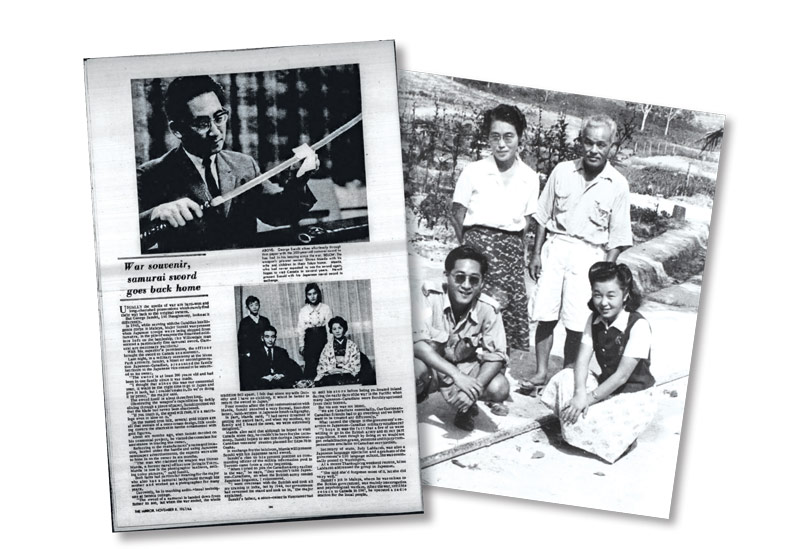

WW II Japanese-Canadian veteran George Suzuki returns his Samurai sword war trophy to Japanese Vice-Consul Tamotsu Furuta in 1967. [Doug Griffin/Toronto Star Photograph Archive/Toronto Public Library]

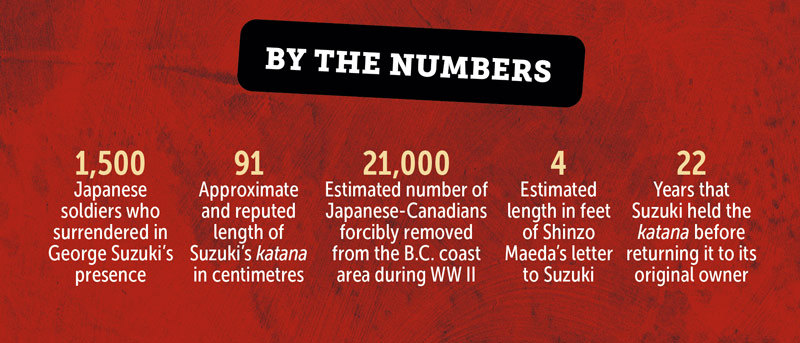

George Suzuki watched as 1,500 Japanese soldiers surrendered their arms.

Though VJ-Day had come and gone, a new conflict—the Indonesian National Revolution—was already taking hold in Sumatra. There, British forces, under whose authority the Canadian Suzuki served within intelligence, scrambled to evacuate old enemies—and their weapons sought by anti-colonial nationalists.

Clambering aboard Royal Navy vessels, defeated Japanese troops stacked rifles and ceded swords, leaving them in piles. It was then that one blade, a katana traditionally wielded by samurai warriors, caught Suzuki’s eye.

The reputably two-century-old antique, said to measure “about three feet long” (91 centimetres) in a North York Mirror article, boasted an elaborate sharkskin hilt “ornamented with gold figures” and adorned with silk cording.

It was, thought Suzuki—a self-identified Nisei (or a second-generation Japanese-Canadian)—an object of great beauty, indeed a worthy souvenir to take home.

The army translator and broadcaster received permission to claim it as his own.

Coverage of the event in a Toronto-area newspaper. During the war, Suzuki meets with fellow Japanese-Canadians who had fled to Singapore.[North York Mirror/newspapers.com; CWM/19830626-001 ]

During the subsequent years, Suzuki had ample time to reflect on the twists and turns his personal war had taken: Being forcibly uprooted from the B.C. coastal area with some 21,000 Japanese-Canadian civilians after the Dec. 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor attack; being one of approximately 4,000 such citizens sent to work on sugar beet farms, crowded into shacks and other farm buildings under dreadful conditions; and first being denied military service until late in the war, when a British captain recruited and deployed him within South East Asia Command.

The sword of a samurai is handed down from father to son, but when the war ended, the whole tradition fell apart. I felt it would be better to return the sword.

By 1967, however, Suzuki’s continued possession of the katana war prize had left him questioning whether it should remain so.

“The sword of a samurai is handed down from father to son,” he remarked in a newspaper interview, “but when the war ended, the whole tradition fell apart. I felt that since my wife Dorothy and I have no children, it would be better to return the sword to Japan.”

In honour of Canada’s centennial year, he resolved himself to track down its original owner.

Suzuki visited the Japanese consulate in Toronto, referring to the manufacturer name and location reportedly buried under the blade’s hilt to begin the search. Aided by expert investigations and Japanese newspaper advertisements, the Canadian veteran had his answer within six months: the katana once belonged to Shinzo Maeda of Tokyo, a former naval officer-turned-business entrepreneur.

A four-foot (122-centimetre) letter, written in formal Japanese brush calligraphy, unfurled in Suzuki’s hands about four months later. In the missive, Maeda acknowledged that “I had never dreamed of getting my sword back.”

Despite neither sender nor receiver having the means to visit the other, with the katana’s handover due to occur by proxy, its once-and-future holder remained “extremely delighted.”

And, so it was, after maintaining the family heirloom for some 22 years, Suzuki finally relinquished it to Japanese Vice-Consul Tamotsu Furuta at a late-1967 ceremony, replaced by Maeda’s naval sword as a parting gesture of goodwill.

Once enemies, now friends, both had thus fulfilled a journey of reconciliation while, from Toronto to Tokyo, the katana embarked on its own journey home.

Advertisement