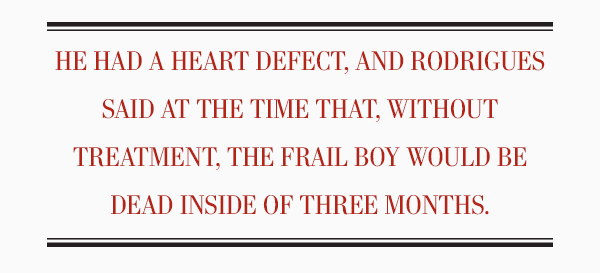

Nine-year-old Djamshid Djan Popal and his father Shafiullah wait in the airport at Kabul, Afghanistan, on Thursday, July 1, 2004, minutes before beginning their journey to Canada. [CP PHOTO / Stephen Thorne]

It might be wise to remember this as Canadian troops ramp up their peace operations in Mali, where they are conducting medical evacuations on behalf of United Nations forces trying to intervene in

an al-Qaida-driven insurgency.

Some say Canada should be doing more. Some say we shouldn’t be there at all. But unlike some previous deployments, Canada’s response in Mali is measured and expectations appear to be contained.

Take, for example, Afghanistan. A recent New York Times study revealed that the Taliban control or contest 61 per cent of Afghan districts—largely, the numbers suggest, because opposing government forces are much smaller and weaker than previously believed. The newspaper characterizes the outlook as “grim.”

This despite the fact that Canadian soldiers and aircrew spent 13 years fighting insurgents, mentoring Afghan troops and dying alongside their coalition brethren as they tried to drive the Taliban out of the country where the 9/11 hijackers trained.

Afghanistan’s infant mortality, maternal death rates and life expectancy remain among the world’s worst—outreach programs, health campaigns and infrastructure development notwithstanding.

It’s disconcerting, but not unique to Afghanistan. Similar scenarios have played out before in countries where western nations have gone with high expectations to intervene and engineer change, only to find public opinion and political will at home ultimately withers before the job is done.

Thirteen years is a long time to fight a war. American troops are still dying in Afghanistan. Lasting change, however, requires generational commitments—more than can be reasonably expected, many argue.

Canada’s time in Afghanistan was not without its enduring triumphs, however. Small though they may seem in the bigger picture, they are anything but to those who benefited by them. Just ask Djamshid Popal.

Popal was a sickly nine-year-old boy when Captain Americo Rodrigues, a Canadian army doctor from Toronto, discovered him in May 2004 during a daylong clinic in an isolated mountain village, three hours’ drive northeast of Kabul.

He had a heart defect, and Rodrigues said at the time that, without treatment, the frail boy would be dead inside of three months. His heart and liver were enlarged, signs that his condition was in its final, and fatal, stages. Rodrigues feared the boy was already so damaged that even medical intervention wouldn’t save him.

Nine-year-old Djamshid Djan grimaces with pain from his swollen liver during ultrasound tests at the German field hospital in Kabul, Afghanistan, on Thursday, June 17, 2004. [CP PHOTO / Stephen Thorne]

The tools and expertise to repair Djamshid’s malfunctioning heart, however, did not exist in Afghanistan, nor in neighbouring Pakistan.

Enter Saddique Khan of Hamilton, Ont. After reading of Djamshid’s plight, Khan, then a Canadian citizen of just three years, put up some of his own money and, in the years before crowdfunding campaigns eased the process of raising money for such causes, he spearheaded a fundraising drive aimed at bringing the boy to Canada for the lifesaving surgery he needed. It worked. Some $40,000 was raised.

Shafiullah Djan Popal prays next to his dying son Djamshid on a sheet at the Canadian army field hospital in Kabul, Afghanistan, on Wednesday, June 30, 2004. [CP PHOTO / Stephen Thorne]

It was up to Canada.

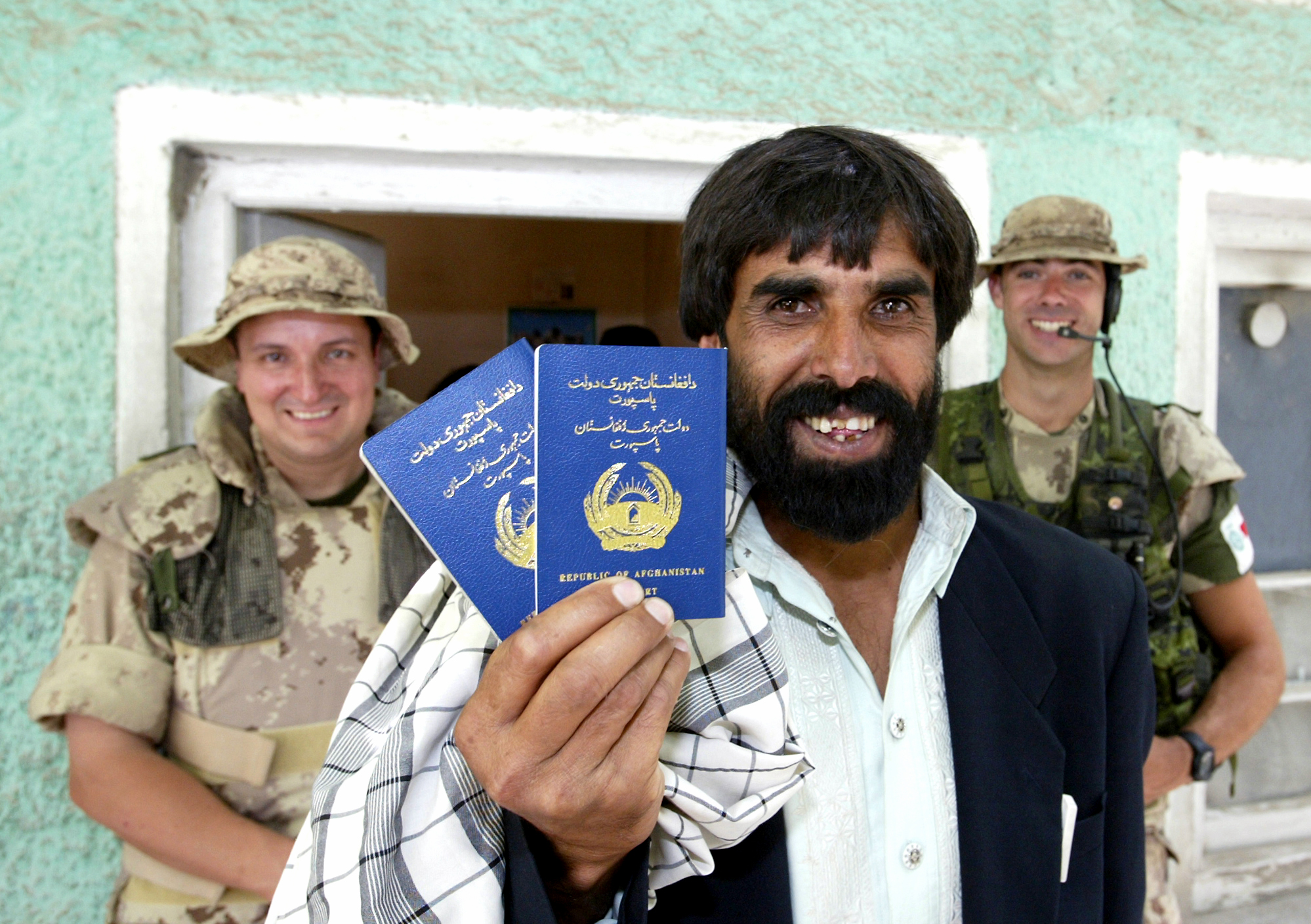

Rodrigues and his team of medics and nurses brought Popal to Kabul. A mountain of bureaucracy was overcome and passports were issued in record time.

Popal’s condition was stabilized at an ill-equipped local hospital, where doctors dispatched Shafiullah to scour the city on foot for a 20-cent ampoule of a common medication.

Popal’s father was overwhelmed as they departed Kabul, believing for the first time that his son who had been slowly dying for three years would get a second chance at life.

Shafiullah Djan Popal holds new passports for himself and his son Djamshid at the passport office in Kabul, Afghanistan. He is flanked by Capt. Americo Rodrigues (left), a Canadian military doctor, and Cpl. Kevin Comeau, the medic who accompanied the father and son to Ottawa. [CP PHOTO / Stephen Thorne]

“I can’t imagine how happy I’ll be hearing his words, saying: ‘Mom, I’m very hungry; I need to eat something.’ Oh Allah almighty, save my child, my sweetheart, my echo, my soul, my shadow.

“May Allah bless all the Canadian doctors and their families, especially their children.”

Corporal Kevin Comeau, a medic from Tabusintac, N.B., accompanied the boy and his father to Canada on Canada Day 2004. They had a stopover in Islamabad, where Shafiullah took the first shower of his life. It lasted hours.

Popal was diagnosed at Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario in Ottawa, where doctors determined that three of his four heart valves had been damaged by a severe bout of rheumatic fever—an ailment that could have been eradicated with antibiotics readily available almost anywhere else. The boy was transferred to Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children, where surgeons repaired his heart.

He was given a supply of medication and eventually sent home.

Over the intervening years, I often wondered how he was doing. I had heard rumours he wasn’t well, that he didn’t have access to the medication he needed. At one point, I even heard he was dead.

Journalist Stephen J. Thorne (left) and Capt. Americo Rodrigues with Djamshid Djan Popal before he left Afghanistan for his life-saving surgery.

Then 10 years later, in 2014, Terry Pedwell, a former colleague of mine at The Canadian Press, tracked Popal down. Through the fixer we had both employed during our time in Kabul, Terry spoke by phone to Popal, who was both grateful to those who had saved his life and regretful he hadn’t stayed in Canada.

Looking back, Popal said he believed life would have been better had he remained here. He was still nurturing a longtime dream of becoming a doctor.

“I was only nine years old, had a big surgery done, and I missed my mom so much and wanted to meet her,” Popal told Pedwell. “But I really didn’t know that if I had chosen to stay in Canada, my mom could have also visited me.”

He was breathing better but his movements were laboured, and he was plagued by nosebleeds brought on by the blood-thinning warfarin he was taking to stay alive.

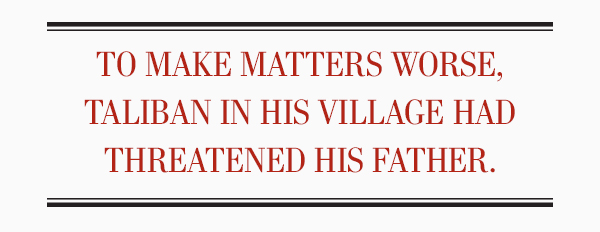

He had suffered a stroke in 2008 and never fully recovered. To make matters worse, Taliban in his village had threatened his father.

“They think we are spies of the Canadian government,” Popal said. “If I knew this would be my situation, I would never come back to Afghanistan again and would stay (in Canada) to continue my studies.”

School was a two-hour walk away, up and down hills. His nose would bleed and he would grow tired. He wasn’t attending regularly. Yet he still spoke of Canada and those who helped him with gratitude and affection.

“I remember almost everything because I have been telling my stories to my friends almost every month.”

Recently, I spoke with our former fixer, who used his savings to earn a medical degree. He was in regular contact with Popal, now 24, ensuring he got his medicine and taking him on regular visits to a cardiologist.

His home village, said my fixer, is “dangerous and not a good place for him to live.” Besides the isolation and the Taliban threats, the area is heavily mined.

Nevertheless, Popal is doing relatively well, he said.

Two Afghanistan tours and 14 years later, Americo Rodrigues recalls now what he describes as “a very moving experience” encountering Djamshid.

“He was nine but he looked six,” said Rodrigues, who retired a major in 2016 after 15 years and now provides civilian contract medical services to the military. “He had a wonderful smile; I still remember that to this day.

“It wasn’t myself who saved him, it was ‘we.’ We were all there. It was an example to me of how kind and compassionate and generous Canadian citizens are.”

His own experience in Afghanistan, he said, reminded him how fortunate we are to live in Canada. In subsequent tours, he saw “vast improvements” in living conditions and the foreign-aid system in Afghanistan, including better assistance for children and co-operative programs with Pakistan that allowed transfers of more serious medical cases across the border.

“That was personally satisfying.”

Advertisement