An oil painting of a U-boat by Augusto Ferrer-Dalmau. Winston Churchill once said the U-boat peril was the only thing that truly frightened him during the Second World War. [Wikimedia]

But it was a different sort of ground-shaking event: the beginning of the Battle of the St. Lawrence, which would rage in Canadian home waters for more than two years.

Rushing to the seaside, some residents of Cloridorme, Que., could see offshore lights vanish in the black of the night: German submarine U-553.

In early May 1942 Kapitänleutnant Karl Thurmann guided the U-boat from the Gulf of St. Lawrence into the wide mouth of the river. It was the sub’s seventh patrol. In the previous 11 months, it had sunk five ships and damaged one.

On May 10, the sub was spotted off the Gaspé coast, but eluded bombs dropped by a Royal Canadian Air Force Catalina aircraft and submerged, undamaged. That same day, two cargo ships left Montreal for Sydney, N.S., where they were to join a convoy bound for Britain.

A Royal Canadian Air Force Catalina. Catalinas were a staple of Allied maritime aviation during the war. [RCAF/James Craik]

Just before midnight on May 11, the freighter came into the sights of the submarine. After the torpedo hit Nicoya, Captain Ernest Henry Brice immediately ordered crew to come on deck and the code for submarine attack was transmitted.

When it was apparent the ship was sinking, those aboard leapt into the water, where they clambered onto two lifeboats and a raft. Then U-553 fired a second torpedo. Nicoya’s captain said he saw six men climbing onto a raft near the ship when the second torpedo hit, and they were not seen again.

While the survivors began their cold night on the water, U-553 continued to prowl.

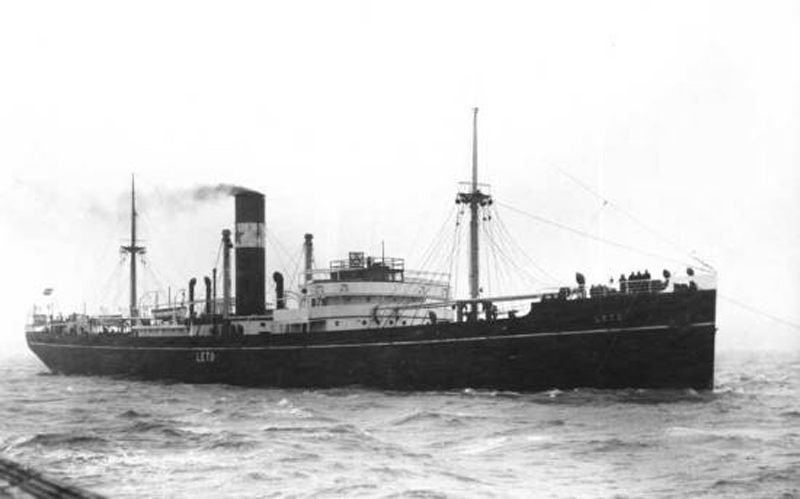

Just after 2 a.m. on May 12, the submarine sighted the Dutch freighter Leto, carrying 39 crew and four passengers. “We never used watches in the Saint Lawrence River and we were only due to start them the morning after we were sunk,” one of the gunners later reported.

A torpedo hit the ship amidships; Leto sank in 12 minutes, with a loss of 12 lives. There had been no time to send a distress signal.All the lifeboats had been smashed; 22 survivors crowded into a jolly boat designed to carry a dozen and bailed for their lives.

Passing ships spotted the boat at about 5 a.m., and another dozen men were plucked from the water, one so far gone he died of exposure.

Prior to the loss of these ships, cargo vessels had sailed unescorted from Quebec to Nova Scotia, but after May 21, escorts in convoys plied the Montreal-Sydney route.

In June, the Gulf Escort Force was organized, growing to a force of 19 vessels by September, including seven corvettes, five Bangor-class minesweepers and half a dozen motor launches.

By the time the Battle of the St. Lawrence ended, German U-boats had sunk two dozen ships, including three merchant vessels and four warships. Among the losses were HMC ships Charlottetown, Racoon and Shawinigan, and the ferry SS Caribou, with the loss of 137 lives, many of them women and children.

Advertisement