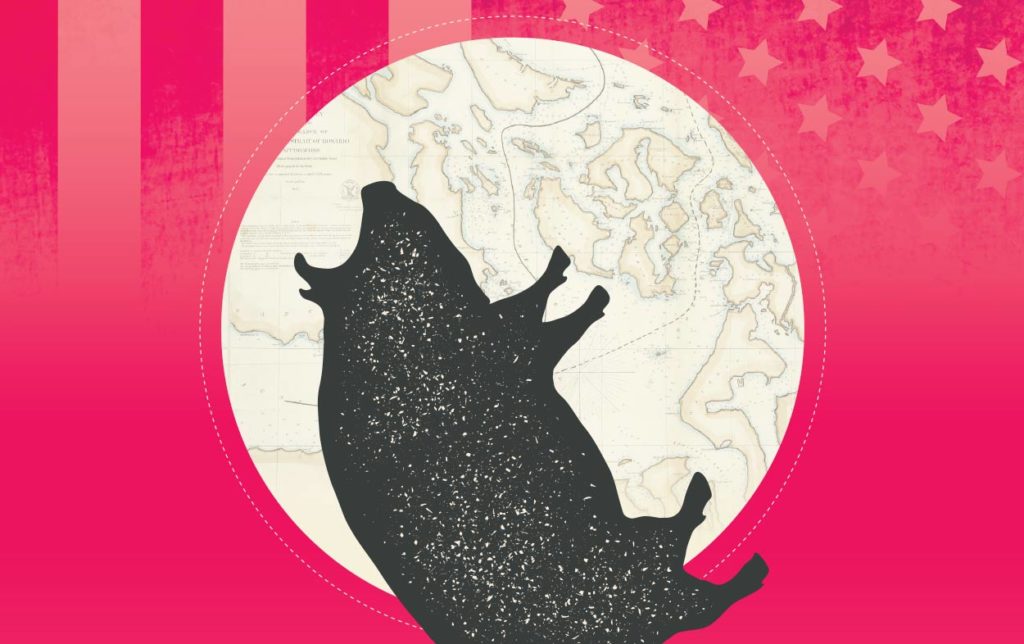

War was narrowly averted between the British Empire and the United States in 1859 over the killing of…a pig. It occurred on San Juan Island, about 12 kilometres east of Vancouver Island.

There was no shortage of bad blood between the U.S. and the British Empire in the 19th century. And the British colonies in present-day Canada were often caught in the middle—and always a potential battleground. A war started over the slaughter of swine would have ranked as one of the more absurd conflicts in history, but it could still have taken the lives of countless soldiers, sailors and civilians.

The confrontation was charged with historical grievances and expansionist urges, made worse by reckless adventurism and misplaced notions of honour. It eventually calmed through cool military professionalism. The Pig War, as it came to be known, is a reminder that fragile peace can always be broken by the acts of a few impulsive glory seekers.

Bad neighbours

Britain and the U.S. carried deep wounds from the American Revolution, which were scratched raw by the War of 1812. While peace treaties reduced the chance of another war, there were several minor conflicts between the U.S. and British North America in the 1830s. While the political and military leaders in Washington and London did not want a war, a war might still find them.

The U.S. had grown steadily in power, population and size, expanding with fervour and systematically driving Europeans from its territory throughout the first half of the 19th century. Many Americans were motivated by the idea of manifest destiny, a term coined in the 1840s to describe the spread of American exceptionalism, show the world the power of democracy and merge all of North America into the U.S.

As part of this march, the U.S. waged wars against Indigenous Peoples, and annexed Texas, California and large parts of Mexico. With the U.S. having expanded southward and across the continent to the Pacific, the northern border with the British Empire became a vexing situation for many Yankee politicians, soldiers and expansionists.

Rivals

After the 49th parallel was agreed to as a border between British North America and the U.S. from Lake of the Woods to the Rocky Mountains in 1818, there were only a few contentious geographical spaces left to be surveyed. The largest such swath of land was the area west of the Rockies, stretching from the southern border of present-day Oregon to present-day Yukon. The area had been jointly occupied by Britain and the U.S. since the early 19th century, with no agreement on where the border lay. The key sticking point was the Strait of Juan de Fuca, home to some 100 islands between the mainland and Vancouver Island.

In what is now British Columbia, the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) was the power on the northern side of the 49th parallel, along with Indigenous Peoples whose lands the Europeans were slowly making their home through treaty, displacement and war.

As several thousand Americans filtered into the Pacific northwest by the early 1840s, the region became a point of potential conflict. The 1846 Oregon Treaty helped relieve some of the pressure, though. It established the border from the Rockies to the West Coast along the 49th, with the exclusion of Vancouver Island. But the agreement included ambiguous language about the Gulf of Georgia, or the “de Fuca’s Straits” as it was called. Most problematic, it did not delineate the water border between Vancouver Island and the American mainland to the east.

The few accurate maps of the time showed three possible routes through the waterway. The Rosario Strait was nearest the American territory, the Haro Strait was closer to Vancouver Island, and a third route passed to the east of San Juan Island and between Lopez and the Orcas Island. With these three channels through the straits, where would the border be established? And would the islands be British or American? With no agreement, the boundary decision was put on hold.

As additional attempts to establish a boundary failed, British Captain James Prevost wrote in 1856 that the loss of San Juan Island could “prove fatal to Her Majesty’s Possessions in this quarter of the Globe.” Both the British and Americans saw possession of the islands as strategically advantageous to protect against invasion—or to launch an attack.

Cutlar came upon a lone hog rooting in his garden. Enough was enough.

He shot it dead.

The experienced, canny and ruthless James Douglas was the British leader in the area. He had worked his way up through the ranks of the HBC, was appointed governor of the Colony of Vancouver Island in 1851 and, in 1858, also became governor of the Colony of British Columbia. He was wary of the Americans in the region—people “of a class hostile to British interests”—and, beginning in the early 1850s, he encouraged British settlement of islands in the Gulf of Georgia with land grants, believing that occupation would strengthen future boundary negotiations.

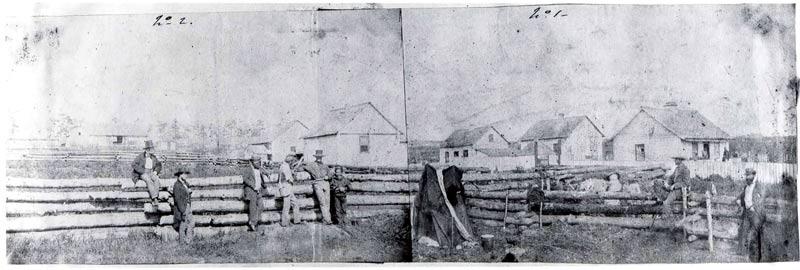

At the time, there were only a few dozen Americans and Brits on San Juan, together with several thousand sheep, cattle and pigs. An HBC sheep farm was the primary British claim on the island in the early 1850s. However, after the discovery of gold in the Fraser River region in 1857, thousands of American prospectors flocked to the area, bringing prosperity—and chaos. The rowdy miners only confirmed and deepened Douglas’ anti-Americanism.

The death of a pig

An American gold seeker, Lyman Cutlar, was the man who nearly started the Pig War. After failing to find his fortune in B.C., the Kentucky frontiersman drifted south to try his hand at farming on San Juan Island. The British representatives on the island kept an eye on him and the other small bands of American farmers.

While Cutlar found some success in farming, several animals owned by the HBC—notably wandering pigs—took to eating his vegetables. Cutlar repeatedly chased the animals off, but on a warm June 15, 1859, Cutlar came upon a lone hog rooting in his garden. Enough was enough. He shot it dead.

Cutlar had immediate regrets. Aware he may have crossed a line, he walked to the local HBC authority, Charles Griffin, and confessed to having killed the animal. After justifying his actions, he offered to pay for the pig. Griffin, who had been marooned on the island for some time and perhaps seething at his lowly position, flew into a rage.

Cutlar was threatened with eviction. And, while the pig was worth about $10, the HBC man demanded $100 for it. Cutlar, now equally angered, stalked off, refusing to pay a penny for the slain swine.

Fired up over the slight and carrying anti-American grievances, a party of British men converged on Cutlar’s farm demanding retribution. The American stood firm, backed by his rifle. Who had authority? If the island was British, he could be arrested, with one HBC man describing Cutlar as a “lawless intruder.” If it was American territory, however, the HBC had no jurisdiction. What laws applied? They were at a standstill.

Escalation

The situation intensified when Brigadier-General William S. Harney, then in command of the Department of Oregon (the U.S. army division overseeing the area), got involved. He was known as a hothead with hair-trigger anger who had brutally slaughtered Oceti Sakowin (Sioux) during one battle. Even in the rough and tumble American army, Harney stood out for having been court-martialed four times, usually for acting rashly and wrongly. Adding to this potent and unstable mix, Harney was a vocal hater of the British. He was the wrong man to keep things cool.

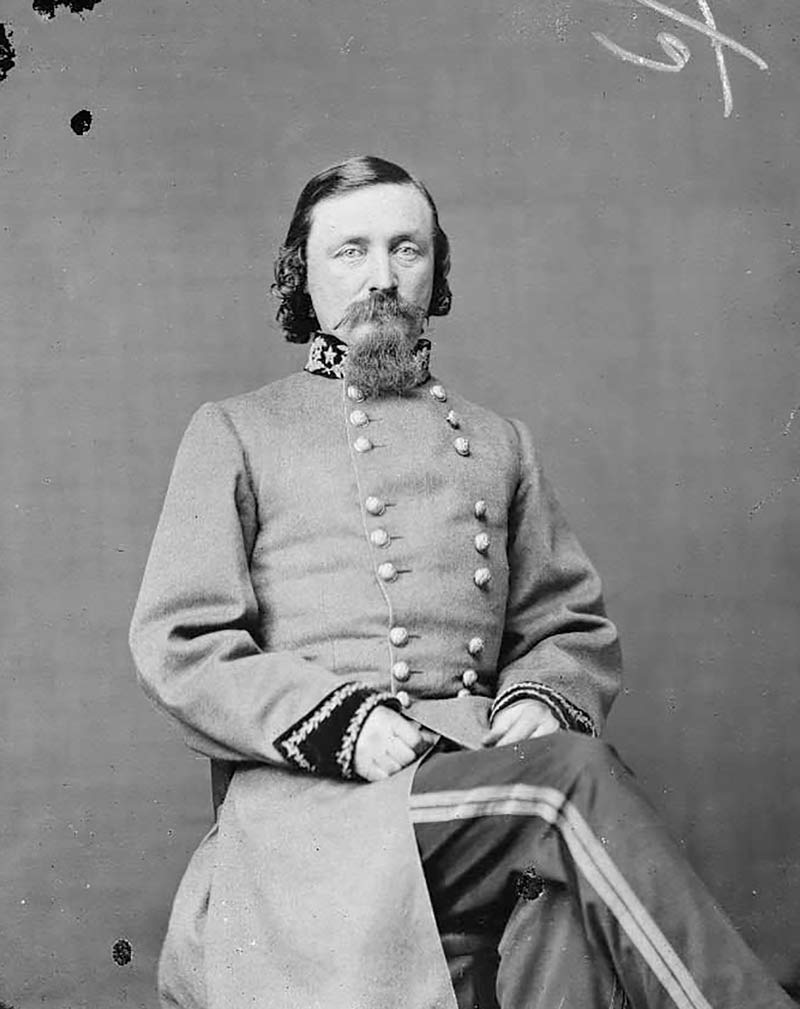

Harney ordered a small detachment of soldiers to the island in mid-July 1859. Captain George Edward Pickett, then a largely unknown soldier who later became famous for his Confederate charge at the Battle of Gettysburg during the American Civil War, would lead it.

The arrival of Pickett’s garrison of 60-plus soldiers near the HBC sheep farm on July 27 was a worrisome challenge to the British, made all the worse by Pickett’s order that only U.S. law would be recognized on the island. This led to much anger in B.C., where the colonists felt the Americans were bullying the HBC farmers and slighting British honour. Governor Douglas asked the Royal Navy to uphold British rights and sovereignty. He was spoiling for a fight.

William Peck, an American army engineer stationed on the island, wrote, “[it] is feared a collision will occur.”

A tense standoff ensued as the Royal Navy considered blowing them out of the water.

Confrontation

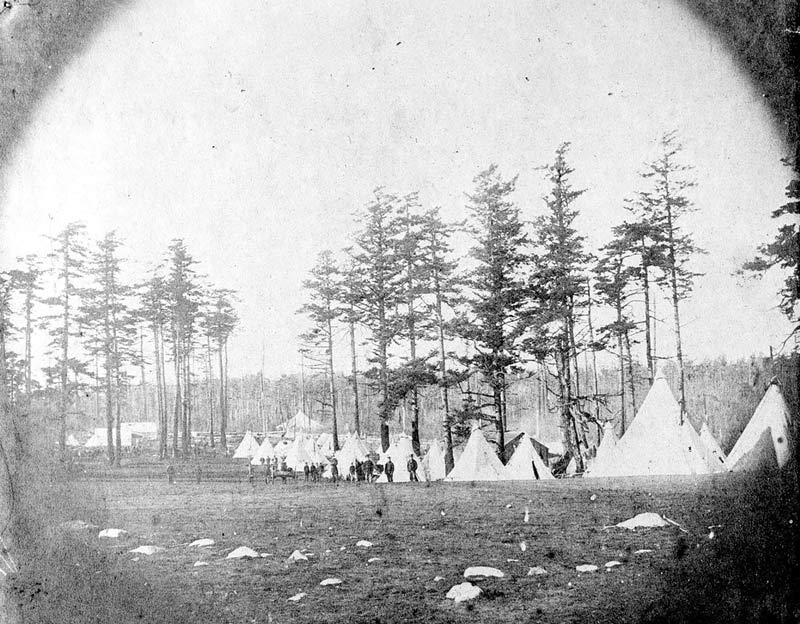

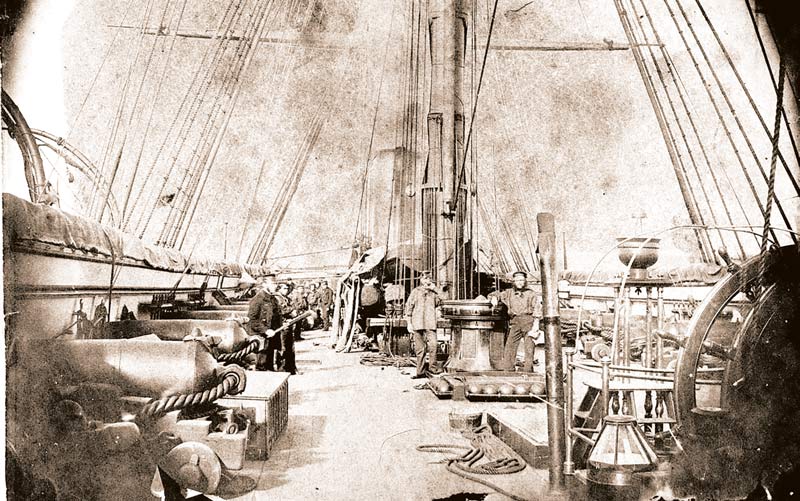

The Royal Navy’s HMS Tribune, a 31-gun 2,000-ton steam frigate, and HMS Satellite, armed with 21 guns, arrived off San Juan in a show of force at the end of July. Soon the warships had their many cannons directed on Pickett’s encampment, which he had ill-advisedly laid out in full view.

While colonists in B.C. demanded retribution for the American actions, noting the Yanks needed to be taught a lesson, the senior Royal Navy commander, Captain Michael de Courcy, told Douglas he did not seek a battle, even though British sailors and mariners vastly outnumbered the Americans.

As the outgunned Pickett scrambled to move his camp and dig in, the swaggering Harney remained belligerent. On Aug. 1, more American reinforcements arrived by ship. A tense standoff ensued as the Royal Navy considered blowing them out of the water.

Instead, the British again responded with restraint and allowed another hundred-plus Americans to go ashore unimpeded, though several additional British warships arrived, for a total force of five vessels and more than 1,000 soldiers and marines. Facing total naval dominance, Pickett observed: “They have a force so much superior to mine that it will be merely a mouthful to them.”

While neither the American nor British governments wanted war, much was left to the soldiers and sailors on the spot. There was a long history of American filibusters starting local wars and dragging the nation into conflict. San Juan might be another battle started by irresponsible soldiers seeking glory.

Washington reacts

The slow movement of news also contributed to the potential conflict. It took about a month for messages to travel from San Juan to Washington and about six weeks for communiques to reach London. And, so, the crisis of early August 1859 only reached the two capitals in September.

The cabinet of President James Buchanan was fearful of a war with Britain, especially with tension mounting between northern and southern states over slavery, which had already led to terrible bloodshed.

While both the British and American press were quick to howl for a restoration of honour and a comeuppance for the opponent, the Buchanan cabinet was alarmed at the potential war. It ordered its greatest soldier to the far-flung corner of the country, hoping that the commander of the U.S. army, Winfield Scott, a hero of the Mexican War, would bring much-needed expertise (also see “The great Pig War pacificator,” right). Harney blanched at the idea of Scott’s arrival because the two had a long and difficult history that included Scott having once court-martialed Harney for insubordination.

After a month of travel, Scott arrived on the Columbia River on Oct. 20, 1859, where he met the governor of the Oregon Territory and General Harney. News of his diplomatic voyage had reached the Americans, Royal Navy officers and British colonials beforehand, and there was new hope the general might find a compromise.

Compromise

Governor Douglas and Lieutenant-General Scott conferred and after negotiations, most of Pickett’s soldiers were removed from the island by the end of November, just as some of the British warships pulled back to Esquimalt. Common sense prevailed and the showdown de-escalated. San Juan would return to being jointly occupied, with an urging for diplomats and surveyors to tackle the boundary issue—with compass and map rather than rifle and cannon.

Scott exited the region on Nov. 11, 1859, surprisingly leaving Harney in command (although on his long trip home, he laid plans to have him transferred to another front where he could cause less harm). Still, the area remained a powder keg. Even after the compromise, the long delay in communication led London to call for a remilitarization of the island. This, too, might have led to war.

The senior British naval officer, Rear Admiral Robert Baynes, a veteran of the 1815 Battle of New Orleans and commander of the 84-gun ship HMS Ganges, sensibly refused the order, and kept the peace through less confrontational acts. Baynes told Governor Douglas that he would not “involve two great nations in a war over a squabble about a pig.”

The Americans, meanwhile, continued to stir up trouble, with General Harney ordering Pickett back to the island. Some thought Harney ached for a war in hopes of kickstarting a political career. Whatever the case, this move caused a new round of grievance, but fortunately, not the same level of threat.

Eventually two small garrisons, one British and one American, were stationed on the island. And the San Juan rift was overtaken by southern U.S. states seceding from the Union to form the Confederate States, and eventually starting the U.S. Civil War.

Rear Admiral Baynes received a knighthood in April 1860 for his long service and “good sense and prudence” in the Pig War. General Harney was sidelined during the Civil War, but had a surprising role in aiding several Indigenous nations negotiate treaties with the U.S. in the 1860s.

Resolution

When the Union and the secessionist South went to war in April 1861, Britain studied its options. It might support the South to weaken the North, and it certainly needed Southern cotton for its factories. But there were few politicians in London who wished to support the odious slave system. Britain and the colonies of British North America decided to remain neutral, although they were nearly dragged into war on several occasions. The war did compel Canadians to think more seriously about their security, a key factor in driving the colonies toward Confederation in 1867.

But what of San Juan and the possibility of future assassinated pigs leading to war between Canada, Britain and the U.S.? After the 1871 Treaty of Washington settled many of the differences that arose from the Civil War, the Americans and British (who continued to conduct foreign affairs for the young Dominion of Canada) submitted their duelling claims over San Juan to German Kaiser Wilhelm I the following year. The Kaiser had unified the German states through blood and iron, and now the conquerer became the judge. After experts studied maps and heard arguments, the Kaiser awarded San Juan Island to the U.S. in October 1872, with the boundary passing through Haro Strait.

The slain swine had long been forgotten, the only casualty in this imbroglio. But its death was a warning of the fragility of peace. The San Juan conflict was also a cautionary tale of how rogue soldiers and irresponsible adventurers can drag countries into war. It was a lesson, too, in how calm, professional and prescient men of war, in this case Admiral Baynes and General Scott, could avoid unnecessary conflict.

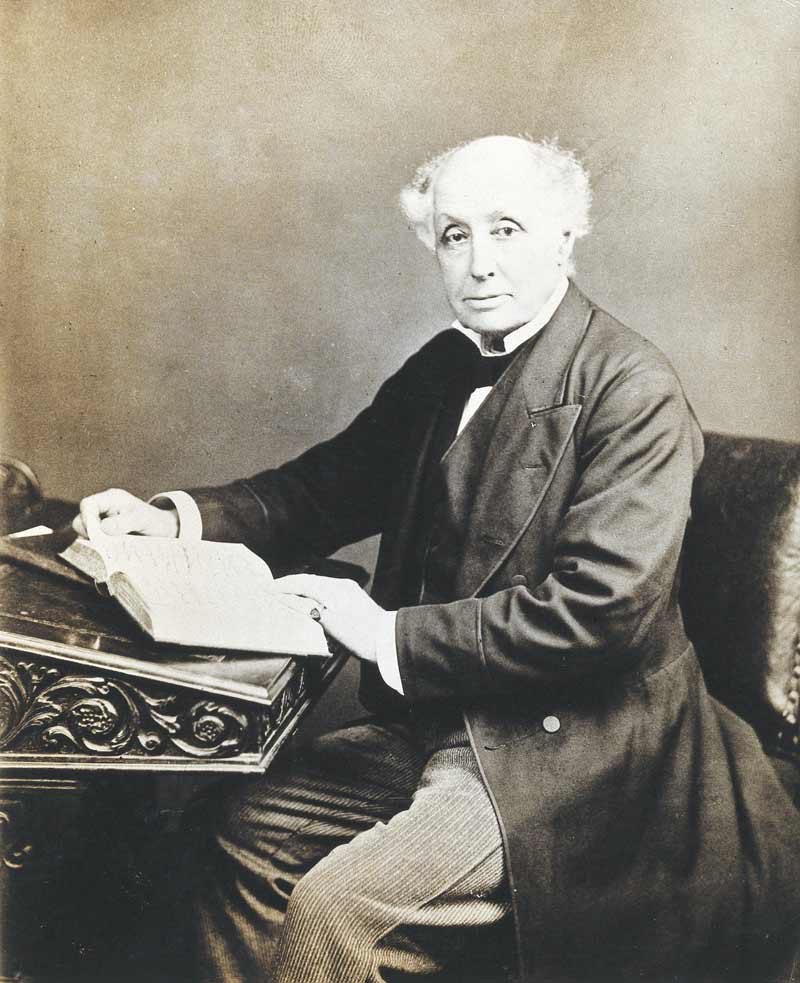

The great Pig War pacificator

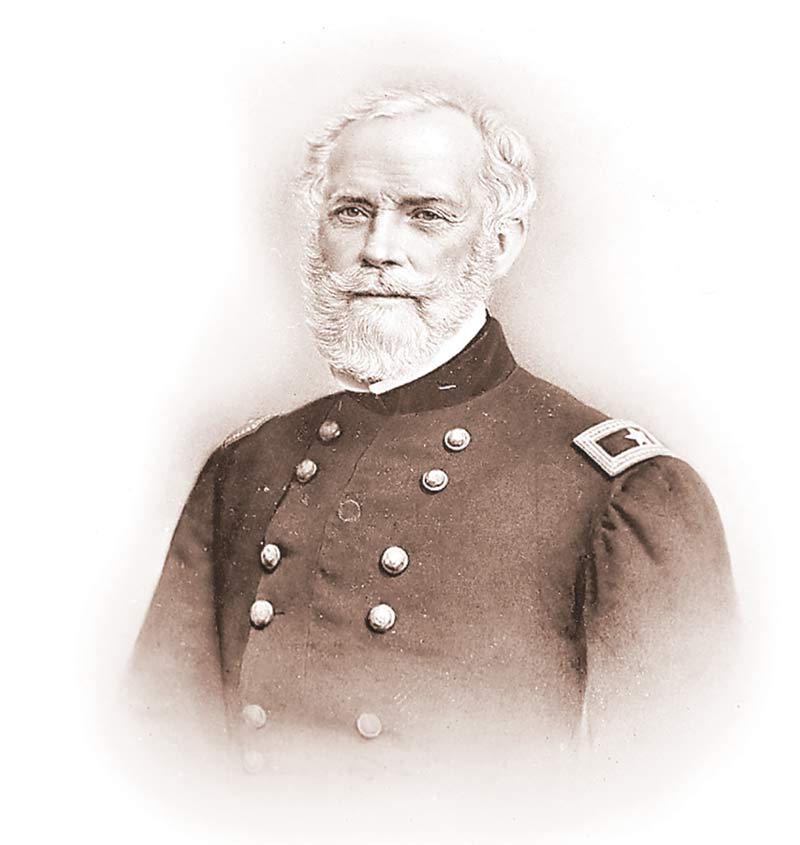

A veteran of the War of 1812, Major-General Winfield Scott played a key role in training the ragtag American army after its early humiliating defeats at the hands of Indigenous warriors, British and Canadian soldiers. Scott emerged from the war as a hero.

In 1838, Scott was again rushed to the Canadian border to ensure that rebel-supporting Americans did not provoke a war. After tremendous success on the battlefield during the Mexican War (1846-48), Scott continued to serve in many capacities, remaining popular with American soldiers who affectionately called him “Old Fuss and Feathers.”

By the Pig War of 1859, he was the foremost American general of his generation, holding the rank of lieutenant-general and enjoying the moniker of the “Great Pacificator.” There was no better person to send to the Pacific northwest, even though he was in poor health, grossly overweight and 73 years of age. There would be no going hog wild on his watch.

Advertisement