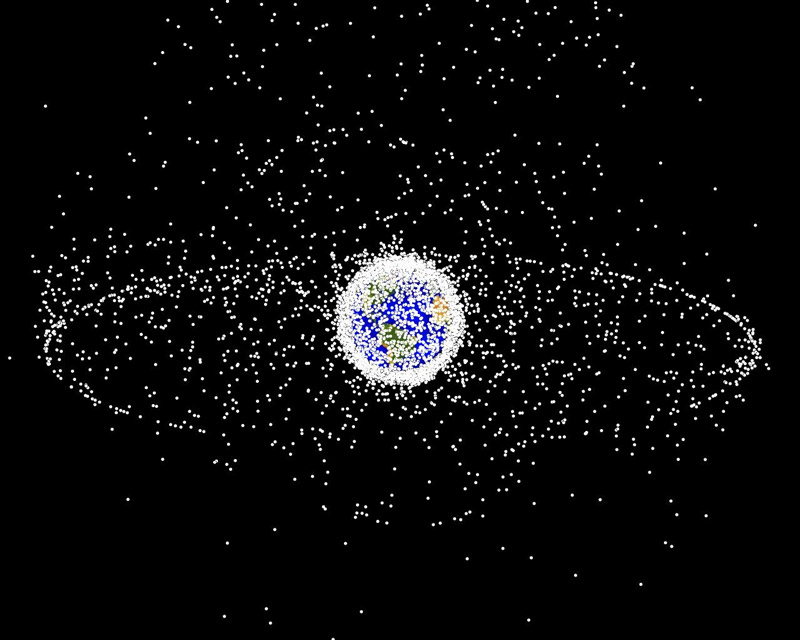

A computer-generated image represents space debris as could be seen from high Earth orbit. [Wikipedia]

The head of United States space operations is seeking new ways to manage the traffic jam of satellites and space junk crowding the skies over Earth—and to prevent fender-benders and extraterrestrial road rage in the process.

“The space domain…has become congested, contested and competitive.”

Speaking at this year’s virtual Ottawa Conference on Security and Defence, Lieutenant General Stephen Whiting, commander of Space Operations Command, said humankind is entering “a second golden age of space” but, like all things human, it brings unwanted baggage along with it.

“The space domain…has become congested, contested and competitive,” said Whiting, whose command is part of a new branch of the U.S. military with its sights focused on the great beyond.

He told his online audience that the U.S., Canada and their allies are keeping their collective eye on some 30,000 pieces of debris and other objects in orbit around the Earth, and he described escalating interactions between rival satellites that demand a more co-ordinated defence among like-minded nations.

“The number of active satellites is literally booming,” he said. “From 2019 to 2020, the number of payloads launched increased by almost 300 per cent, from just over 400 payloads in calendar year ’19 to over 1,200 payloads in calendar year ’20.

“Additionally, the average number of payloads on each launch increased from just over four payloads per launch in 2019 to almost 12 payloads per launch in 2020.”

It’s a new space race, as rival countries clamour to gain dominance over the high ground and all the opportunities—both commercial and military—that come with it. Elon Musk’s SpaceX only started launching satellites in earnest in 2019 and already owns almost a quarter of all active satellites in orbit, with more coming.

While space is more congested, Whiting said, it is also becoming more contested. In their strident efforts to get ahead of the game, he said “the irresponsible acts of other countries” are forcing allies to shift their focus to safety and mobility beyond the gravitational and atmospheric bounds of the planet.

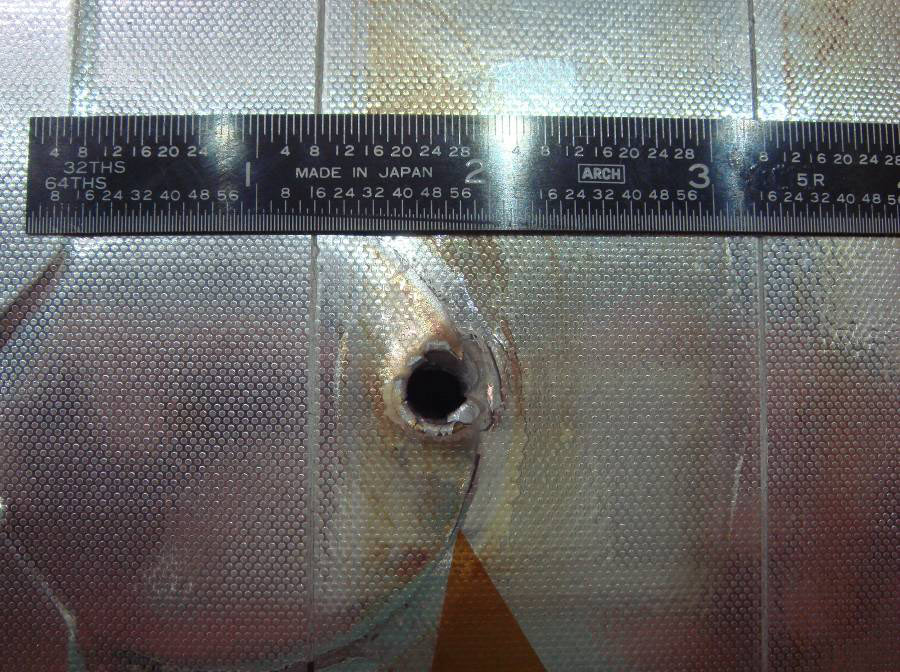

A radiator on Space Shuttle Endeavour was impacted by debris during during its 2007 mission to the International Space Station. The entry hole is about 5.5 millimetres and the exit hole is twice as large. [NASA]

“It appears aggressive, and it is definitely intentional.”

Whiting even described cat-and-mouse games among satellites in space looking to gain the upper hand or monitor the activities of others.

In 2019, Russia launched Cosmos 2542 into an orbital plane “specifically designed to be close to” U.S.A. 245, an American government-owned satellite.

“This is roughly equivalent to a Russian MiG intentionally getting on the ‘six’—or the aft tail, as we say—of an American or Canadian aircraft,” said Whiting. “It appears aggressive, and it is definitely intentional.

“Then, within a couple of weeks of launch, the Russian satellite burped out another satellite. And, when we manoeuvred U.S.A. 245 to create room between ours and the Russian satellite, Cosmos 2542 also maneuvered to maintain its position.

“This is not the responsible and safe behaviour we would want to see in space.”

The Pentagon stood up the U.S. Space Command two years ago to conduct military operations in space, as well as the U.S. Space Force, a sixth military service to organize, train and equip space forces—“guardians,” they’re called—to conduct a range of missions.

Operation Olympic Defender is a coalition of allied space-faring nations, including Canada, that aim to work together to deter hostile acts in space.

“Space underpins our economy, safety and our way of life,” said Whiting, referencing the words of his boss, the chief of U.S. space operations, General Jay Raymond. “It underpins every instrument of our national power.

“Space capabilities are a foundational infrastructure for modern life. We simply wouldn’t have the world we live in today or the world we want for tomorrow without those space capabilities.”

Space capabilities, he added, fuel economies and are critical to scientific advancement and national security. They enable scientists to effectively track climate change and facilitate communication to address the COVID-19 pandemic.

Speaking on a panel with the general was Michael Greenley, CEO of MDA, a Canadian aerospace technology company that provides intelligence, satellite systems, robotics and space operations.

He suggested a space system like the one that monitors the movements of ships at sea may help sort out the orbital mess and keep rivals at a distance—using satellite-borne transponders that would automatically identify objects and their locations.

Dan Goldberg, president and CEO of Telesat Canada, said governments and commercial operators have for decades operated under a common set of rules and understandings about space operations.

“But the reality is, they only get you so far,” said Goldberg. “At the end of the day, we are dealing with sovereign states. There really isn’t a great enforcement mechanism if you have a country that’s flouting the rules.

“We’ve seen that over the decades. At the end of the day, there’s not that much that can be done to bring them into compliance…with the rules. What you hope for is a recognition that space is there for all of us to use.”

The annual Ottawa Conference on Security and Defence is presented by the Conference of Defence Associations Institute.

Advertisement