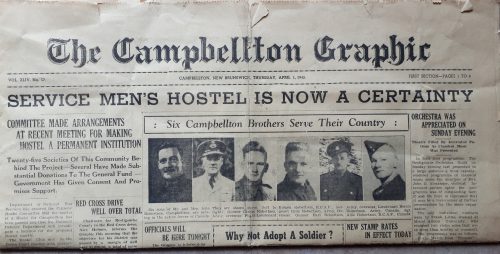

CLICK TO ENLARGE – Campbellton, N.B., was justifiably proud of the six Robertson brothers. [Debbie Magusin/Robertson family archive]

“The whole city was so proud of these six boys.”

There were six of them, Robertsons all, who joined the Canadian forces, left their hometown of Campbellton, N.B., and sailed overseas to serve in the Second World War.

Every one of the brothers survived the fighting, yet each died before his time, victims of more insidious killers than Axis bullets and bombs—namely, cancer and cardiopulmonary disease. None saw the age of 80.

Born in 1910, Gerald was the oldest. He joined the army and served as a gunner during the Italian Campaign. Born 12 years after his oldest brother, Earl was still a teenager when he followed in his footsteps, joined the army and served as a gunner in Italy and the Netherlands.

The others filled a variety of roles, although none joined the navy despite Campbellton’s proximity to the ocean.

Rolland (Rollie) signed on with the Royal Canadian Air Force and flew Wellington, Halifax and Lancaster bombers; Allan (Allie) became an air force sergeant and served as a wireless operator in England; Osborne (Bernie) was a highly decorated army major wounded after landing on D-Day; and Colin (Collie) served as a signalman aboard a tank, trekking across Europe through 1944-45.

Located on the south bank of the Restigouche River in northern New Brunswick, the lumber town of Campbellton hasn’t grown much since the census of 1941, which recorded 6,748 residents (there were just 6,883 in 2016).

It’s a close-knit community, and when the six sons of John and Alma Robertson found themselves in uniform, it was front-page news in the Campbellton Graphic.

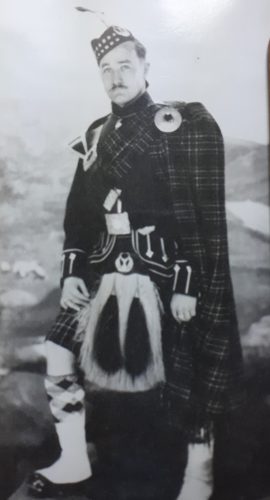

Bernie Robertson in full Scottish kit. [Debbie Magusin/Robertson family archive]

Family, friends and neighbours would turn up at the Campbellton train station to bid farewell as each left town.

Gerald Robertson was the oldest of the brothers. He served as an army gunner during the Italian Campaign. [Debbie Magusin/Robertson family archive]

“They really were splendid men. They were very clever in school, always at the top of their class.”

Bernie took a shrapnel wound to the knee in Normandy.

At least two of them, Bernie and Rollie, would take on the roles of instructor before heading overseas.

“They were athletic and salt-of-the-earth sort of people. The whole town rallied behind them. I’d often have people come up to me and say “oh, it must be so nice to have uncles like that.’ They were very well-known.”

Earl Robertson was a teenager when he joined the army and served as a gunner in Italy and the Netherlands. He went on to travel the world after the war, settling for a time in New Zealand. [Debbie Magusin/Robertson family archive]

The family was of Scottish roots—there’s a photograph of Bernie in all his regalia—and the boys were very much the products of their traditional upbringing: modest, resolute and matter-of-fact about their wartime service. They rarely, if ever, spoke of it.

But Remembrance Days, says Magusin, were a “huge thing” in the Robertson family during the 1950s and ’60s. Rollie never missed one, said son Ken. Magusin remembers attending a Nov. 11 ceremony with her Uncle Allie long ago.

Rollie Robertson (centre) settled in Calgary after the war. [Debbie Magusin/Robertson family archive]

“I remember being so shocked because they were stoic Scotsmen—they didn’t cry. The realization hit at that time what these men must have gone through. I think I was only about eight or nine years old.”

Rollie Robertson escorts a dignitary during a troop inspection. [Debbie Magusin/Robertson family archive]

Bernie was still a lieutenant when he earned a Military Cross leading a “lost platoon” back to friendly territory in France. A period newspaper report said he “met advancing German troops alone and showered them with hand grenades while his men evacuated the wounded and reached safety.”

Living in Yarmouth, N.S., at the time, his wife Ruby (her father was a First World War veteran) received a telegram informing her that her husband and his men were missing in action and had been “given up for lost.” Word that they were safe arrived the next day.

His medal, awarded for “exemplary gallantry during active operations against the enemy,” was pinned on his chest by King George VI at Buckingham Palace.

Bernie took a shrapnel wound to the knee in Normandy. He went on to join the Carleton and York Regiment and fought in the liberation of the Netherlands. He had a limp the rest of his life.

Collie kept a graduation picture of his fiancée in his breast pocket, noting on the back the towns in France, Belgium, the Netherlands and Germany he travelled through with the Canadian Fourth Armoured Division in 1944 and ’45. He was his crew’s lone survivor after their tank was hit, the charred edges of the picture a testament to that day on which his attempts to save his crewmates earned him a Mention in Dispatches.

“I am beyond proud of my father Colin Robertson and his five brothers,” said his daughter Bonnie. “They were all young men who were compelled to serve out of the deepest ingrained sense of fighting for the right.”

Her father had initially tried to enlist in the air force but had been refused due to colour blindness. He enlisted in the army at 21.

“He never spoke of the ordeals, only the odd funny anecdote. He always wanted to protect his girls from the brutal reality of this war. After much research I have learned of the horrors that they faced, unimaginable images that re-appeared in nightmares for the rest of their lives.

“Such were the men who went to war, and we owe them everything.”

Rollie, said Ken Robertson, rarely spoke of the war, either.

Rollie Robertson and his wife Dorothy. Rollie flew bombers during the war, including the Lancaster. [Debbie Magusin/Robertson family archive]

The second-oldest of the Robertson boys, Rollie enlisted on July 16, 1941. After earning his wings, he trained pilots at Hagersville, Ont., before shipping out for England in 1943, a flight-lieutenant.

“I do remember him saying the saddest times overseas were walking though the barracks and seeing beds that had not been slept in—a sign that a crew had not returned.”

Ken still has the small prayer book titled Be Thou My Battle-Shield, Sword for the Fight, which his father kept with him in his flight jacket. The booklet was issued by The War Service Committee of The United Church of Canada.

Collie Robertson (left) was a signalman aboard a tank in WW II Europe. Bernie was a highly decorated army major who landed on D-Day and was wounded in Normandy. [Debbie Magusin/Robertson family archive]

Magusin remembers as a little girl looking forward to her uncles’ visits. “They were all such joyful people,” she says, suggesting they weren’t about to let the war hold sway over the rest of their lives. They boxed, swam, lifted weights. Family photo albums are bursting with pictures.

Several of the brothers took advantage of government postwar programs for veterans, went to university and got degrees.

Earl was an adventurer in his time. He swam the English Channel and travelled the world for 15 years, settling in New Zealand for a while before returning to Campbellton. Collie moved to Nepean, Ont., where he became an engineer and national weightlifting coach. Two of his daughters retraced his route through Europe in 2018, driving the same roads he travelled and fought over.

Rollie was a mediator with Texaco in Calgary.

His medal was pinned on his chest by King George VI at Buckingham Palace.

Allie settled outside Montreal; Bernie near Chatham, N.B. The family lost track of Gerald, who went his own way after the war. He died in 1967, at 56 years old.

Earl was the last to go, and the longest lived. He passed away in 2001, at age 79.

Among them, the six war veterans left a legacy of 20 children, 22 grandchildren and 20 great-grandchildren.

“My uncles touched a very deep part of me. The part that believes in decency, compassion and loyalty,” said Magusin. “Their memories have given me the strength to accept life’s blows without complaint. They truly were remarkable men, honourable men and lovely men. My heart is full.”

Advertisement