Pioneer: Helen Harrison (right) was chief flying instructor at the Sheffield Flying Club in England, 1939. [Helen Marcelle Harrison Bristol/LAC/C-058286]

Women in Canadian

military aviation

Whiplash is how they described it. In 1980, when captains Nora Bottomley, Deanna (Dee) Brasseur and Leah Mosher walked anywhere in their Canadian air force blue flight suits, heads snapped around. The three women were the first in the country to receive their wings for active duty, and they knew they were under the microscope from their fellow pilots, superiors, the media and Canadian society. As Major Brasseur said later of that time, “If one of us burped, Ottawa knew.”

They were part of a five-year trial program called SWINTER (Service Women in Non-Traditional Roles) launched in 1979 to gather information and assess the effectiveness of mixed gender operational units. The trial, Brasseur noted wryly, “was not whether women could fly but whether the men could accept us.”

The air force—and the rest of society—should have had no doubt that women could equal their male counterparts as aircrew, ground support and “total war” aviation workers. After all, they had been licensed as civil pilots in Canada since 1928 and worked as nurses on the front lines since the days of the Northwest Rebellion in 1885. But little had changed since Alan Sullivan published Aviation in Canada, 1917-1918, just after the Great War. The perceived challenges were an exact echo from then: women would be too expensive to uniform and accommodate, too much trouble to integrate. History had proven, however, that when given the opportunity, women were exactly as good and as bad as men.

A young welder works at the Bren gun plant in Toronto, 1942. Posters recruited women to the RCAF WD. [NFB/LAC/C-007481]

Few Canadians of either gender were pilots when war broke out in 1914. Canada’s first powered flight, after all, had just occurred over the ice of Baddeck Bay in Nova Scotia five years earlier. So it is not surprising that women’s first contact with military aviation was at the munitions factories of Central Canada. About 2,000 of these young, single, mostly working-class women were happy to find any work during the economic recession that lasted until 1916—even if the working conditions could be harsh and the hours long.

During the last half of the war, women finally had a chance to work for the Royal Air Force (RAF), which operated a training program in Canada. When there was a shortage of male labour, the RAF recruited 1,200 “patriotic women” as civilian workers, mostly in clerical positions, but also as transport drivers and mechanics. Sullivan wrote in 1919 that women “might have been seen in any of the shops or camps, dressed in dusters, caps and overalls, taking down engines, grinding valves, stripping aeroplanes and doing all forms of manual labour.”

The seed was also planted in May 1918 for a Canadian-based Women’s RAF along the lines of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) in Britain, but when estimates had women’s barracks costing twice that of men’s because they would have to construct separate facilities for eating, sleeping and “ablutions,” they dropped the idea. The Canadian public did not seem to catch wind of this cancelled scheme, but when the world was at war again in 1939, many more women were listening for the call. By then, Canadians had been exposed to the barnstormers and legendary bush pilots, and more women were joining flying clubs to get their pilot licences—even though they knew few opportunities existed to use them professionally.

But these women were disappointed in their military flying aspirations. As they watched Britain set up its auxiliary services, they hoped Canada would follow suit.

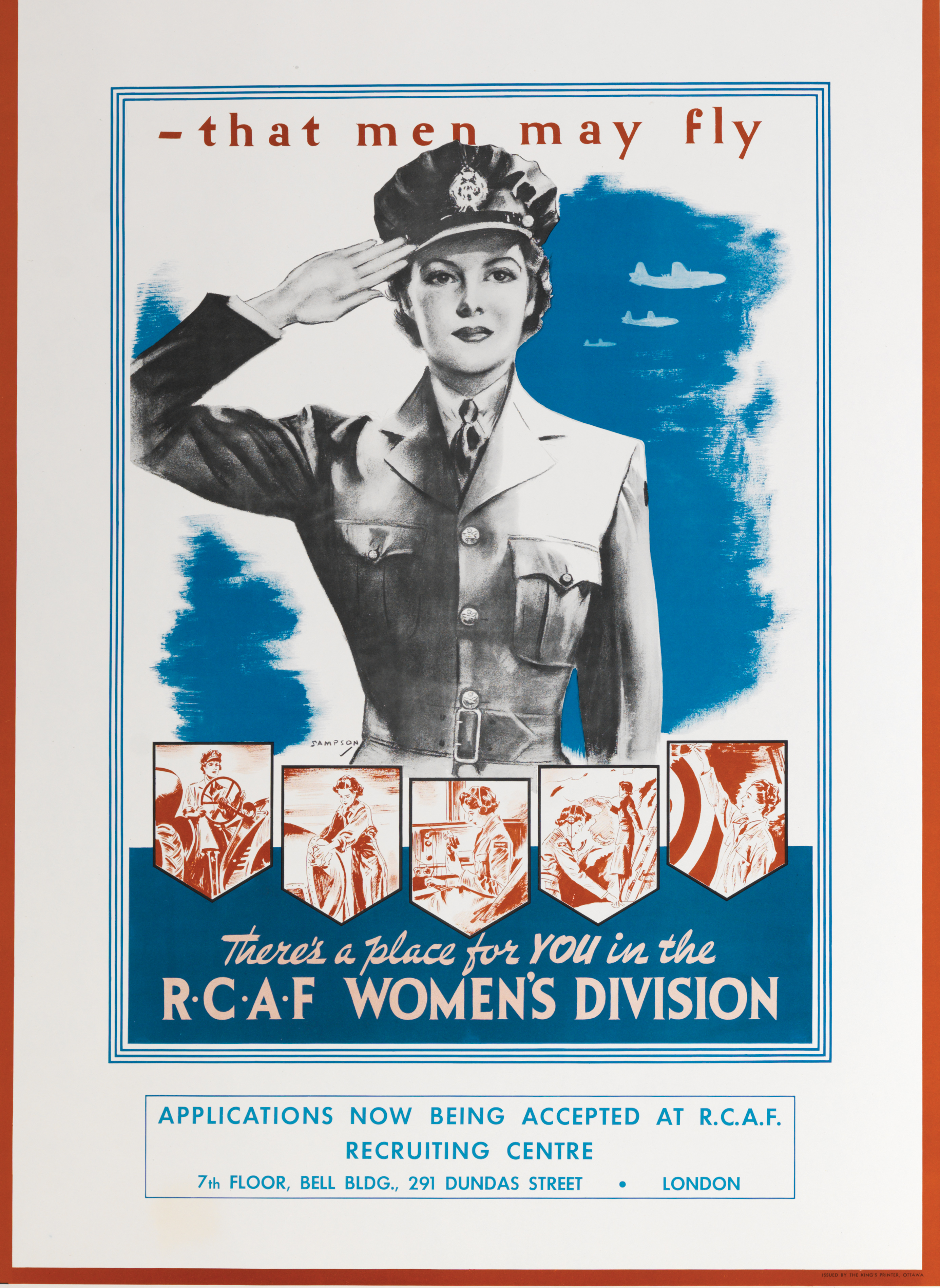

Posters recruited women to the RCAF WD. [CWM/20090063-008]

The Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) finally created the Canadian Women’s Auxiliary Air Force in 1941, and soon renamed it the RCAF Women’s Division (WD). There was a growing staffing shortage and the British Air Ministry decided to employ WAAF members at RAF schools in Canada. Again, these women were envisioned as clerical workers, but this time they would be enrolled. Military members, they argued, could be easily posted where needed and would demonstrate higher standards as per the “military point of view.”

The RCAF WD launched its “We Serve That Men May Fly” recruiting campaign, aimed squarely at white, middle-class women (and for the most part, anglophones). Women joined up, like men, out of patriotism, a sense of family tradition, a desire to travel, or to make their way in the world. In all, 17,038 women joined—eight per cent of the RCAF strength. Initially they were streamed into nine traditional “female trades”: administrative, clerks, general and stenographic, cooks, transport drivers, equipment assistants, fabric workers, hospital assistants, telephone operators, standard duties (i.e. “Joe jobs”). Within a year, women could work as lab assistants, parachute riggers and packers, and band musicians, and eventually 65 out of 102 trades were open to women.

They were even up in Whitehorse, along the Northwest Staging Route that brought thousands of planes from Montana to Alaska via Canadian airfields. In Edmonton, where the joint U.S.–Canadian Northwest Command was located, women were working in the control tower when, in 1943, there were 874 landings and takeoffs in a single 24-hour period. Margaret Littlewood, the first female to instruct on a Link trainer (flight simulator) in Canada, was working at No. 2 Air Observer School (AOS), saving lives by letting green pilots make their mistakes in simulation instead of in expensive aircraft over the prairies. No. 2 AOS was part of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP), that trained 130,000 aircrew from Britain, New Zealand, Australia and Canada, but no women were allowed, despite the need for qualified instructors and pilots. The nine other AOSs in Canada refused Littlewood’s application, but Wilfrid “Wop” May, the famous bush pilot turned base manager, took her on. “He was not a man to dilly-dally with problems,” said Littlewood. “He thought I was qualified and he didn’t care that I was a woman.”

[Canadian Aviation and Space Museum]

One of the fighter planes BCATP graduates could go on to fly in the European theatre was the British-designed Hawker Hurricane. It was Elsie MacGill, the first female aeronautical engineer in the world, who led the engineering and production of the single-engine fighter at Canadian Car and Foundry Limited in Fort William, Ont. (now Thunder Bay). The polio survivor began with a skeleton crew of 120, but within a year had 4,500 workers producing three aircraft a day for service overseas. MacGill also winterized the Hurricane for Canadian conditions and completed production-line design work for the 835 Curtiss Helldivers the firm built under contract to the U.S. Navy.

Less well-known pioneers in this area include Flight Lieutenant Margaret Parkin who joined the RCAF WD in 1942 after being the first woman to graduate from a Canadian university wearing an RCAF uniform. Her expertise was in armament research and airworthiness engineering and she went on to help design the Cold Lake Air Weapons Range and facilities.

Despite all these accomplishments and aptitudes, aircrew was completely closed to women. The closest most could get, at least until fuel rationing came into effect, was to become instructors at flying clubs giving elementary flying training to men. Then, once the WD opened up new trades, women like Molly Beall, who had an illustrious postwar aviation career, could get a bit of flight time by signing up for photography duties. This work sometimes included going up on simulated bombing exercises to document the results, and, unfortunately, several died on these missions and training runs. In the end, 28 members of the RCAF WD perished serving their country, and at least 35 were decorated for their services.

Many women were willing to assume the risks of wartime service, but the RCAF WD, despite whispers of a special women’s pilot group in the winter of 1943-44, continued to block aircrew roles. This was particularly frustrating to dedicated pilots such as Helen Harrison. “When I applied to the RCAF, I was rejected because I wore a skirt,” she said. “I was furious. I just couldn’t believe it. I had 2,600 hours, an instructor’s rating, multi-engine and instrument endorsements, a seaplane rating, and the experience of flying civil and military aircraft in three countries. Instead they took men with 150 hours.”

Harrison learned of opportunities outside of Canada to fly for the Allied war effort. She and a handful of other Canadian women travelled to Britain to be part of the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA), a uniformed civilian group that ferried operational aircraft between bases and factories during the war. The ATA was nicknamed “Anything to Anywhere,” and pilots ferried every type of aircraft the “flyboys” flew, from Tiger Moths to Spitfires to huge Halifax bombers—with no radios or armaments to defend themselves should they come face-to-face with the Luftwaffe. In the end, its 1,318 pilots ferried 309,011 planes over 414,984 hours, but always over the British Isles and Europe. The only instance of a Canadian woman performing a cross-Atlantic ferry flight was when Harrison co-piloted a North American B-25 Mitchell bomber from Montreal to Scotland in 1943.

Communications: A member of the RCAF WD operates a radio. [Ronny Jacques/LAC/e-010980583]

There was also at least one Canadian woman who took advantage of her dual citizenship to fly for the Women’s Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) in the U.S. Virginia Lee Warren of Winnipeg, along with the other 1,073 American WASP ferried planes, towed targets for gunnery practice and flew simulated strafing missions, smoke-laying exercises and experimental flights.

There was so little publicity about these organizations in Canada that most women did not know they were options. The next best thing was to find their way overseas. For some, this meant being stationed at the old U.S. Air Force base at Gander to work in radio communication, Morse code and semaphore. Newfoundland, did not become a Canadian province until 1949.

Others, like Nellie Ross, began in the RCAF WD by installing radar and sonar equipment in aircraft at Eastern Air Command in Halifax, then ended up as a signals officer at British RCAF bases. In all, about 1,500 RCAF WDs served abroad, mostly at RCAF Headquarters in London or the No. 6 Group Headquarters in Yorkshire.

The King’s approval George VI inspects RCAF WD members, Yorkshire, England, 1944. [DND/Legion Magazine Archives]

After Ross was demobilized—along with most other RCAF WDs—she found herself at loose ends, and a little depressed. She worked part-time with air force reserves from 1946 to 1951, which, she said, “was interesting work and kept me in the spin of things, as well as making the letdown easier.” She re-entered the forces in 1951 when the RCAF was again authorized to seek out female enrolment, and went to Trenton as a housing officer. She was then posted to England in 1953 for a two-year tour of duty with NATO.

Ross was part of a temporary expansion of women in the air force in the early 1950s around postwar NATO work and the Korean War. Still, only single women were allowed to enlist and they were limited to a three-year initial term (versus five years for men); at least they now received the same basic pay as men. Nearly 2,600 women enlisted in the RCAF WD alongside Ross in 1951, and by July 1953 when she was in England, it hit a high of 3,133.

By 1954, the number of RCAF WDs had plummeted to 1,000. Air force leadership kept lowering caps for female personnel, citing shorter average lengths of service and lower commitment levels. This may have been factually true—women did have a higher attrition rate—but they were caught in a no-win situation. Canadians were socialized with double standards around sexual mores, and told that women’s top priorities should be marriage and children.

If, in 1941, the RCAF had been ahead of the curve socially, gently nudging Canada to accept women in uniform, by 1964 it was woefully behind. In that year, the RCAF WD had only 566 officers and airwomen serving, and the chief of Air Staff decided to phase out female personnel completely. Luckily, the minister of national defence stepped in and asked the Department of Labour to investigate. That study showed women’s participation in the labour market was occurring at a faster rate than men’s. If the armed forces banned women it would be completely out of step with general trends. The RCAF WD continued to allow single women to serve and put a positive spin on them: their apparent attrition rates and interchangeability allowed for “force flexibility.”

The air force leadership was still not enthusiastic about women, and in 1965 their numbers were frozen at 1,500, or 1.8 per cent of the total force. They were also restricted to support roles and not allowed to serve at isolated posts like the Cold War-era Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line sites. The future of women in the Canadian Forces (as it was called under unification in 1968) was uncertain until 1971, when the Royal Commission on the Status of Women released its report. The commission, which included aeronautical engineer Elsie MacGill, issued six recommendations aimed squarely at the Forces: standardize enlistment criteria and pension benefits; allow married women to enlist; open the three military colleges to women as well as all trades and classifications. It also said that pregnancy should not automatically lead to discharge from the service. Happily, by this time, reproductive technologies like the pill had been legalized, so fewer airwomen and officers became “Pregnant Without Permission.”

Ready for action Capt. Jane Foster (left) and Capt. Dee Brasseur stand atop a CF-18 Hornet fighter jet, June 1989. [DND Archives/CKC89-3773]

The doors, however, were not quite thrown open. Women could still not be used in combat roles, on sea duty (such as sea-going helicopters), or in remote locations.

Still, there was a good-sized wedge in the door that Wendy Clay of Fort St. John, B.C., helped pry open when she became the first woman to earn her military wings in 1974. Clay had already collected a string of firsts since earning her medical degree in 1967 through the Medical Officer Training Plan. In 1969, she fell in love with flying during her flight surgeon’s course and worked steadily to achieve her private, commercial and then wings standard at CFB Moose Jaw. The aviation medicine specialist was never operational, but was completely proficient on jets.

Then, in 1978, the Canadian Human Rights Act became law and the Forces leadership foresaw a coming shortage of qualified male recruits. The next January, it announced SWINTER and would-be military pilots such as Dee Brasseur and her cohort presented themselves for the trial program. There were only 207 applicants during the program’s six years, far fewer than hoped for, and as Shirley Render notes in her book, No Place for a Lady, some of the women cited lack of publicity and misinformed recruiters. “One woman said she applied four different times before she was allowed to sign up for pilot training,” Render writes.

SWINTER was meant to research how women fared in near-combat roles, which was ironic, since female nurses had been on the battle lines for over a century and women were serving with NATO in Europe and with the United Nations Emergency Force in the Middle East. But Maj. Brasseur and her cohort were willing to put up with the misperceptions and challenges because, as she said, “Flying presented the ultimate physical and mental challenge, definitely the job for me.” Her persistence paid off: in 1988 she and Jane Foster became the world’s first female fighter pilots and Brasseur flew CF-18s the next year with the NATO-dedicated Tactical Fighter Squadron. “My job was to intercept invading nuclear bombers and engage their fighter escorts in individual dogfights or to rush to Europe, bombing and strafing Warsaw Pact ground forces.”

During the 1980s, Brasseur was also invited to join the Charter Task Force that studied the feasibility of women as fighter pilots, and was one of the first female jet pilot instructors. At first, she recalled, there was quite a bit of resistance to her. Then, she noted, “as the program progressed some of the younger guys assumed that there had always been women and it was not such a problem.”

Throughout the 1980s and ’90s, women aviators were sent to hot spots around the world: the Sinai Desert, Libya, Kuwait and Bahrain, to name a few. They were also sent to very cold spots, flying and navigating C-130 Hercules aircraft as part of Operation Boxtop to Alert station in the High Arctic.

The air force finally removed all restrictions in 1989 as the Berlin Wall crumbled. It had taken many years, many determined women, and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, to finally remove official gender discrimination in the air force. Still, women continued coming up against a “Plexiglas ceiling” in their careers. Female military members reported harassment at a much higher level than men, and noted the Canadian Forces failed to co-locate married couples. Because of historic policies that blocked women’s opportunities for informal learning and skill development (not having access to mixed-gender ships in naval aviation, for example), this meant a wife’s career generally took a back seat to her husband’s.

Another big hurdle for women in the air force were regulations that put them on medical leave and grounded them instantly if they became pregnant. This, of course, affected their benefits, job security and seniority unfairly. In the 1980s, two Canadian Forces pilots (and two airline pilots) became pregnant at the same time and were able to challenge these regulations successfully. This change recognized that pregnancy and parenthood were normal parts of a military (or civilian) career, and that both men and women should have access to parental leave. By the 1990s, Capt. Micky Colton noted, “there were no restrictions. You officially stop flying when you and your medical officer feel the time is right.”

Shifts in a country’s or organization’s culture take time and strong leadership, and it has been the same for the air force. In order to make an equitable work environment and attract more female members, the RCAF has changed harassment policies, brought in mandatory training programs and even tweaked uniforms, equipment and gear to make them more suited to women. It also signed on to UN Security Council Resolution 1325—Landmark Resolution on Women, Peace and Security, and developed a national action plan around it in 2010. In 2015, the Canadian military launched Operation Honour to eliminate harmful and inappropriate sexual behaviour.

The goal of the Canadian Forces’ military aviation units and female pioneers has been the same: to increase the numbers of women in the Forces until they are no longer seen as special. When Brigadier-General Lise Bourgon, who became the first female wing commander of 12 Wing in Shearwater, N.S., noted that “female aircrew and maintainers were a common sight” there, it was a victory for all.

Lieutenant-General Michael Hood, the commander of the RCAF, recently said his “most important job is building the air force of 2030.” That air force, if it wants to serve Canada and reflect its diversity, has a way to go. Right now women make up 18 per cent of the total, and only three per cent of pilots. Looking upstream, there is cause for hope: air cadet squadrons like 699 in Edmonton are almost at parity (and include many people of colour, another area of development), and the Royal Military College has issued a directive that in 2017 a minimum of 25 per cent of first-year cadets should be women. Hopefully, young girls will see retired lieutenant-colonel Maryse Carmichael, honourary president of the Air Cadet League of Canada—the first female Snowbird pilot and team leader—and see themselves at the controls. Hopefully, as they hear about women involved in aerial campaigns over Afghanistan and, more recently, Bourgon’s command of Joint Task Force Iraq against ISIS, they will see themselves in leadership roles.

Advertisement