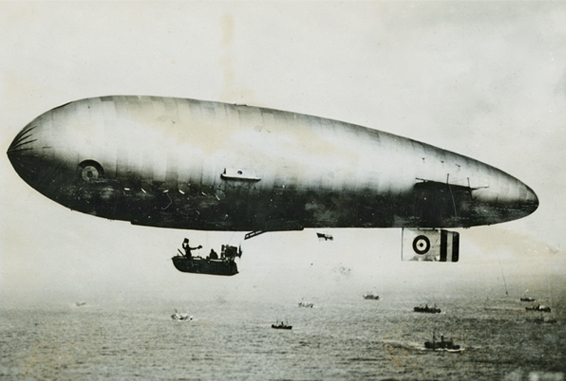

A signaler in the gondola of British Airship No. 37 uses flags to send a message to a convoy. By November 1918, the Royal Air Force had more than 100 airships. [CWM/19940003-735]

Early in the First World War, flying boats,

seaplanes and airships were thrust

into battle over the ocean

The airplane was barely 11 years old when it went to war. By the age of 15, it had matured into a formidable weapon. When not delivering death and chaos to the enemy, it was helping other arms, notably artillery, to be more effective. With the exception of moving troops and heavy cargo, aircraft in 1914-18 carried out the same functions they would in the Second World War, including deployment against submarines.

That role had been forecast before the war, but the airplanes first needed considerable improvement. Flying over the sea was inherently hazardous, so engine reliability needed attention if the planes were not to be nursemaided by the ships they were supporting. Next came the matter of improving range, then adding a reliable and effective ordnance load. Not surprisingly, the greater burden of anti-submarine operations fell to float-equipped sea-planes and flying boats. Nevertheless, the technology had to evolve, including strengthening floats and hulls. All major powers tried to develop effective anti-submarine aircraft, none so extensively as Great Britain. The Royal Naval Air Service (merged into the new Royal Air Force on April 1, 1918) was in the forefront of both research and operations, and Canadians were in the thick of it.

Only one submarine was unequivocally

destroyed at sea by an airplane—unaided—

during the First World War.

By 1917, the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) had effective patrol aircraft—the Curtiss H-12 and H-16 Large American flying boats, which soon evolved into the Felixstowe F.2 and F.3. These came with two powerful Rolls-Royce Eagle engines with up to 350 horsepower, a bomb load capacity of 210 kilograms and endurance of six hours flying time. Unhappily, the top speed of 153 kilometres per hour was insufficient to ensure surprise when attacking a U-boat.

Patrols produced unexpected results, including a decrease in mine-laying sorties by enemy destroyers sailing from Belgian ports. However, submarines were the main prey. In 1917, Royal Flying Corps and RNAS aircrews sighted 168 U-boats around the British Isles and attacked 105 of them. The busiest station was Felixstowe, Norfolk (with 44 sightings and 25 attacks, all by flying boats), followed by Mullion, Cornwall (with 17 sightings and 12 attacks, all by airships). The aircrews claimed several sinkings, but postwar analysis produced conflicting conclusions as to what had caused the demise of some German submarines—mines, ships, aircraft, or combinations of them.

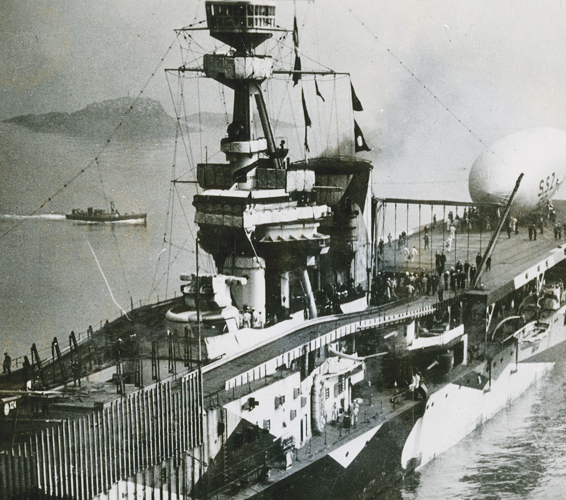

The British battlecruiser HMS Furious was fitted with flight decks fore and aft. A Sea Scout Zero non-rigid airship, or blimp, is on the stern deck. [CWM/19940003-724]

For the record, only one submarine was unequivocally destroyed at sea by an airplane—unaided—during the First World War. That was the French submarine Foucault, bombed and sunk in the Adriatic Sea by Lohner flying boats of the Imperial Austro-Hungarian Naval Air Arm on Sept. 15, 1916. However, there is a strong case to argue that Flight Lieutenant Norman Ashley Magor of Montreal destroyed a U-boat on Sept. 22, 1917. His victim was most likely UB-32, which the Germans recorded as having been lost without explanation about this time.

Magor’s career was particularly adventurous. On Sept. 15, 1917, his H-12 was attacked over the North Sea by two enemy seaplanes; one was shot down in flames. On Sept. 22, he dropped two 104-kilogram bombs from an altitude of 240 metres; they exploded just behind the conning tower. The vessel submerged, leaving a quantity of wreckage on the water. A week later, Magor attacked another submarine, but his bombs fell wide of the target. He was awarded a Distinguished Service Cross, and was killed in action off the French coast on April 25, 1918, shot down in another H-12 by enemy seaplanes.

Hobbs dropped another bomb,

which exploded five metres off the bow.

His target was sinking as he left for base.

Another case of destruction by airplane may be made for the demise of UC-6, a German minelayer out of Zeebrugge, Belgium. It may have become entangled in nets, but in any case it was surfaced and stationary on Sept. 28, 1917, when an H-12 piloted by Flight Lieutenant Basil D. Hobbs of Sault Ste. Marie, Ont., bombed it from 180 metres in the North Sea, scoring a direct hit on the stern with a 104-kilogram bomb. The flying-boat crew observed a large tear in the hull. Hobbs dropped another bomb, which exploded five metres off the bow. His target was sinking as he left for base.

Flying a Curtiss H-12 with the Royal Naval Air Service, Basil D. Hobbs was instrumental in destroying a German minelayer in the North Sea in 1917. [LAC/MIKAN-4818430]

Flight Lieutenant Joseph O. Galpin of Ottawa had an experience that was more typical of flying-boat patrols. Flying an H-12 out of Felixstowe on Nov. 3, 1917, Galpin sighted a fully surfaced German submarine halfway across the English Channel. Within three minutes, the target had submerged. Galpin’s two bombs exploded nine metres to the left and six metres ahead of the swirl, but no evidence of damage appeared.

Flight Sub-Lieutenant Robert T. Eyre of Toronto had a similar experience. On Dec. 21, 1917, flying a Wight Seaplane from Cherbourg, France, he sighted a U-boat five kilometres away. It dove when he was less than a kilometre away, leaving no trace in the prevailing swell. Eyre dropped one bomb in its approximate position without apparent result. Nevertheless, he had probably frustrated its attack on a nearby French convoy.

Even if Allied “killed” and “damaged” results were poor, the value of air patrols was unquestioned, especially once the convoying of merchant shipping began in 1917. Submarines dove at the first sight of a patrol plane, their captains uncertain if they had been sighted or if a warship had been summoned to deal with them. It is difficult to measure effectiveness in terms of ships not sunk. R.D. Layman, in his book Naval Aviation in the First World War: Its Impact and Influence, notes that of 257 merchant ships sunk in convoy in the last 18 months of the war, only two were lost when the convoys were under aerial protection.

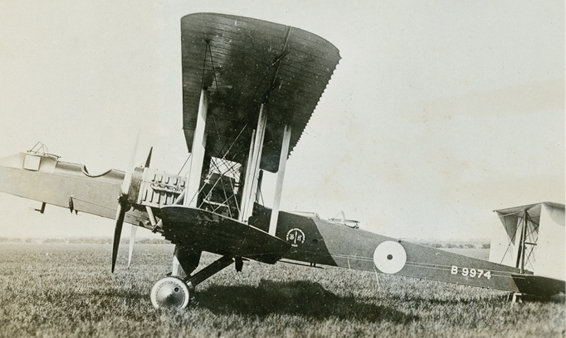

Other than the flying boats, various aircraft flew anti-submarine patrols. In 1918, several squadrons along Britain’s east and south coasts operated de Havilland DH.6s. These were obsolete training aircraft, so underpowered that it was necessary to choose between carrying an observer or a token bomb load. They were useful enough as “scarecrows.”

The ungainly Blackburn Kangaroo was used in limited numbers, but had the most outstanding anti-submarine record of all First World War aircraft. This was partly due to the conditions where it was used—hunts where submarines were known to be. Nevertheless, it offered excellent forward visibility and a rapid turning rate. In only 600 hours of flying, Kangaroos spotted 12 submarines, attacked 11, damaged four and were instrumental in the destruction of one, which was crippled from the air and finished off by a patrol vessel.

Lieutenant Robert R. Richardson of Guelph, Ont., had been wounded with the Canadian Expeditionary Force in 1916 before transferring to the RNAS. He was finally posted to Seaton Carew in northeast England, flying Kangaroos in No. 246 Squadron. Richardson made no fewer than five attacks on submarines—on June 8 and 13, July 26 and 28, and Sept. 3, 1918. On July 28, his bombs failed to explode, while on Sept. 3, there was no surface vessel on hand to

exploit his attack.

The underpowered de Havilland DH.6 was useful as a “scarecrow” to warn away U-boats. Some 44 Canadian pilots and two Canadian observers served with Britain’s DH.6 units. [CWM/19940003-760]

Land-based planes on the Continent also played a part. Flying DH.4 aircraft from Bergues in northern France, No. 217 Squadron was primarily engaged with bombing targets in Belgium. However, it occasionally looked seaward. Two Canadian pilots made promising but unsuccessful attacks on submarines in the Channel: Captain Harold H. Gonyou of Toronto on April 3, 1918, and Captain Kenneth H. Boyd of Chatham, Ont., on Aug. 12, 1918.

While airplanes were the most prominent tools in aerial anti-submarine warfare, airships were also deployed. Best known are the German Zeppelins, rigid airships that achieved limited success in fleet reconnaissance and notoriety in bombing British cities. The Allies had nothing comparable to the “Zeps.”

Nevertheless, the RNAS operated a large fleet of lighter-than-air machines. It had six as of August 1914; by November 1918, the RAF had 111 of various designs, including six rigid airships. The RNAS and RAF scrapped, lost or rebuilt dozens of airships through the war; 48 men were killed in accidents or enemy action; and 28 craft were transferred to Allies such as Italy. Several were gifted to Canada after the war but were never uncrated.

Repeated attempts to use these “battle bags” in fleet reconnaissance were unsuccessful; airships were too ungainly and vulnerable to changing weather to be reliable scouts. They found wider use in an anti-submarine role, principally as scarecrows. No slow-moving airship could hope to surprise and attack a U-boat before it submerged. However, experiments conducted in 1918 used hovering airships with hydrophones aimed to detect submerged submarines—a tactic now used with helicopters.

John A. Barron of Stratford, Ont., is the Canadian most closely associated with First World War lighter-than-air operations. He joined the RCN before the war, but was invalided out on medical grounds. He was fit enough, however, to be accepted by the Royal Navy in August 1914. He was soon a flight lieutenant in the RNAS, posted to Kingsnorth and then to operational units.

On Sept. 9, 1916, commanding His Majesty’s Airship C-10 from the Coastal Class of non-rigid airships, he embarked on a memorable 7.5-hour patrol off The Lizard peninsula in Cornwall. This was a second-generation airship, with engines at either end of a box-like gondola. The sight of two burning vessels led him to a surfaced U-boat, which submerged well before he dropped his bombs. He radioed a warship, which rescued the ships’ survivors and searched briefly for the enemy vessel. His flight had more drama when a fuel pipe leading to the forward engine broke; his mechanic took a spare pipe, climbed out on the skid and made inflight repairs.

Submarines dove at the first sight

of a patrol plane, their captains uncertain

if they had been sighted.

Barron later served in the Mediterranean and was decorated by the Italian government for helping establish an airship squadron at Taranto. Posted to the United States in 1918, he was then attached to the RCN as the Royal Canadian Naval Air Service, (RCNAS) was being formed. The Armistice ended that. From 1920 to 1922, he was seconded to the Canadian Air Board, but when the gifted British airships remained packed away, he returned to RAF service until 1925. Barron eventually came back to Canada, and during the Second World War, he served as a civilian ground school instructor at No. 10 Elementary Flying Training School in Mount Hope, Ont. He died in Toronto in 1956.

The twin-engine Blackburn Kangaroo, introduced in 1918, was the war’s most effective anti-submarine aircraft. Lieutenant Robert R. Richardson of Guelph, Ont., flew the Kangaroo in five U-boat attacks. [DND/LAC/PA-006361]

The RCNAS evolved because the aerial anti-submarine campaign had been extended to the western Atlantic Ocean by 1918. That summer, five German U-boats were seen operating off the East Coast. The danger had been foreseen. As early as Feb. 10, 1917, the Honourable J.D. Hazen, Minister of the Naval Service, had raised the issue of a possible naval air service for “the adequate defence of the Atlantic coast.” The Cabinet turned it down in March because of costs.

American entry into the war on April 6, 1917, and the insertion of U-boats into the western Atlantic gradually changed official attitudes. British officers—Barron included—were dispatched to Canada as advisors, and the U.S. Navy made clear its willingness to co-operate against the submarines. It was prepared to furnish aircraft, airships and balloons until Canadian defences could be assembled. The general outlines of such defences had been laid down by April 1918; the first air station sites had been selected at Dartmouth and Sydney in Nova Scotia. Bases in Newfoundland would have been added if the war had gone into 1919. Wing Commander J.T. Cull, a Royal Air Force officer, was sent to Canada to get the ball rolling. The Royal Canadian Naval Air Service was established by Order-in-Council on Aug. 5, 1918.

It was an air force without aircraft or trained personnel. More than 600 young men applied to join, but until they could be instructed in technical and flying duties, the aerial defence of the East Coast would be assumed by the U.S. Navy. An advance party arrived in Halifax on Aug. 5, along with four Curtiss HS-2L flying boats. Personnel were billeted in tents until barracks and hangars were built. Lieutenant (later Admiral) Richard E. Byrd commanded both bases. The United States made it clear it was there as an ally, but was not under British or Canadian command; the Stars and Stripes flew over the air stations.

The Americans arrived without anti-submarine bombs, which had gone astray during transport. Byrd borrowed some naval depth charges, although their delicate priming mechanisms made them dangerous. Operational flights from Dartmouth began at the end of August, and from Sydney on Sept. 29. Both stations eventually had six HS-2Ls on strength. Apart from patrols flown out to sea (100 kilometres with outbound convoys, 130 kilometres with inbound ones), they searched the indented coastline for possible submarine anchorages, flew exercises with surface vessels, and dropped leaflets promoting Victory Loan campaigns.

Meanwhile, the RCNAS was taking shape, though things were complicated by the 1918 Spanish flu epidemic. A distinctive uniform and aircrew badges were designed at the outset; 64 cadets selected in September were sent to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for the ground school instruction that would precede flight training. A dozen more cadets and six RCN ratings were posted to Britain to commence airship training.

However, the RCNAS never got airborne. The Armistice on Nov. 11 rendered it redundant and it was disbanded on Dec. 5. At Halifax and Sydney, the Americans began packing early in December, and their bases were paid off on Jan. 7, 1919. As a gift to Canada, they left behind 12 HS-2Ls, 26 Liberty engines and four kite balloons. A year later, the Dartmouth base was back in operation, performing both civil and military duties under the Canadian Air Board.

Advertisement