The 29th (Canadian) Motor Torpedo Boat Flotilla conducts an exercise in May 1944. Weeks later, it would participate with the British during the invasion at Sword Beach on D-Day [LAC/3204508]

We all know the story, or at least a version of it.

The success of D-Day on June 6, 1944, was the result of a combined arms operation spearheaded by U.S., British and Canadian forces. These three Allied nations, the oft-cited tale goes, were assigned five heavily defended sectors between them.

The British were tasked with landing at the beaches codenamed Sword and Gold; the Americans took on the mantle of assaulting Utah and Omaha beaches; and the Canadians squared off against German resistance on Juno Beach.

Except, contends historian and archeologist Stephen Fisher, it’s not—and never has been—that straightforward.

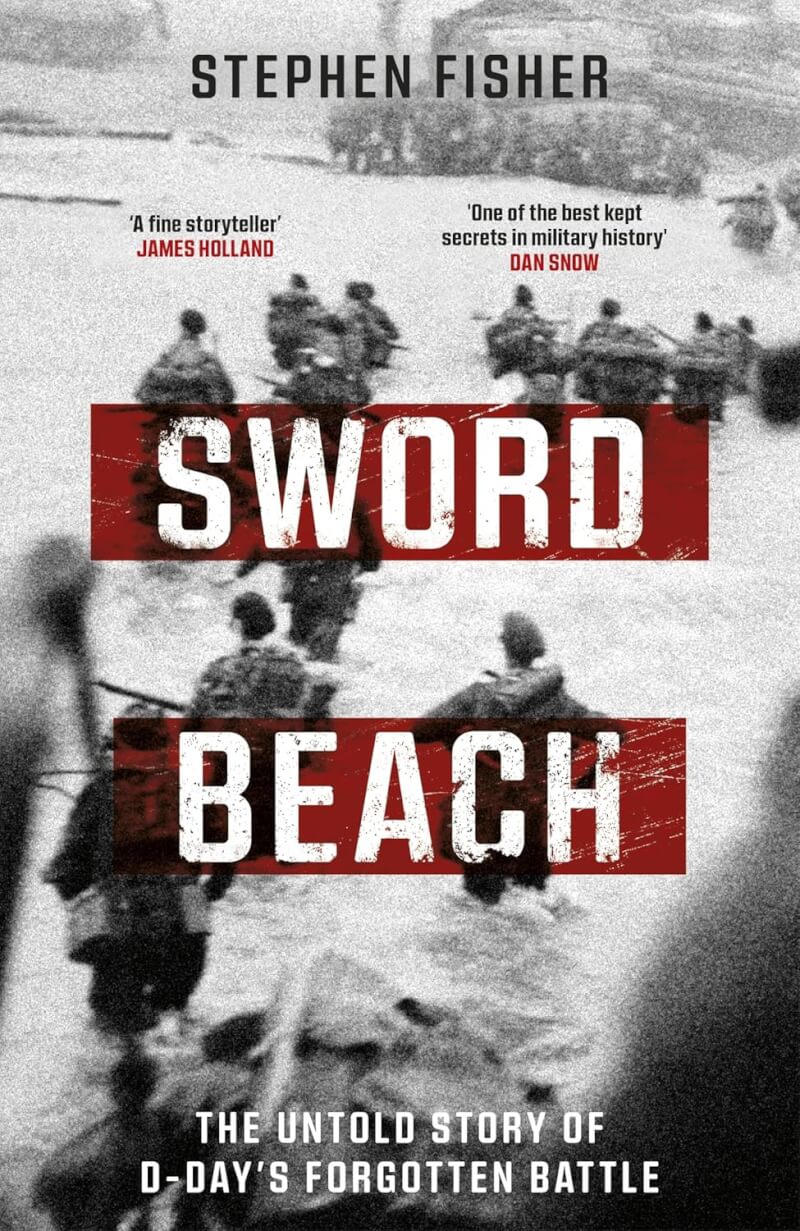

The British author of Sword Beach: The Untold Story of D-Day’s Forgotten Victory, published in 2024, firmly believes that “you can’t just pigeonhole the beaches by nationality,” arguing for a lens-widening within public discourse.

Forgotten is indeed the word for those Canadians, among others, who supported the landings recounted in Fisher’s latest book. Here, in a Legion Magazine exclusive—the first of two parts—he highlights that unsung contribution.

Historian and archeologist Stephen Fisher’s latest book Sword Beach: The Untold Story of D-Day’s Forgotten Victory includes details on the role Canadians played in that sector on D-Day. [Bantam Books]

On his reason for writing the book

I’ve done a lot of research on landing craft in the past. My first landing craft project was some 15 years ago now, with LCT 2428, which sank just off the south coast of England very late on June 5, 1944.

It had sailed with Force J, which was bound for Juno Beach carrying two Centaur tanks of the Royal Marines Armoured Support Group, but it sank en route after its engines broke down. All crew members made it off safely, and the landing craft deposited its two tanks upside down on the seabed, where they’re still in pretty good condition.

We were tasked with looking at the feasibility of legally protecting the site, which it now is, I’m pleased to say.

Anyway, over the years, I became quite adept at researching landing craft on D-Day, and I eventually decided to compile them all to create a useful record, a reference book. It wasn’t long until I realized that I’d probably need to break this down beach by beach, so I started with Sword.

But then I realized that I couldn’t write about the landing craft without talking about the troops inside them. One thing led to another, and before I knew it, I realized it was turning into a book about Sword Beach overall.

On telling stories of people

When I started writing [the book] originally, I was still anticipating it being a reference work. But when I truly got into the story, I remembered that I could write half-decent prose. You forget that when you become used to writing archeological reports.

Instead of, “‘A’ Company advanced to Y objective, captured X many prisoners of war, and sustained so many casualties,” it was more along the lines of, “Lieutenant Commander [Edmund] Currey stared through bloodshot eyes on the distant beach as the smoke of Hades rolled across the sand and over the surf in front of him.” That sort of thing.

I was still, of course, being accurate, as so many accounts talk about how the beach bombardment unleashed a thick cloud of smoke and dust. Equally, it was fair to say that Commander Currey had bloodshot eyes because in the report he wrote later, he mentioned that he’d been up all night on Benzedrine tablets. He hadn’t slept for about 36 hours by that point, so of course he’s going to have bloodshot eyes.

Knowing what I do about military history, I was able to weave these sorts of details into the story to set the scene. Rather than the company advancing down the road, I talk about the soft flapping of webbing and the hobnail boots rattling on the tarmac.

On the Canadians at Sword Beach

The one thing lacking from the Canadian contribution on Sword Beach is an organized army unit. We have Canloan officers [short for “Canadian loan,” referring to Canadian lieutenants and captains seconded to the British Army ranks], but we don’t have a battalion or company of Canadian troops.

What we do have, though, is the [Canadian] airborne, which accidentally comes to Sword and, indeed, are the very first people to land in the area.

At least two sticks [broadly, a group of paratroopers exiting an aircraft at around the same time] of about 10 men each from 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion—both from ‘C’ Company—found themselves in the region of Colleville-sur-Orne, now Colleville-Montgomery.

Lieutenant John Madden of 9 Platoon, the commander of one of the sticks, was later stunned when he found out how far he was from his drop zone. He and his men had a brief encounter with a German on a bicycle, and they killed him before running for it because they’d alerted a nearby farmhouse. By that stage, however, the Germans were already alert to what was happening at the front.

He ultimately hangs out with the Suffolks [1st Battalion, Suffolk Regiment] for a while, helps with the attack on [strongpoint] Hillman, and then breaks off to make his way to Pegasus Bridge and over to join his unit, arriving on the 7th.

Lieutenant John Madden of 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion helps load a Universal Carrier into a Royal Air Force glider in preparation for an operation in March 1945. On D-Day, Madden commanded a group of Canadian paratroopers that landed in the Sword Beach sector. [LAC/3524473]

On the Canadian air contribution

This is where we have an organized Canadian unit in a sense, an actual formation that takes part in the landings at Sword—in fact, that takes part in the landings on all three Commonwealth beaches.

Among the Royal Canadian Air Force squadrons at Sword—and there are others—is 440 Squadron, and they’re tasked with striking beach targets just before the landing craft touch down.

You’ve got around 12 Typhoons under the command of Squadron Leader William Pentland. Just as the ships are easing off their bombardment, these aircraft drop their bombs in sequence over strongpoint Cod before flying onto their secondary objective, which they strafed. That’s effectively the final attack before the British 3rd Infantry Division landed.

On Canadian naval efforts that night

There is also another Canadian formation off Sword Beach on the night of D-Day. Elements of the Royal Canadian Navy’s 29th (Canadian) Motor Torpedo Boat Flotilla were tasked with providing escort and offshore protection for the fleets gathering there.

The flotilla was commanded by Lieutenant Commander Anthony Law, which was joined by the British 55th Motor Torpedo Boat Flotilla in its duties, itself commanded by Lieutenant Commander Donald Bradford. Together, they defended the eastern end of Sword anchorage, facing Le Havre, where all the German warships were based.

They did encounter action that night when several German R-boats [minesweepers] came out to start laying mines. Law and Bradford both took turns engaging these boats.

This carried on night after night after night. Actually, Law and his flotilla became involved in defending the area for weeks, months after the landings.

It’s part of the D-Day story that often gets forgotten.

On the multinational elements of D-Day

The Canadians are represented in every aspect at Sword Beach, from the navy to the army [namely, through Canloan officers] to the air force and, yes, accidentally, even through the airborne.

But it’s important to remember that there were so many nationalities involved. You have the Norwegian perspective. You have the American perspective. You have the Polish perspective. You have the French perspective and more.

Obviously, the dominant force at Sword Beach was British. There’s no getting away from that, as it’s a British infantry division landing, supported by a large contingent of the British Royal Navy.

Equally, though, that fact brings up a good point. The only reason we assign our nationalities to these beaches is because of the landing division. Thus, we see Sword and Gold as British because it’s the [British] 3rd Infantry Division and the [British] 50th Infantry Division landing at them, respectively.

Obviously, we see Juno Beach as Canadian because of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division.

And the same goes for the American divisions landing at Omaha and Utah.

The reality is that every beach was multinational, and I think it’s unfair to claim otherwise. We oversimplify D-Day to our own detriment.

This abridged interview has been edited for brevity and clarity. A second part will appear next week, on Nov. 12.

Advertisement