A wartime image of Colditz Castle.[ignsofwar.com; Johannes Lange/global.museum-digital.org/1493745]

Colditz is perhaps the best known of all the Second World War German prisoner-of-war camps. Several books, a movie and a television series have all immortalized Offizierslager (Oflag) IV-C Colditz as a facility where British officer PoWs taunted (“goon-baiting” as they called it) their guards and planned elaborate escapes involving tunnels, detailed disguises and even a glider.

Many turned their plans into reality. Those who didn’t make a “home run” back to Britain but got recaptured, however, returned to face a stint in solitary confinement before reuniting with their fellow prisoners. The jail was a miserable, cramped and damp castle where a near-starvation diet along with gloomy weather drove some of the incarcerated to madness—and others to suicide.

Belgian and French prisoners gather in a Colditz courtyard.[museum-digital.org/1493691]

Schloss Colditz is in the German town of the same name near Leipzig and Chemnitz in the state of Saxony. It’s on a hill spur overlooking the river Zwickauer Mulde, a tributary of the Elbe River.

First built in 1158, the castle was destroyed and rebuilt twice, taking on its current Renaissance-era appearance between 1577 and 1591. In its early days, the Schloss was used as a hunting lodge. In 1694, it was expanded with a second courtyard and a total of 700 rooms.

From 1803-1829 it was a workhouse for the poor, and then it was converted into a sanatorium for wealthy patients. It served in this capacity for more than a century until the Nazis gained power in 1933. They converted the castle into a political prison.

British prisoners of war at Colditz in April 1945. A pamphlet detailing how Canadians could help PoWs.[Wikimedia; W.E. Storey Collection; global.museum-digital.org/1347703]

A prison portrait believed to be of Lieutenant C.D. Mackenzie and Canadian Pilot Officer Howard (Hank) Wardle (immediate left).[global.museum-digital.org/1347441]

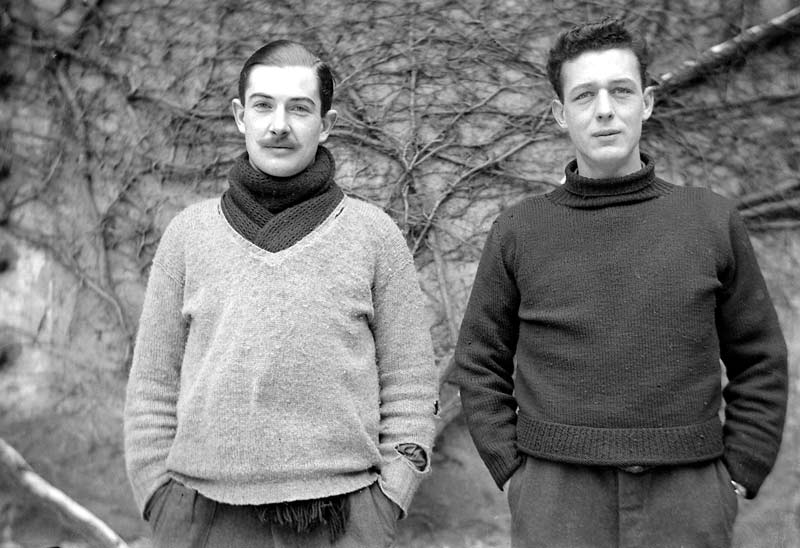

Kenneth Lockwood (far left, left), one of the first British held at Colditz, with an unidentified Polish prisoner.[Imperial War Museums/Wikimedia]

After the outbreak of the Second World War, the Schloss was transformed into a high-security prisoner-of-war camp for officers who were escape risks or regarded as particularly dangerous. The facility’s population was initially cosmopolitan, consisting of PoWs from Poland, France, Belgium and the Netherlands. Beginning in late 1940, the first British began to arrive, and during the next three years each contingent competed to see who could escape most often.

By 1943, Colditz was largely a British camp with some Americans, all other nationalities having been moved to other locations. The term British, of course, was quite broad and encompassed Commonwealth personnel from Canada, Australia and even India. Some notable prisoners included British fighter ace Douglas Bader, New Zealand Army Captain Charles Upham, the only combat soldier awarded the Victoria Cross twice, and David Stirling, founder of the wartime Special Air Service. Along with these officers were several British of other ranks who served as cooks and batsmen and weren’t included in any of the escape plans.

David Stirling, founder of the British Special Air Service, was one of Colditz’s most notable detainees. [Imperial War Museums/Wikimedia]

One of the first Canadian prisoners at Colditz was Pilot Officer Howard (Hank) Wardle, of Dauphin, Man., who had joined the Royal Air Force in March 1939.

Wardle’s Fairey Battle light bomber had been shot down near Crailsheim, Germany, on April 20, 1940, while he was conducting a reconnaissance mission with 218 Squadron. Wardle was captured and, after being interrogated at a Luftwaffe barracks, he was detained at Oflag IX-A/H in Spangenberg, Germany. In August, he escaped the camp, but was recaptured the following day and transferred to Colditz.

On Oct. 14, 1942, Wardle, along with three British officers, successfully escaped Colditz.

On Oct. 14, 1942, Wardle, along with three British officers—including Captain Patrick (Pat) Reid whose 1952 memoir, The Colditz Story was the basis for the film of the same name—successfully escaped Colditz. Wardle and Reid crossed the Swiss frontier at Singen, Germany, a known border weak spot, four days later.

French PoWs dug this tunnel—ultimately 44-metres long—under the castle’s chapel in 1942 in another foiled breakout.[Johannes Lange/global.museum-digital.org/1347568]

In late 1943, Wardle made his clandestine journey to Spain, paid for by the British, arriving in the Spanish village of Canejan just before Christmas 1943.

Wardle returned to England via Gibraltar on Feb. 5, 1944, and was awarded the Military Cross on May 16. He passed away in Ottawa in January 1995, aged 79.

Not all Canadians held at Colditz were as lucky as Wardle, however. Captain Graeme Delamere Black, was one of seven men of No. 2 Commando who were captured in September 1942 after Operation Musketoon, the destruction of the German-held power plant in Glomfjord, Norway. Originally from Dresden, Ont., prior to the war Black had served with the Queen’s York Rangers (1st American Regiment) and, after moving to London, he joined the South Lancashire Regiment (Prince of Wales’s Volunteers) before volunteering for the commandos. All seven of the PoW commandos were held in Colditz before they were executed under Hitler’s Commando Order—a directive that all captured Allied commandos be killed without trial—on Oct. 23, 1942.

As they advanced to the castle, the troops were surprised to learn that it held some 250 Allied PoWs who had been watching the whole battle from the windows.

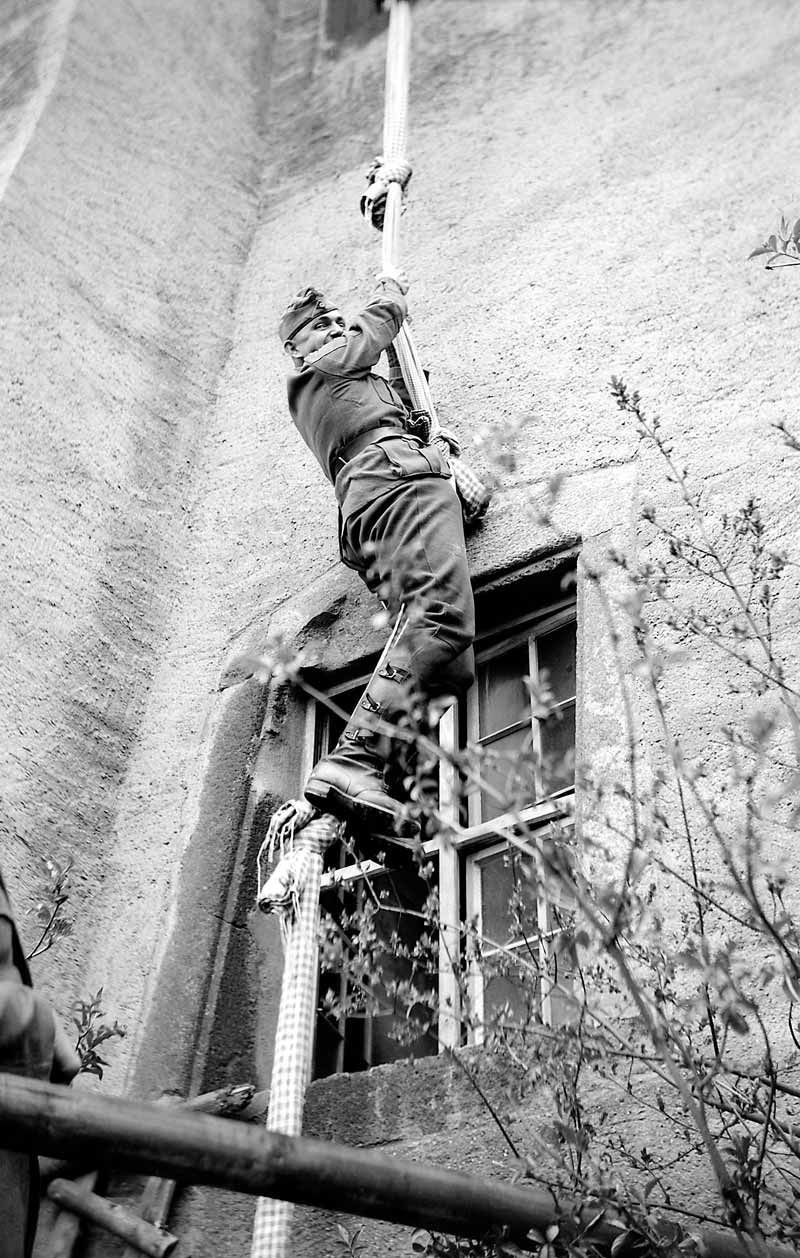

German officers pose with a rope, made of knotted bedsheets, from a failed escape attempt. [Johannes Lange/global.museum-digital.org/1347546]

Years of captivity at Colditz also took a terrible mental toll on many prisoners and Flight-Lieutenant Frederick Donald Middleton of Dauphin, Man., was no exception. One of three brothers who enlisted in the RAF in 1937, Middleton’s Hampden bomber of 50 Squadron was shot down over Norwegian waters on April 12, 1940. Taken prisoner, he arrived at Colditz with Wardle after an unsuccessful escape from the PoW camp in Spangenburg. While at Colditz he suffered severe depression and attempted suicide numerous times. Middleton was then transferred to a mental hospital for PoWs and, once deemed well, he was sent to Stalag Luft III. There he helped dig the “Harry” tunnel renowned in the 1944 “Great Escape,” but the route was discovered before Middleton got his turn to use it.

In 1945, Middleton returned home a shadow of his former self, weighing less than 100 pounds and suffering what today would likely have been diagnosed as post-traumatic stress disorder. While Middleton recovered physically and began to live a normal life to the best of his ability, he never truly regained his emotional health. Sadly, for some, there was just no escaping from Colditz.

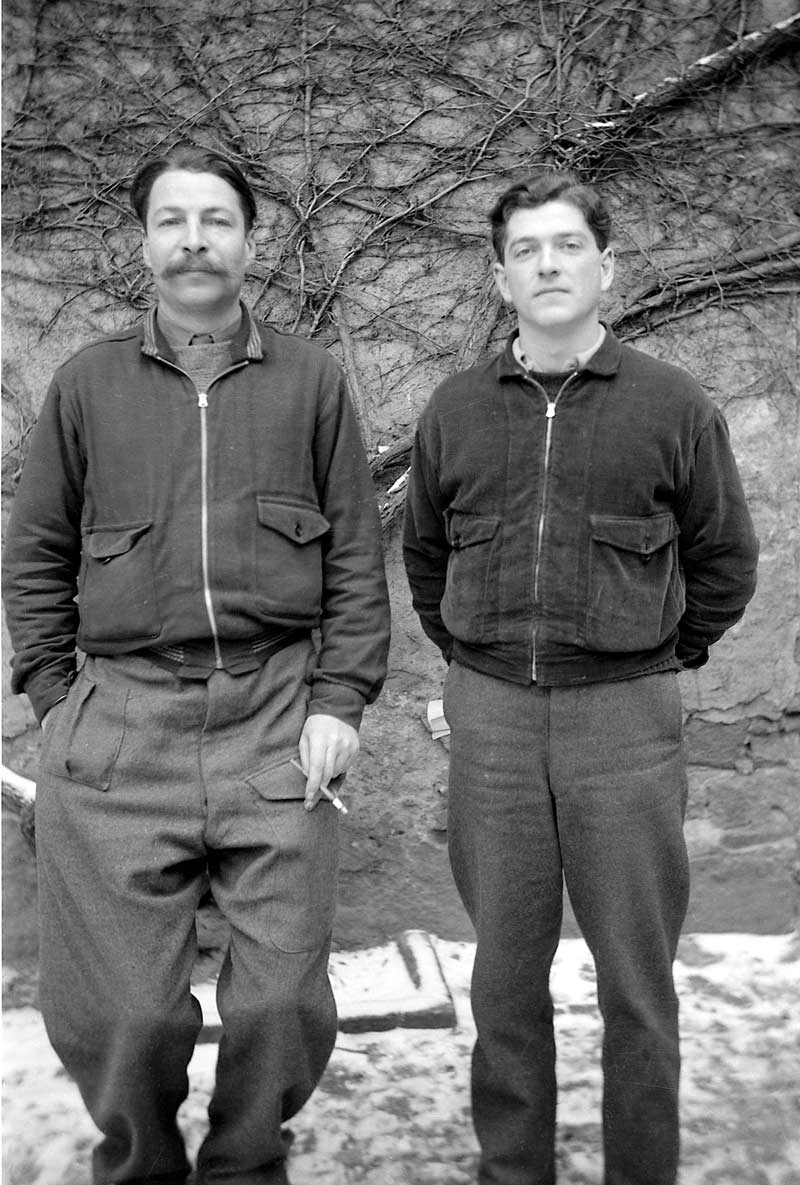

British PoWs Jim Rogers and Giles Romilly, the latter specially guarded because he was the nephew of Winston Churchill’s wife. [Johannes Lange/global.museum-digital.org/1347686]

A Colditz guard climbs a homemade rope in re-enacting an unsuccessful escape.[Johannes Lange/global.museum-digital.org/1347542]

Interned at Colditz were also several prisoners called prominente, or German for celebrities, all relatives of Allied VIPs. Two were particularly noteworthy: Giles Romilly, a journalist who was captured in Narvik, Norway, and was the nephew of Winston Churchill’s wife Clementine; and British Commando Michael Alexander, who claimed to be the nephew of Field Marshal Harold Alexander to avoid execution, though he was merely a distant cousin.

By March 1945, the number of high-profile inmates had swollen to 21. With the Reich collapsing on all sides, they were to be used as bargaining chips with the Allies. In early April, the prominente were all transported out of the castle by the SS. After a harrowing trip south, they were liberated by the advancing American 7th Army outside of Innsbruck, Austria, in late April.

The liberation of the prison itself began on April 15, as advancing elements of the 3rd Battalion, 273rd Infantry Regiment, approached from the southwest. A sharp, day-long firefight ensued as SS troops and Hitler Youth desperately tried to stem the attack. Some 20 Americans died in the street fighting.

By the next morning, however, the Germans had left, the white flags were up and, as they advanced to the castle, the troops were surprised to learn that it held some 250 Allied PoWs who had been watching the whole battle from the windows. Two days later, the freed men left the Schloss for the last time and, after spending an evening in Erfurt, they were flown back to Aylesbury, England.

The infamous Colditz Castle had finally been physically escaped for the last time.

Return to Colditz

For the average Canadian, Colditz is slightly off the beaten trail, located as it is in the former East Germany. The site has always fascinated me, and I first visited in the spring of 1994 while on leave during a year-long deployment with the United Nations Protection Force Headquarters in Zagreb, Croatia. I was travelling with a Belgian colleague, and we found a sleepy little town just emerging from four decades of Communist rule.

Colditz Castle (bottom) and the unsuccessful French escape tunnel (below) in more current times. [Ed Storey]

[Ed storey]

Reminiscent of the Balkans, the town was in decent shape, though much of it needed work other than the newly established gas station and car dealership. The castle still had its foreboding wartime look, but the small museum dedicated to escape was in a building outside the walls and most of the outer courtyard rooms were being used as a youth hostel.

A return visit with my father in 2015 revealed a town that had been refreshed and modernized, boasting old-world European charm perfect for a quiet getaway. Everything was bright and shiny. The Schloss, still a hostel, had been restored; and its updated museum, now inside the castle, had become a popular site, especially for British tourists, offering comprehensive tours by knowledgeable guides.

Advertisement