The fact is that medical researchers from all over the world who have no stake in global politics—including the World Health Organization— say it’s neither. They say they have traced COVID-19 to a wet market in Wuhan and it likely came from a bat. It’s as simple as that.

Nevertheless, the rumours and the actual source of the virus has been exploited by racists, nativists and xenophobes intent on driving a wedge between ethnic groups.

“Such rumours may have even jeopardized the working relationship between Western scientists and their Chinese counterparts searching for a COVID-19 vaccine,” wrote sociologists S. Harris Ali and Fuyuki Kurasawa of Toronto’s York University in The Conversation.

In times of crisis, rumours spread like a virus itself—partly out of fear, partly by malicious intent, and partly because people tend to want to believe that complex problems can be solved by simple solutions, such as some of the purported “cures” advanced by non-medical pundits and self-appointed experts.

“When we are dealing with a situation of such importance and we don’t have as much information as we would like, rumor serves as an outlet for our anxiety and a method of filling gaps in our knowledge,” Cathy Faye wrote in Behavioral Scientist on April 6.

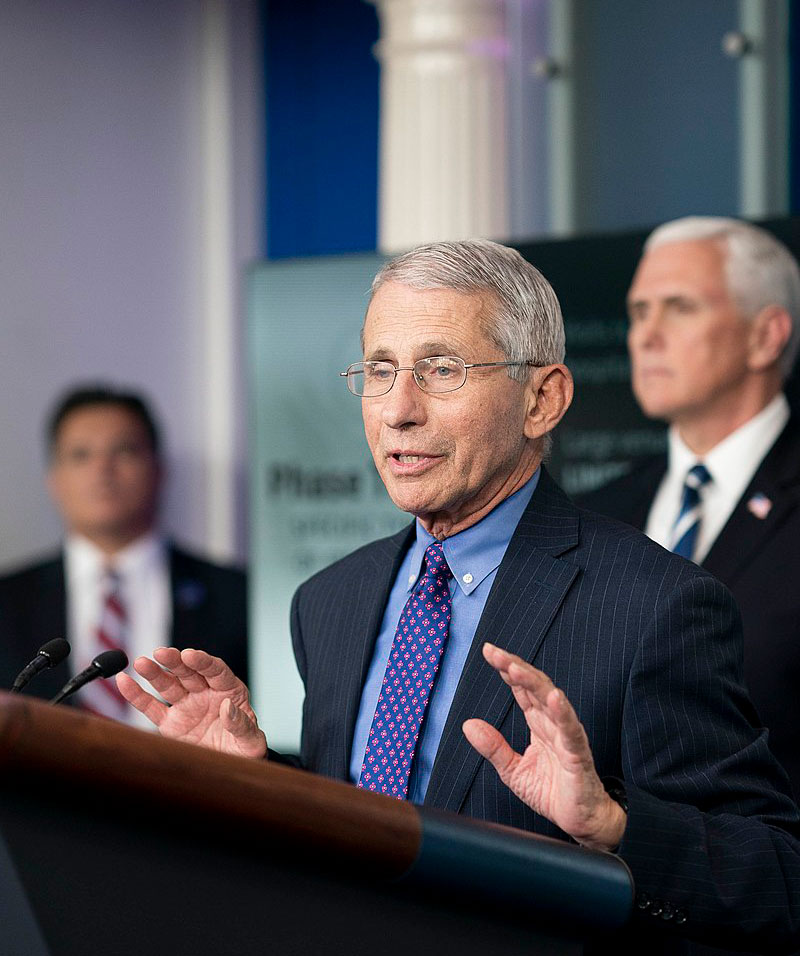

Public officials are cautious about making premature pronouncements in the early stages of complex emergencies, wrote Ali and Kurasawa on March 22. Instead, they carefully craft statements “to ensure accuracy and avoid the pitfalls of misinterpretation and exaggeration.”

“Somewhat paradoxically, this careful approach may also contribute to the formation of an information vacuum that rumours and falsehoods are all too ready to fill.” In the digital age, they wrote, the time needed to analyze, assess and communicate accurate information cannot compete with the instantaneous spread of misinformation on social media platforms.

It’s a heyday for those who would seek to destabilize and gain advantage. And the phenomenon is far from new or unique to the coronavirus. It can affect entire countries, small enterprises or mere individuals—or all of them at once.

Rumours about the source and nature of an accelerating Ebola epidemic were rampant during December 2018 elections in the Democratic Republic of Congo after the ruling government cancelled voting in affected areas, effectively eliminating as many as two million opposition ballots. As a result, disenfranchised voters ransacked treatment centres and obstructed community health programs.

In a January 2019 editorial, the medical journal The Lancet declared that “from its very start, the people of DR Congo have perceived the Ebola response as politicised.”

In the face of widespread violence, poverty and hunger, many Congolese considered the Ebola virus outbreak “a comparatively minor threat” and the scale of the international response as disproportionate and suspiciously timed in the lead-up to the first democratic presidential election in decades. Rumours flourished.

“A substantial proportion of the Ebola responders’ work had to be directed towards dissipating these concerns and building trust with community leaders,” the journal said.

“It is therefore a pity that their fears, at least in part, were proven to be justified.”

Analysts told The Lancet that concerns that led to shutting down voting in key areas “were probably not legitimate reasons to postpone the elections,” noting such measures were not used, for instance, to limit gatherings in churches and schools.

It called the consequences of the decision on the Ebola response “immeasurable, not only for its effect on epidemic control but also in terms of trust lost.”

“These elections were celebrated as an important step towards a more democratic process and populous sovereignty. That this was jeopardised by leveraging the very health concerns that the Congolese people need the Government to alleviate is deeply regrettable.”

On a smaller scale, in February, a 36-character WeChat message brought down the Grand Crystal Seafood Restaurant in Burnaby, B.C., in less than a day. The message falsely claimed that the restaurant had been shut down for 14 days after an employee contracted COVID-19. Neither claim was true, but they went viral and the restaurant suffered an immediate 80 per cent drop in business.

A recent poll by the U.S.-based Pew Research Center suggested that 48 per cent of Americans have heard false information about COVID-19, and many believed it. The same poll indicated that 23 per cent of Americans believed that the virus was purposefully manufactured in a laboratory.

“Concerns about deliberate disinformation campaigns as the source of some COVID-19 rumors have also begun to surface,” wrote Faye.

“Specifically, there is evidence that both China and Russia have waged disinformation campaigns pointing to the United States as the origin of the virus, with the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs endorsing the theory that it was brought to Wuhan by the U.S. Army. “

The issue has become of such a concern that government agencies in Canada, the United States and elsewhere have developed websites and units devoted to rumour control.

The U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency recently set up a “Coronavirus Rumor Control” web page (www.fema.gov/coronavirus/rumor-control) to “help the public distinguish between rumors and facts.” The site presents a series of myths with corresponding facts that dispute them and points readers to trusted sources for more information.

The Centers for Disease Control, the World Health Organization, the U.S. Department of Defense, and several news outlets have established similar pages, all devoted to quelling the spread of rumour.

“When faced with uncertainty and unpredictability, communicating early during a crisis can be critical to building essential trust,” said a Government of Canada site (https://guides.co/g/community-based-measures-to-mitigate-the-spread-of-coronavirus-disease-covid-19-in-canada/174229). “Misinformation that is spread through social media is a significant concern.

“Building trust in institutions and spokespersons in advance of a pandemic can mitigate the potential risks of misinformation, along with creating a clear focal point for accessing information.”

The science and study of rumours came to the fore during the Second World War, when reliable information was hard to come by and people were uncertain what the war would mean for them, when it would end, or how devastating it might be.

“They sought information that was often simply not available or, because of wartime censorship, not provided,” Faye wrote. “They were anxious and uncertain and wary of the information they were receiving from the government and the news.”

With Cold War advances in transportation and communication, information travelled farther and faster, and the rumour mill reached unprecedented levels.

When they weren’t escalating the nuclear threat posed by silos of intercontinental ballistic missiles and proxy wars fought in the Koreas, Vietnam, Cuba and elsewhere, the superpowers brought the Cold War to doorsteps on both sides of the Iron Curtain, almost all without the aid of the Internet. In those days, rumours spread primarily by documents and word of mouth.

Largely as a result, an entire generation was raised on fear—fear of the “red menace;” fears there were spies in our midst; fear of nuclear annihilation.

Cold War rumours were often planted by one side or another, designed to destabilize one society or the other, and undermine or shore up public support for one cause or the other.

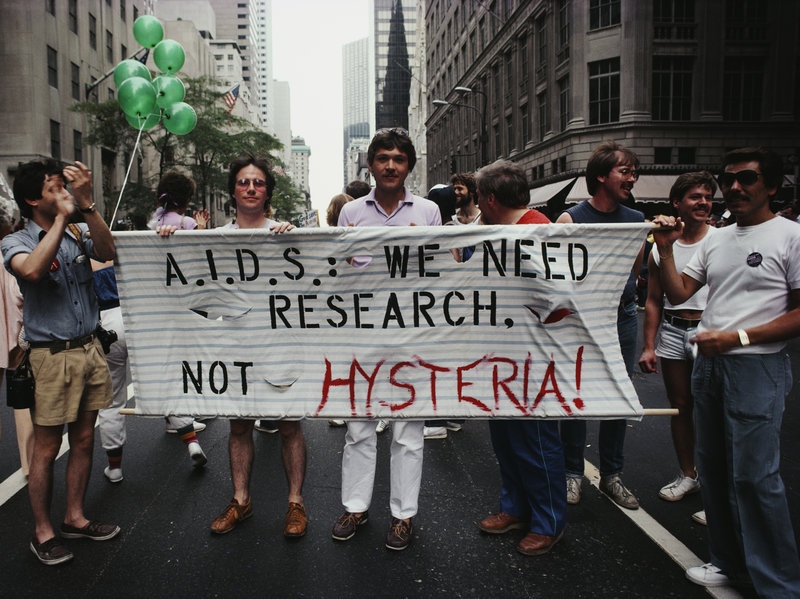

There was a rumour in the early 1980s that Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) was the product of secret U.S. military research at the Fort Detrick Laboratory in Maryland.

The rumour was the product of a KGB (Soviet intelligence service) disinformation campaign.

“The AIDS disinformation campaign was one of the most notorious and one of the most successful Soviet disinformation campaigns during the Cold War,” Thomas Boghardt, a historian at the U.S. Army Center of Military History, told the BBC in 2017. Boghardt studied the case in detail.

Agents first planted the story in a small, KGB-funded journal in India on July 17, 1983. It asserted that AIDS was the product of U.S. experiments and it might invade India. It had an anonymous American scientist linking it to Fort Detrick.

There wasn’t much interest, at first. Two years later, however, Soviet news outlets ran the story, craftily citing the Indian reports. The tale then spread rapidly and persisted for years. It can still be found on conspiracy sites on the fringes of the Internet.

KGB field officers spent up to a quarter of their time on what were called “active measures.”

Boghardt believes the KGB station in New York came up with the AIDS idea. It was intended to help foster distrust in American institutions and rumours of covert biological warfare programmes.

“Intelligence meant not only gathering but using—or weaponizing—that intelligence to influence operations,” he explained.

Such active measures help sow confusion and distrust, either among countrymen or between allies. In 1980, the Soviets spent US$3 billion (more than $10 billion in 2020 dollars) on such activities, and it was far from the first time it employed such tactics.

During the 1980s, the United States tried to counter the tide of KGB disinformation by setting up the Active Measures Working Group, comprising experts from various government agencies.

“The only way you could counter active measures was by coming back with the truth,” explained David Major, a former FBI official who served on the group.

It would identify fake stories and then advise the media about their source, confirming it as what has today come to be known as fake news. One claimed Americans were visiting South America to harvest body parts under the guise of adopting children.

The BBC reported that the KGB placed emphasis on not just recruiting people who had access to secrets but people who could influence opinion—so-called “agents of influence.”

“The Soviet and Soviet Bloc intelligence agencies were very good at cultivating contacts with journalists for instance, or intellectuals, who sometimes knowingly and sometimes unknowingly would be used as launching platforms for fake or leaked stories,” said Thomas Rid of King’s College, London.

The practices have not stopped.

“The Soviet Union may have dissolved in 1990-91 but Soviet intelligence stayed virtually intact both in terms of its organization and the goals it pursued—and that includes active measures,” said Boghardt.

Given that it is human nature to latch on to ideas and stories that reinforce individuals’ own beliefs, it’s an ideal environment in which to easily manipulate large numbers of people.

Gaslighting—the practice of undermining widely accepted facts and creating doubt with a constant flow of disinformation—has become commonplace.

ISIS, al-Qaida, Syria, North Korea and other groups and states have used websites and social media to foster fear and spread rumour and disinformation. The methods may be new, but not the art.

Russian bots, hackers and trolls helped turn the tide of the 2016 U.S. election by fostering division, hacking the Democratic National Committee and spreading fake news.

The United States is not the only victim. From a nondescript business centre in the Russian city of Saint Petersburg, known as the troll factory, n’er-do-wells have been infamously attempting to manipulate public opinion and election campaigns throughout Europe and elsewhere—including Canada, although there is no publicized evidence their efforts had any effect here.

Canadian troops leading a NATO mission in Latvia have been in constant cyberwar with Russians who have been spreading false information in the Baltic state since word came down that the mission would be launched in 2016. Their platforms: fake-news websites, automated Twitter accounts and other social media.

The Russians want to turn Latvians against the NATO force ensconced outside Riga. Similar campaigns are underway throughout the handful of Baltic states where NATO has installed forces to discourage Russian aggression.

ScienceAlert.com has warned that fake accounts—common on social platforms including Twitter, Facebook and Instagram—are now spreading coronavirus-related fear and fake news. The site warns “the exact scale of misinformation is difficult to measure.”

Writer Peter Suciu reported in Forbes on April 8 that some of these fake accounts closely resemble legitimate accounts from trusted sources.

“But that is only part of the problem,” wrote Suciu. “In many cases, bots are responding to actual legitimate accounts as a way to discredit them. In other words, it isn’t just misinformation but fake accounts that are making actual commentary seem illegitimate!”

ScienceAlert noted that bots are often easy to spot. They typically have no last names and instead have long alphanumeric handles; they have posted or tweeted just a few times, have only recently joined the social media site, have no followers and their posts all share a common theme of spreading alarmist comments. They tend to follow influential news sites and government authorities.

“What the endgame is for this remains unclear,” Forbes reported, “but the sad truth is that it helps blur fact from misinformation.”

The problem is exacerbated by people sharing via retweets, reposts and even simply by “liking” tips and stories they think are useful.

“If only one news outlet is reporting something that seems like huge news—that should be a red flag,” Suciu wrote. “Likewise, if a post on social media references the World Health Organization, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or similar respected authority, yet their respective website doesn’t have that information front and center, it should be questioned.”

Advertisement