operations.

Between Aug. 22 and Oct. 11, the Canadian Corps sustained 1,544 officers and 29,262 other ranks killed, wounded or missing—nearly one-third of the corps’ overall strength, but a much higher proportion of its infantry strength. In exchange, the Canadians claimed more than 18,000 prisoners, 371 guns, nearly 2,000 machine guns, and an unknown number of enemy troops killed or wounded fromat least 30 German divisions.

Earlier campaigns, such as Vimy/Arras, had seen higher numbers of Canadian casualties per day of battle, but the sustained operations of August to October 1918 depleted infantry battalions at steady rates over an extended period. In this respect, the fighting between the Canal du Nord and Cambrai sheds valuable light on one of the most controversial elements of Canada’s war effort: the 1917 Military Service Act, and the impact of compulsory military service on the Canadian war effort during the closing months of the conflict on the Western Front.

The dominant historical narrative of the Military Service Act has long suggested that conscription was, effectively, a failed policy, as Patrick M. Dennis underscores in his recent landmark study Reluctant Warriors: Canadian Conscripts and the Great War.

Prominent historical commentators have doubted, for example, that the practical military results of conscription justified the staggering social, cultural and regional fault lines that the act forced open across Canada. Others, including such contemporary supporters of conscription as Currie himself, suggested that conscripts played a minimal role in the final stages of the war simply because they were too few and too late to reach the front.

There had been talk of conscription in Canada for some time, but the breaking point came with the Vimy/Arras offensive in the spring of 1917. Canadian casualties reached 24,000 killed and wounded in April and May 1917, yet fewer than half this number of men had volunteered for overseas service in the same period. Canada could no longer rely on voluntary enlistments alone to sustain its overseas military effort. In May 1917, Prime Minister Robert Borden asked Solicitor General Arthur Meighen to draft a military service act.

The initial recruiting target under the act was 100,000 men. As of November 1918, some 99,600 men had been taken on strength, and 47,500 of them had reached the United Kingdom. Only about half of these latter men—some 24,000—actually crossed over from the U.K. to join the firing line before the Armistice.

Two members of the 75th Battalion and their prisoner relax at a milestone near Cambrai. [DND/LAC/PA-003268]

After all, the number seems a relatively small proportion of the 99,600 recruits who were conscripted in late 1917 and 1918, not to mention the nearly 620,000 men and women (conscripts included) who enlisted in the CEF throughout the entire war. Round numbers, however, can be deceiving. It is instructive to consider that of 620,000 enlistees, 425,000 served overseas, and of these, just 345,000 served in France and Belgium. From that 345,000, about 236,000 passed through the 50 Canadian infantry battalions that fought at the front. Twenty-four thousand conscripts comprised a small proportion of 236,000 fighting men. But given that the nominal establishment of the Canadian Corps in 1918 was about 100,000 men (approximately 48,000 of whom were infantrymen) and nearly all conscripts were assigned to infantry battalions, the 24,000 reinforcements raised through conscription assume rather greater significance.

During the final 100 days of the war, the Canadian Corps sustained some 45,000 casualties, a figure approaching nearly its entire nominal infantry strength! Reinforcement by conscripts in the 24,000 range was, consequently, vital under the circumstances.

The importance of Canadian conscripts at Canal du Nord and Cambrai, and throughout the final 100 days, is evident as much anecdotally as it is statistically. Private Norman Markle of Hamilton, Ont., was among seven conscripts counted among the 44 other ranks of the 102nd Battalion killed in action at Bourlon Wood. Markle’s older brother Walter, also a conscript, had died of illness earlier that year.

In fighting just north of Cambrai around Abancourt on Oct. 1, Pte. Leo Dennis of the 1st Battalion was killed, likely a victim of friendly artillery fire. Dennis, from Windsor, Ont., had been drafted on the same day as his neighbour, Walter Campeau, who was also killed in the battle.

Many more conscripts fell at Cambrai. One of them was Pte. Polide Aucoin, a farmer from Cape Breton Island who served with the 25th Battalion. Pte. Raymond Dujay, a sailor from Amherst, N.S., was another of four conscripts from the 25th Battalion to die in the Cambrai attack on Oct. 9.

Hundreds of such cases are found in Dennis’s Reluctant Warriors. The point is clear: conscripts were instrumental to Canadian operations during the final 100 days, and they paid dearly alongside their volunteer comrades.

The war was nearly over on Oct. 9, although few could have guessed that the guns would fall silent in the West just one month later. Sadly, the end did not come soon enough for the thousands of men who were killed or wounded in the final weeks.

The final stretch of the road to victory led the Canadians to Valenciennes, and then on to Mons, Belgium, where British and German troops first fought more than four years earlier.

The last Canadian (and British Empire) soldier known to have died in action, Pte. George Price is buried outside Mons at St. Symphorien Military Cemetery. Buried there also is Pte. John Parr, thought to be the first British soldier to die in action on the Western Front. Parr was a prewar regular soldier. Price was a conscript. So much had changed in four years.

Tanks are loaded on railway cars following the Armistice. [Wikimedia]

Tanks at Canal du Nord and Cambrai

Since their operational debut in the Battle of Flers-Courcelette in September 1916, tanks had become increasingly common, if not ubiquitous, sights in the battle zone. The British and French armies each fielded a series of designs, with increasing emphasis on lighter, faster vehicles by 1918. In Germany, a heavily bureaucratized design project spawned the monstrous A7V tank, albeit too late in the war to matter. Only about 20 were built, with the Germans making relatively greater use of captured Allied machines (although never more than about 90 at any one time).

Arguably the most famous British tank operation of the war was the 1917 Battle of Cambrai, where despite impressive initial gains, the armour was eventually driven back. Tanks returned to support the Canadians at Canal du Nord, Bourlon Wood and Cambrai in 1918. The Germans had hoped that the dry portion of the canal bed would present an impassable obstacle to enemy armour, but this was not the case. British tanks crossed the canal near Mœuvres, close to the boundary between the Canadian Corps and XVII Corps. Four tanks came to the aid of the 3rd Canadian Brigade at Sains-lès-Marquion, crashing through barbed-wire aprons and mopping up enemy holdouts in the village. The armour also played a role in clearing Marquion, along with kilted infantry from the 13th and 15th battalions.

The 7th Tank Battalion, which had seen terrible fighting at Bourlon Wood in 1917, was back in action at the same spot, supporting Canadian infantry in Bourlon village and helping to clear out the wood. This time there would be no British withdrawal. However, of 16 tanks supporting the Canadians at this stage of the advance, five were put out of action by German anti-tank fire, which was generally effective.

Immediately after the liberation of Cambrai, the Canadian Corps pressed northeast to Iwuy, with armoured cars and cavalry in the vanguard. The mobile units were badly shot up by German rearguards, and the A7V tanks appeared at the village. Corporal Deward Barnes of the 19th Battalion remembered some panic at the sight of such large machines, but they were soon dealt with by concentrated artillery fire.

Advertisement