There is perhaps no place in France where as many men have been killed to the square yard as on this sloping ground,” recounted Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Hayes of the 85th Battalion of the Vimy Ridge battlefield. The ridge in northeastern France was a crucial high point that offered a commanding view of the surrounding countryside. In the static trench warfare of the Western Front, it offered tremendous advantages to whichever side occupied it.

The German Sixth Army had swept over French forces in October 1914 and captured the seven-kilometre-long ridge. It was 145 metres above sea level at its highest point, giving the Germans long-range observation into the French soldiers’ trenches. They used their artillery to devastating effect. The French tried to retake the ridge in three major battles in 1914 and 1915 but were hurled back each time.

Some 400,000 French and Germans were killed or maimed in those see-saw fights, and the bloody action of attack and counterattack ensured that countless bodies of the slain were minced to rotting meat and shards of bone. Major C.A. Bill of the 15th Royal Warwickshire Regiment, a British regiment that was briefly at the Vimy front in 1916, recounted, “In the rough grass just behind our front lines I came across a long line of Zouaves who had been mown down like a swathe of corn while advancing in the open, and from the condition of the bodies they must have been lying out there for 12 months.” The gagging stench of decomposing bodies caught in the throat for kilometres in all directions.

The Germans steadily fortified the ridge, which acted as a breakwater in that part of France, protecting the all-important coal-producing area of Lens to the northeast. Kilometres of zigzagging trenches were anchored with concrete pillboxes that housed MG-08 machine-gun teams. Artillery crews and mortar teams had mapped out the areas of advance. It is no wonder the Germans were confident that they could hold the ridge against any attack.

The Canadian Corps was the country’s primary fighting formation on the Western Front. By late 1916, when the Canadians arrived at the Vimy front, the corps was about 100,000 strong. Commanded by Sir Julian Byng, an experienced and well-liked British general, the corps had four infantry divisions, each of about 20,000 soldiers, with the remaining soldiers attached to the corps. The Canadian soldiers soon took to calling themselves the Byng Boys, a nod to both a popular theatre show in London and the popularity of the corps commander. “He was literally adored by the men,” wrote Lt.-Col. Andrew McNaughton.

The bulk of an infantry division consisted of infantry, with 12 battalions of 1,000 men each, although rarely were they up to strength due to the constant wastage at the front. Machine-gun units, artillery, engineers, labour battalions, medical ambulances and a host of other support units formed the rest of the division, which was commanded by a major-general.

The Canadian fighting record had been uneven up to late-1916. While Canadians had responded enthusiastically to the call of war in August 1914, with thousands flocking to the colours, it had taken time and considerable effort to transform the militias and groups of men into coherent fighting units. But many of the First Contingent Canadians, as the first 30,000 or so to go overseas were known, had militia experience or service in the South African War. Whatever a man was before the war, they were all Canadians now as they fought under the Maple Leaf symbol.

The Canadian Division had made its name at the Second Battle of Ypres in April 1915 when it withstood the first chlorine gas attacks and overwhelming German forces. The battle cost more than 6,000 casualties, but the Canadians were lauded throughout the empire.

That summer, fall and winter saw the Canadians hold the line, with a new division arriving to create, in September 1915, the Canadian Corps. The corps was Canada’s identifiable fighting unit during the war and Canadians and politicians argued that the dominion’s divisions, eventually reaching four, should fight together and not be divided and transferred to other British corps and armies. This allowed the Canadians to serve and fight together.

The Canadians, like all forces, had been badly bloodied on the Somme, and had limped off with 24,000 casualties.

They moved to the relatively quiet Vimy sector where they took over the old French trenches, recently held by British troops. The new soldiers who arrived to fill the ranks of the shattered battalions talked roughly of knocking the Germans back, while the old soldiers held their tongues. Fortress Vimy would not fall without a titanic struggle.

A Highlander regiment boards a vehicle at Vimy Ridge in April 1917. [DND/LAC/PA-001197]

The corps was Canada’s identifiable fighting unit during

the war and Canadians and politicians argued that the

dominion’s divisions, eventually reaching four, should

fight together and not be divided and transferred to

other British corps and armies.

Early in 1917, during one of the coldest winters in modern memory, Sir Julian Byng appraised Vimy Ridge. He did not like what he saw. The survivors of the Somme were familiar with flat farmers’ fields. The few minor ridges, hills and cutbacks of the Somme were dwarfed by the ridge that loomed like an enormous compost heap of scorched earth and dead things.

The terrain rose steadily from southeast to northwest, with the highest point being the heavily fortified Hill 145. To the north of Hill 145 was a foul-smelling lowland marsh that was overlooked by The Pimple, a high position that had been tunnelled to create reinforced trenches and dugouts. The defenders there could sweep much of the Canadian front-line trenches to the south and southwest, opposite Hill 145. “The Germans captured Vimy in October 1914 and erected strong defences,” recounted Canadian gunner Allan Cole. “They considered the Ridge impregnable…. Concrete gun and machine-gun emplacements dotted the area and every provision had been made for defense.”

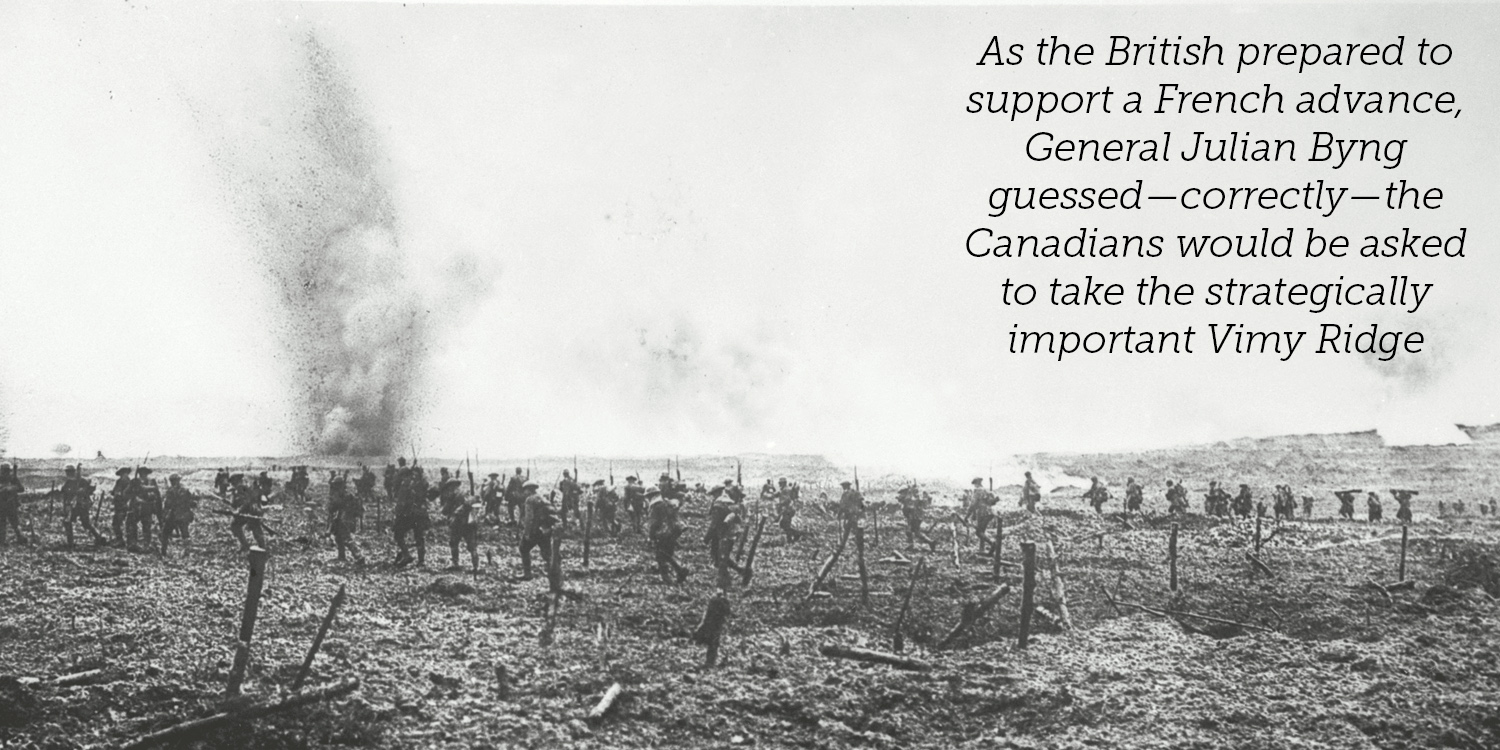

The Canadians served as part of General Henry Horne’s First Army, and Byng suspected—rightly it turned out—that his Canadian Corps would be ordered to capture the ridge. He turned to his senior staff officers and commanders for a plan.

Vimy Ridge could not be outmanoeuvred. Any attack would be a frontal assault against a prepared positon.

The complex fire plan would be organized by Major Alan Brooke, a 34-year-old professional soldier with a sharp mind. Brooke devised a plan of steadily bombarding the German defences along the ridge and then, on the day of battle, to lay down a creeping barrage of shellfire that would rake through the enemy lines, tearing up the German defences and driving defenders into their dugouts.

Andrew McNaughton, the Canadian counter battery officer, was responsible for using the siege guns from Brigadier Roger Massie’s heavy artillery—howitzers above a six-inch calibre—to harass, destroy and suppress enemy guns.

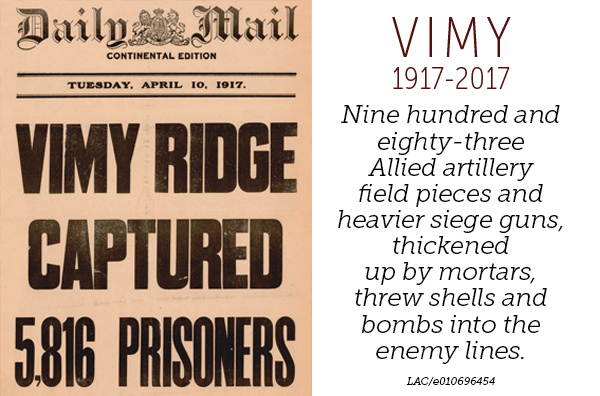

The bombardment and counter battery fire would be delivered by British and Canadian gunners. There would eventually be 983 guns and mortars to shatter the enemy lines. To feed the guns the Canadians had 1.6 million shells. New light-rail lines were laid by engineering, railway, pioneer and infantry units. Roads were created and continually rebuilt as they dissolved under the steady tramp of the hooves from 50,000 horses and mules. The animals suffered from overwork and shortages of fodder. “Dead bodies of the poor beasts lie all over the place,” lamented Major Karl Weatherbe of the 6th Company, Canadian Engineers.

The Canadian Corps’ attack on Vimy was not in isolation. It was part of the larger British Arras offensive, which in turn was in support of a French-led offensive on the Aisne River front. French General Robert Nivelle, newly appointed to command the French armies after his success during the Battle of Verdun the previous year, had promised politicians, his soldiers and all of France that he would deliver victory. His pride and bluster verged on lies, and his plans were no different than other blind bashing affairs, except that his control over the proposed operation was pathetically bad. The Germans captured his plans and knew exactly where he aimed to attack. They prepared accordingly, and even retreated along the front to better trenches 30 kilometres to the rear, which allowed for the grouping of more reserve formations and artillery.

Nivelle’s charm also convinced the new British prime minister, David Lloyd George, that he had found the solution to the deadlock on the Western Front. Lloyd George had agonized over the Somme casualties, and he was all too happy to let the French do the attacking and dying in a new push against the enemy. But he also despised his battlefield commander, Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig. He ordered Haig to fall into line and support Nivelle, even though the British general was wary of the French plan.

General Edmund Allenby’s Third Army and General Henry Horne’s First Army would attack a week in advance of the French to draw off German reserves. The strongpoint of Vimy Ridge was in the British sector and Haig feared it, knowing the ruin that had befallen French armies there in the past. But Vimy had to fall or the British push would likely be stopped. There was extreme pressure on Byng’s Canadians to succeed.

Canadian soldiers lay a road in preparation for the coming battle. [DND/LAC/PA-001226]

Roads were created and continually rebuilt as

they dissolved under the steady tramp of the

hooves from 50,000 horses and mules.

After the Somme, Byng ordered an intense study of its successes and failures. There were more of the latter than the former. Byng also selected his best general, Major-General Arthur Currie, to go on a study tour with the French and British. Currie had been a prewar militia officer and land developer from Victoria, but he had a good mind for warfare. He had read widely and was willing to accept that he did not have all the answers to the riddle of the trenches. But he was willing to learn.

When he returned to the corps, his detailed report became an important blueprint for revolutionizing the Canadian way of battle. For the infantry, French lessons at Verdun showed the importance of decentralizing command and up-gunning the infantry. They had to have more firepower. The platoon of 50 or so men was reorganized to have four sections: riflemen, grenade throwers, rifle grenadiers and Lewis machine-gunners.

The infantry also worked closer with the gunners who were to lay down the creeping barrage. Infantrymen practised behind the lines, moving to flags that represented the imaginary barrage, leaping forward 100 yards every three minutes. During the advance, officers were instructed to lie down ‘dead’ so that more junior ranks were forced to take over. Then they were ‘killed’ off. The drive was to continue relentlessly. Large-scale models, some more than a dozen metres wide, were studied, as were aerial photographs. Some 40,000 individual maps were also issued, so that almost every man had one.

The training was put into practice in the form of raids on the German trenches. Raiders shed most of their bulky equipment, armed themselves with wicked-looking knives, trench clubs and revolvers, and set off across no man’s land to pinch a German prisoner or toss a few grenades in a trench.

These hit-and-run operations left the front agitated, and long before the Vimy battle the Germans had learned to fear the Canucks. Byng liked the raids—60 were unleashed before the assault on the ridge over a three-month period—because he thought they inculcated aggression and skills, while also setting the enemy on edge and allowing for the gathering of intelligence. But some of the senior officers, like Currie, thought the Canadians were engaged in too many raids, with casualties befalling the best and most forceful soldiers. There were spectacular victories but also harsh rebukes, like a 4th Division raid on March 1, where four battalions of attackers relied on gas instead of artillery fire, and suffered 687 killed and wounded in the poorly planned operation.

There were even more losses from German shellfire. Robert Edwards wrote to family friends in Malahide Township: “This is a terrible war. … Even when going in the trenches, labouring under a heavy load, they are facing death all the way as one never knows whether they may see us and open a machine gun on the party and wipe them out.”

In the last week of March, the Allied artillery began more intense bombardments, and the ferocity ratcheted up again on April 2. Over a million shells were fired.

The German lines were pulverized in drumfire bombardments, with the defenders killed or forced to cower in their deep dugouts. The new 106 fuses aided in the destruction of wire, as their sensitivity allowed shells to explode on contact as opposed to burying themselves in the ground. The fuses were one of the more important technological evolutions during the war and the wire was systematically cleared. “Our ammunition and guns now seem to be unlimited,” Captain Victor Tupper of the 16th Battalion wrote only a few days before his death in battle. “We are hammering Fritz to pieces.”

“This is a terrible war.… Even when

going in the trenches, labouring

under a heavy load, they are facing

death all the way as one never

knows whether they may see us

and open a machine gun on

the party and wipe them out.”

About 15,000 Canadian infantrymen from 21 first-wave battalions filtered toward the front on the night of April 8-9. The lucky ones went into one of the 13 underground tunnels. They were dark and claustrophobic, and some seemed impossibly long, such as Goodman that ran 1,722 metres, but they offered protection from shellfire and the harsh weather. The temperature had dipped below freezing and the early hours of the 9th were miserable, with periodic snow squalls blasting down from the ridge.

The Canadians were rested and ready. While the raids and enemy shellfire had killed and injured several thousand over the previous three months of intense preparation, most infantrymen felt better prepared than ever before. But that did not mean they were naïve. No one expected the German fortress to fall easily.

Men talked about their fate. Most shrugged off the thought of death, with the nonchalant phrase, you’ll get it “when your number’s up.” But no one wanted to die. Outward calmness covered the internal battles that raged. Most men wrote last letters to loved ones, or private notes in their diaries in case their bodies were found. Lieutenant Jack McClung of the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry was 19 years old and the son of the activist and author, Nellie McClung. Jack had left the University of Alberta to enlist the year before and now he faced the grave uncertainly of combat for the first time. He confided his thoughts to his diary: “Easter Sunday night & we go over the top tomorrow morn at 5:30. I guess a fellow has more sensations & feelings in this short night than in his whole life…. Each of us is trying to hide the real state of his mind. I know how much I am thinking about Mother, Dad and all the kids.”

Further to the rear, but no less anxious, Byng’s headquarters staff studied maps and hoped that the intelligence was correct. The Germans had three divisions along the front: 1st Bavarian Reserve Division in the south (up to Thelus), the Prussian 79th Reserve Division in the centre (and covering Hill 145 and a sector to the south opposite the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division), and the 16th Bavarian Jaeger Infantry Division in the northern sector. There were about 8,000 infantrymen on the ridge or to the immediate east, all dug in to deep trenches and dugouts. Despite the obvious preparation, the Germans had not rushed reinforcements to the front. There was not a lot of room in which to garrison more men, and the ridge was expected to hold out for several days. The plan was that the German reserve formations would begin to march as soon as the battle was unleashed, and so the Canadians would have to attack fast and hard.

For the first and last time in the war, the four Canadian divisions would assault together. On the right was Currie’s 1st Division. Next to it was Maj.-Gen. Henry Burstall’s 2nd Division. These two divisions had the farthest to go on the irregular battlefield, with Currie’s men driving over 4,000 metres. Because Vimy Ridge sat unevenly along a northwest-southeast axis, and was broad in the south and narrowed to a high point at Hill 145, the Canadians on the right had to go deeper than those on the left. The 3rd Division, commanded by Maj.-Gen. Louis Lipsett, faced a higher point on the ridge, and the front was riven with dozens of deep mine craters from years of underground warfare. On the far left, Maj.-Gen. David Watson’s 4th Division faced the highest point of the ridge, with the heavily fortified strongpoint of Hill 145 (where the Vimy monument stands today). The 4th Division had 700 metres to advance, although almost every step was uphill.

The 15,000 Canadian infantry, followed by thousands more in the succeeding waves of attack, would follow a creeping barrage. That made the operation a timed one. Because of the distance on the right, the 1st and 2nd Division’s had four objectives, labelled the Black, Red, Blue and Brown Lines. Each was to be attacked at a preplanned time, starting at 5:30 a.m., with pauses on the line while artillery shells rained down on the Germans before the creeping barrage set off again. The 3rd and 4th Divisions faced a higher and narrower front, and had only two lines to capture. The fighting was expected to extend to early afternoon, with at least eight hours of fierce combat.

As the minutes ticked down on the synchronized watches of hundreds of officers along the front, infantrymen attached bayonets to their Lee Enfield rifles. Those in the tunnels gathered toward the eastern exits, waiting for the entrances to be blown out, while the men in the trenches shivered and stamped their cold feet. Two minutes before zero hour—the time of the attack—230 Vickers machine guns opened fire on the enemy lines, spraying tens of thousands of .303 rounds over the front. The goal was less to kill Germans than to keep them in their dugouts.

At 5:30 a.m., with dark skies that swirled with snow, a storm of steel hurled down. Nine hundred and eighty-three Allied artillery field pieces and heavier siege guns, thickened up by mortars, threw shells and bombs into the enemy lines. A series of mines also blew under the defenders. McNaughton’s heavies targeted enemy batteries, working closely with the observation aircraft above that circled the front looking for telltale signs of guns firing.

From the trenches and tunnels emerged the Canadian infantry. The cacophony of noise was shocking. Officers tried to scream commands but nothing could be heard above the din of shells overhead that sounded like trains passing in continuous runs.

Lieutenant Gregory Clark of the 4th Canadian Mounted Rifles enlisted at age 26, having left behind his journalist position at the Toronto Star. He wrote of the shocking shellfire: “I had seen something of the terror, the vast, paralyzing, terrific tumult of battle: a thing so beyond humanity, as if all the gods and all the devils had gone mad and were battling, forgetful of poor, frail mortals that they tramped upon.”

The Canadians marched forward into the explosions. The creeping barrage set off toward the enemy lines, leaping 100 yards every three minutes. It was effective along most parts of the front, tearing up the enemy lines and driving Germans into the dugouts. Hundreds died in the shellfire; others were buried alive.

Some platoons had to fight their way forward to the Black Line, others merely marched to their objectives. The blood sacrifice was usually paid when a number of German machine guns survived and could fire into the advancing Canadians. The Black Line, about 700 metres to the east, was captured around 6:10 a.m.

The Canadians occupied the shattered German trenches and allowed the artillery to do its deadly work on the enemy positons in a standing barrage for about half an hour. At 6:45 a.m., the creeping barrage moved off again.

The battalions on the 1st and 2nd Division’s fronts made good their second objective, the Red Line, by around 7:15 a.m. They surged past the German dead, but left behind a wave of khaki-uniformed corpses and injured men. Despite the barrage, some Germans continued to fire even as the shellfire raged around them.

The official reports make note of the resolute fighting by the Bavarian troops on this front. They “fought to the last,” noted one Canadian officer, “showing no inclination to surrender.”

Following behind the first units were follow-on companies that cleared strongpoints that had been bypassed by the lead units. This was known as “mopping up” the enemy, most of whom were holed up in their deep dugouts. Germans were ordered from the dark caves. Those who did not climb the stairs hastily, hands raised and weapons downed, were often killed by grenades thrown in.

The disarmed prisoners, sometimes groups as large as several dozen men, were sent to the rear, but this was a dangerous time for the Germans, as some were killed by their own shells and others were shot by scared or vengeful Canadians who were pushing forward in the secondary waves. Prisoners learned that their lives were more precious if they carried in wounded Canadians, and hundreds volunteered for the back-breaking work.

Disarmed German prisoners move to the rear past Canadian soldiers. [DND/LAC/PA-001128]

While the 1st and 2nd Divisions faced two more lines of objectives beyond the Red Line, 3rd Division clawed its way to its final objectives in about 90 minutes of battle and dug in to hold the new positions. Like on other divisional fronts, Vickers machine-gun teams rushed forward, barbed wire was uncoiled, and sandbags were filled to build new trench systems. After hard battle came hard labour to protect against expected counterattacks.

The 4th Division faced the toughest objective on the ridge: the enemy strongpoint of Hill 145. Elite Prussian troops garrisoned the position and they had mapped out every avenue of advance, clearing obstacles for good fields of fire and laying stakes for mortar teams to shoot from map grids.

The division’s first-wave battalions—four in total, but backed up by several more—ran into immediate trouble at zero hour. The creeping barrage pulverized much of the German line, but a trench about 365 metres from the Canadians was deliberately left unhit. Brigadier Victor Odlum, commander of the 11th Brigade and a respected officer, made the wrong decision to call off the artillery. He had hoped the trench could be captured undamaged and then used as a forward operating base.

“They had machine guns and were slaughtering us,” remembered one Canadian. The torrent of small-arms fire was devastating. Other German defenders farther up the hill survived the barrage and fired into the ranks of the advancing Canadians. One German report noted that the Canadian “corpses accumulated and formed small hills of khaki.” Ninety minutes of fierce battle left Watson’s soldiers spread out in the mud of no man’s land, with the Prussians holding most of the positions. The situation was dire.

Farther to the south, the 1st and 2nd Divisions completed their drives to their final positions on the third and fourth lines, starting at 9:35 a.m. They had faced a tough objective on a high point known as Hill 135, but supporting Tommies of the 13th British Brigade overran the position and held it fiercely. The eight tanks assigned to the 2nd Division could not overcome the cratered terrain, and all of them broke down rapidly or were knocked out by shellfire. The 1st and 2nd Divisions surged to the final objectives, the Blue and Brown lines, with heavy fighting until about 2:00 p.m., when final resistance crumbled.

Captured German soldiers help carry in a wounded Canadian. [DND/LAC/PA-002060]

“I had seen something of the terror, the vast, paralyzing,

terrific tumult of battle: a thing so beyond humanity,

as if all the gods and all the devils had gone mad

and were battling, forgetful of poor, frail mortals

that they tramped upon.”

With the divisions to the south on their final objectives, the 4th Division was in trouble. The advancing battalions were pinned down and strung out in the mud below Hill 145. General Watson had only one final infantry battalion to throw into battle. The 85th Battalion from Nova Scotia was relatively new to the front. Two companies were ordered forward in the afternoon to salvage the situation. The worry was that the Germans might hold Hill 145, even though the rest of the ridge had fallen to the Canadians, and then launch counterattacks from there to roll up the southern flank. The fortress of Hill 145, along with the high point of The Pimple to the north, had to fall or the Germans might snatch victory from the jaws of defeat.

The two companies of Maritimers filtered into the front lines. Unknown to them, General Watson and the battalion commander, Lt.-Col. A.H. Borden, upon studying the situation and consulting the artillery, felt compelled to call off the supporting barrage. The front was too unstable, with soldiers spread over the battlefield, half-submerged in the craters or mud. To fire a heavy bombardment would kill too many Canadians. A runner was sent forward to inform the 85th Battalion’s company commanders, but only one received it before the time of the attack.

A few minutes before 6:00 p.m., the infantry attached bayonets. Shoulders were hunched in anticipation as watches struck the zero hour. No sound. No shells. To assault a fortified trench without a barrage at this stage in the war was nothing less than suicide. But the strongpoint had to fall. The officers slowly raised whistles to lips. The shrill sound of attack rang out. The infantrymen scrambled from the rough trenches to charge into the enemy trenches.

On the other side of no man’s land, the Prussians were taking a much-needed break. They had fought all day and been shelled relentlessly. The battle seemed won. Exhausted soldiers, dozing or staring off into nothing, many in deep dugouts, were roused by the sound of sentries’ alarms, stray Mauser shots, and then the unmistakable chugging of the MG-08 heavy Maxim as it opened up its death rattle.

The Maritimers charged across the pitted, muddy field. Canadians were punched down from the bullet fire, their cries of agony heard within the strange silence of the battlefield without shellfire. But the 85th did not falter. As they closed on the enemy, they let out a war cry. And then they crashed through the German lines, bayonets first. A mad battle of shooting and stabbing left dozens of Canadians and Prussians dead and dying. A few of the defenders broke ranks, fleeing for their lives; like a fast-moving plague, others were infected, and followed. Within 10 minutes the Prussians were routed.

Hill 145 fell to the Canadians and the last strongpoint on the ridge was in Canadian hands as the sun went down. At 3:15 p.m. on the 10th, after a miserable night of cold, snow and shelling, the 44th and 50th Battalions drove the remaining defenders back from the lower eastern slope in a sharp but short clash.

Victory had not come lightly. Sergeant Ernest Black recounted the appalling scene from atop the ridge: “The whole thing was a clutter of smashed guns and wagons, dead horses and dead men.” When the corpse-counters were done their grisly work, they found that 7,700 Canadians had been killed and wounded on the 9th and 10th.

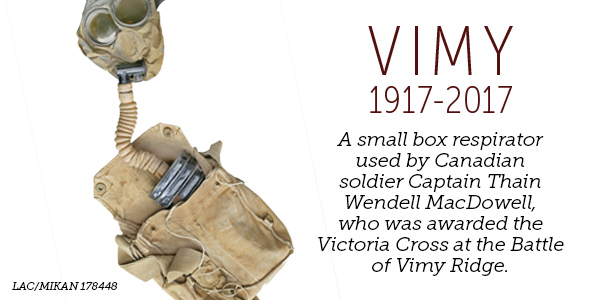

Those who survived faced ghastly wounds. Bullets and shrapnel tore flesh and pulped bones. Most of the gaping, bloody holes were packed with mud and dirty clothing, all of which was impregnated with microbes. Festering wounds were difficult to clean in the age before antibiotics, and surgeons farther to the rear often cut away shredded flesh, hoping to stay ahead of the infections. An unknown but large number of soldiers died of their wounds or from infection in the weeks or months after the battle. Those losses are not formally counted as part of the Vimy battle.

On the 12th, the Canadians completed their victory over the Germans on their front. Three depleted and tired Canadian battalions attacked the strongpoint of The Pimple, to the north of the ridge. Fresh Prussian troops had been rushed to garrison the position, in the hope of salvaging something of the defeat on the ridge. They were ready for an attack. But the Canadian assault at 5:00 a.m. in a heavy snowstorm, behind a heavier creeping barrage, shattered the elite German forces from the 4th Guards Infantry Division.

The Sixth Army commander despondently gave the order to pull back his troops to existing trenches, about seven kilometres from Vimy and out of range of Allied shellfire.

Their defeat was complete.

Victorious troops celebrate as they are transported away from the Vimy battlefield. [DND/LAC/PA-011270]

From the start, the seizing of the ridge was acknowledged by Canadian soldiers as something unique. While many infantrymen simply collapsed from the ordeal into a deep slumber after their reward of rum and a hot meal, others wrote in diaries and letters home about their impressions.

The spoils of war were considerable—more than 4,000 German prisoners were captured, and thousands more were killed, wounded or sent fleeing to the rear. Captured arms included 63 enemy guns, 104 trench mortars and 124 machine guns.

Four Victoria Crosses were awarded to Canadians for uncommon valour, three of them posthumously. Hundreds of other gallantry medals were also distributed. But many acts of bravery went unrecognized.

The celebration was cut with grief. The four-day battle cost 10,602 casualties, of which 3,598 were fatal. In fact, the first day of battle, where most of the ridge was overrun, is the single bloodiest day in Canadian military history. Yet Vimy was never depicted as a senseless bloodbath. The capture of the ridge in the face of previous French defeats allowed for considerable crowing.

While British First Army had supplied about half the artillery, two battalions of combat troops and thousands of soldiers to engage in logistical work, the British were soon erased from the Vimy story. Vimy was framed as a Canadian victory. Yet, it should be noted, it was the Canadian infantry and machine-gunners, supported by medical and engineering units, who did the vast bulk of the fighting and dying. But even Sir Julian Byng, the British general who commanded the Canadians, was forgotten in the post-Second World War period. It was—and remains—not uncommon to hear the erroneous assertion that it was Arthur Currie who commanded the corps at Vimy. He didn’t, but it seems plausible to many since Vimy was held up as an iconic event in Canadian history.

Vimy is remembered as more than a battle. The placing of Canada’s overseas memorial on Vimy Ridge further raised the sense of Vimy’s importance. King Edward VIII’s unveiling of Walter Allward’s stunningly beautiful monument on the ridge on July 26, 1936, before more than 6,000 Canadian veterans propelled the idea of Vimy forward. It was seen as more than a battle.

Around the 50th anniversary of the battle, in the mid-1960s, a series of books was published on the battle and it became more common to hear that Vimy was the ‘birth of the nation.’ That Canadians fought there from across the country created a built-in narrative that further raised Vimy’s importance. Canadians had done something great, together.

Nations choose symbols, and Vimy is an important one for Canada. Tens of thousands have returned to the site of the battlefield in formal and informal pilgrimages. To stand at the memorial on Canada’s ridge in France, as thousands of Canadians will do this year on the 100th anniversary, is to feel the weight of history, the echoes of the clash of battle, and the faint voices of those who served and sacrificed.

Advertisement