Wartime restrictions accidentally created a golden age for Canadian comic book heroes with patriotic messages

Johnny Canuck debuted in the February 1942 issue of Dime Comics. [LAC/2266472;LAC/c-137065]

Torontonian Leo Bachle was just 16 in 1941 when he created Canadian wartime comic book superhero Johnny Canuck.

“I didn’t see it as propaganda at the time,” he said in a CBC interview in 1995. “I created Johnny to give Canada a hero. I really believed in the war effort. I felt very nationalistic.”

Leo Bachle, creator of the Johnny Canuck comic book series. [Rachel Richey]

With typical Canadian reserve, these heroes didn’t always possess Superman-like powers.

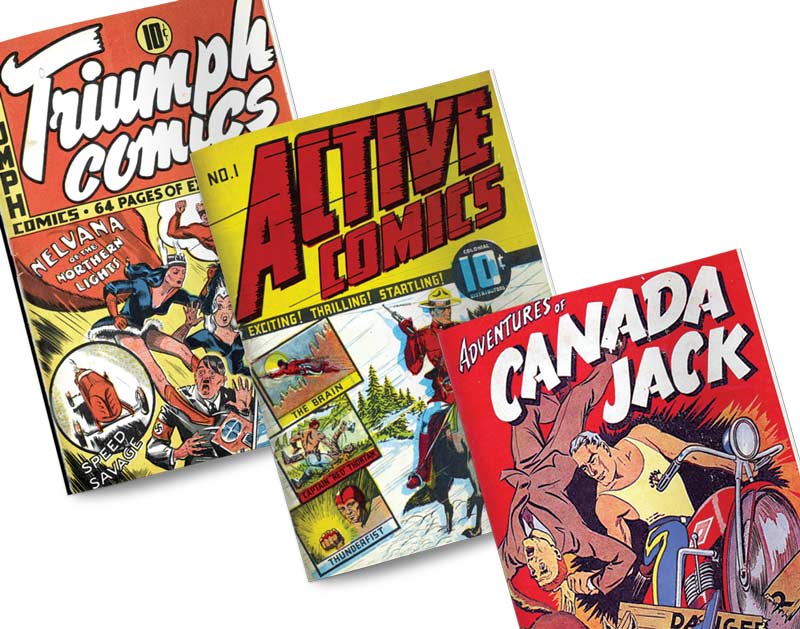

Bachle was in the right place at the right time with the right talent. Canada’s War Exchange Conservation Act of December 1940 banning non-essential imports had an unintended benefit to the war effort. Among paper products it barred were pulp magazines and comic books. In blocking popular American superheroes from comics-starved kids—and many grown-ups—it opened a patriotic door and a number of Canadian comic book publishers stepped in to fill the void. A lineup of superhero comics was born, known as the Canadian Whites because between their coloured cover pages were black-and-white comics.

One issue paired Robin Hood (“Hero of Olden Times”) with Kip Keene of the RCMP (“Star Rookie of Men of the Mounted”). [comicbookdaily.com]

One of the first out of the gate was publisher Cyril (Cy) Bell who stepped up with his Wow Comics: made in Canada, by Canadians, for Canadians, and about Canadian wartime superheroes. And, with typical Canadian reserve, these heroes didn’t always possess Superman-like powers.

“He was brave, he was smart, but a superhero who takes on Hitler,” said Bachle (who later went by the name Les Barker) of his immensely popular comic character Johnny Canuck, who debuted in the February 1942 issue of Bell’s Dime Comics.

Bell was just one of several publishers who leapt at the opportunity. Within three months of the act’s passage, Anglo-American Publications of Toronto and Maple Leaf Publications of Vancouver jumped in with the first issues of Robin Hood Comics and Better Comics, respectively. Also in Toronto, Adrian Dingle and twins Rene and Andre Kulbach launched the first issue of Triumph-Adventure Comics six months later. Then came Bell with his existing company Commercial Signs of Canada. Educational Projects threw its hat in the ring just over a year later in Montreal.

“All the stories were Canadian—the writing, the artwork, everything.”

The entrepreneurial Bell enjoyed immediate success. By Wow Comics No. 5 (February 1942), he reckoned it was time to expand beyond a single title and debuted Active Comics and Dime Comics that same month. Active Comics No. 1 introduced hero Corporal Wayne Dixon of the RCMP.

Made-in-Canada issues included Triumph Comics, Active Comics and Adventures of Canada Jack. [comicbookdaily.com]

Bell kept up the pace. When Triumph-Adventure Comics’ third issue flopped, Bell took over the company and hired its co-creator Adrian Dingle as his art director. To reflect his rapidly growing new direction, Bell renamed his company Bell Feature Publications in May 1942.

“We were strictly Canadian,” said Bell proudly in an earlier CBC program entitled “Superheroes to Call our Own,” which aired on Oct. 5, 1971. “All the stories were Canadian—the writing, the artwork, everything.”

Indeed, they were an enthusiastic bunch; infused with and driven by an infectious sense of wartime patriotism.

“Every Friday when the boys got their cheques, we’d get together at the old Piccadilly Hotel,” said Bell. “That’s where a lot of the stories were hashed over.”

“We lived in sort of a world of fantasy,” added Dingle in the same broadcast. “We had rather grandiose illusions—solid gold Cadillacs, exorbitant salaries and everything. We were thinking up great ideas, and Cy was always part of it. He was a very dynamic character. And our artists were very diverse. One was Leo Bachle. He was interesting. His thoughts went from the macabre to the strongest form of humour.”

Bachle was, in fact, one of Bell’s star artists. Expelled from high school at 15, he ran away from home and joined the army. Underage, “they kicked me out,” he said. Working at a local delivery job in Toronto for $10 a week he encountered Bell, who recognized his talent and immediately hired him at $25 a week.

In the 1995 interview, Bachle explained his Johnny Canuck creation to the CBC. “I patterned him on what I thought I’d like to be,” he said. “Johnny was all over. He got shot down in Libya where he discovers this metal, ‛uranium.’ He meets Hitler and punches him in the face. You couldn’t kill Johnny.” To stay relevant, Bachle followed the war closely—most of Johnny’s episodes related to actual battles and locations.

The creators weren’t all men. Bell’s pool of freelancers included artist Doris Slater and writer Patricia Joudrey, two of the few women involved in Canadian wartime comics.

Nor were all the superheroes men. Nelvana of the Northern Lights was generally considered by comic book historians as Canada’s first distinctly female superhero (beating America’s Wonder Woman by three months). Created by Adrian Dingle and inspired by his friend, Group of Seven affiliate artist Franz Johnston’s recounting of a legend following an Arctic trip, Nelvana first appeared in the August 1941 issue of Triumph-Adventure Comics before it and Dingle became part of Bell’s publishing group. Nelvana was based on a mythical Inuit figure of the same name, but Dingle changed her a bit.

Half-Inuit demi-goddess Nelvana of the Northern Lights was the first major female superhero in the comics, predating America’s Wonder Woman by three months. [LAC/e011166649]

“I did what I could with long hair and miniskirts and bringing her into the war effort. Of course, everything had to be patriotic,” he said.

Unlike Johnny, Nelvana did possess supernatural powers. She could fly at the speed of light along a giant ray of aurora borealis and had super powers—including her mythical father Koliak’s powerful ray that melted metal and zapped out radio communications—plus she could make herself invisible.

Like Johnny Canuck, Nelvana was a Nazi fighter. In her first escapade, she thwarts an Arctic invasion by Nazi-allied warriors who are armed with special rays. In another, she fights Nazis as they infiltrate Ontario to try to steal a new Allied weapon called the ice-beam.

Not all the heroes were fighting for Canada in particular. Another of Dingle’s creations before he joined Bell was a character named Spanner Preston. He was Canadian but serving in the Royal Air Force.

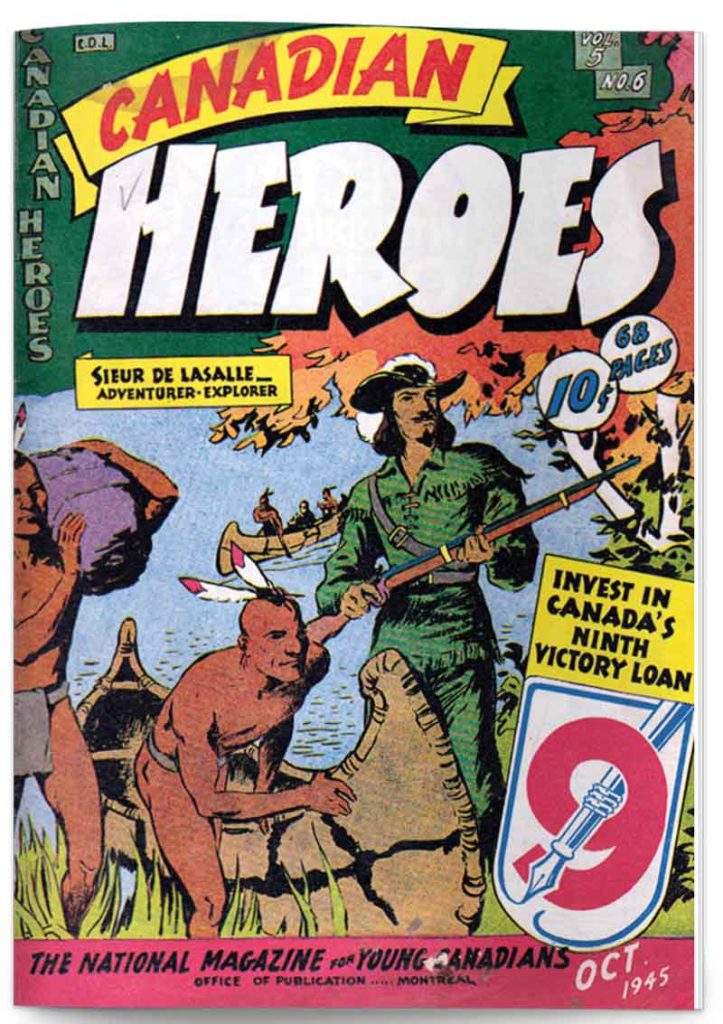

Educational Projects of Montreal started out in 1942 with Canadian Heroes, which had a less supernatural or mythical bent. Artist Fred Kelly originally focused on a series that included prime ministers, governors general and Mounties. But demand by kids soon forced a shift to fictional heroes and Canada Jack was launched, the brainchild of artist George M. Rae.

To boost kid appeal, this creation had a clever twist. The Canada Jack Club, a children’s group, helped the hero in battles protecting the home front against Nazi saboteurs and agents trying to undermine Canada’s war effort. To the delight of younger readers, it was a real club they could join. In each issue, Rae provided club news on coming issues, such as “So-o-o. We’re going to have another adventure and we’ll have a job for you members…looks exciting too! A THRILLING ADVENTURE in the NEXT ISSUE!!!”

Another kids’ club through comics more directly helped the war effort in 1942. A centrespread in Active Comics invited followers to join the Active Club. Its motto was ‘Strength and Fair Play’ in school, sports, work and play. A new character, the agile and clean-cut Active Jim, led the club while starring regularly on the comic’s pages. He’s well-informed too: telling readers about major war developments, such as the raid on Dieppe and the Churchill-Roosevelt Casablanca summit.

The Active Club was exciting for boys and girls, offering contests and wartime conservation and safety tips. Each issue listed new club members and their cities and towns across Canada. They formed local branches, built clubhouses, held fundraisers and war bond drives, and watched out for potential undercover operators or saboteurs in their hometowns. It made them feel like part of the war effort.

Some pages featured readers who joined the Active Club, which held fundraisers and war bond drives. [LAC/e011166502]

Artist Gerald Lazare also made his debut as a teenager. At just 15, he sent some samples of his work to Bell Features hoping for advice on how he could improve it. Bell called right back and asked if he was ready to start.

In Dime Comics April 1944, Lazare introduced his first new superhero, Nitro, who lacked super powers but solved crimes using his superior strength, athletic prowess and intelligence. The next issue starred Lazare’s second creation, Drummy Young, a dance band leader and drummer and a super-smart crime solver.

Crime-fighter Nitro made his debut in the April 1944 edition of Dime Comics. He had strength, athletic prowess and intelligence, but no super powers. [LAC/e011166589]

Lazare didn’t stop there. One more short-lived series featured Tommy Tweed. This teenage super hero first showed up in Commando Comics September 1945. Tommy ran away from home with his buddy Suds Bramblebush. It was at the war’s end and their first escapade fit with the time: battling a bunch of German prisoners of war who escaped from Canadian camps and planned to re-establish the Nazi regime starting on Canadian soil.

All the heroes weren’t entirely fictional. A comic book biography of Canadian Aviation Hall of Famer Elsie MacGill appeared in an issue of True Comics in 1942, using her nickname, “Queen of the Hurricanes.”

There were many other heroes created: Speed Savage, Captain Wonder, Private Stuff, The Brain, The Invisible Commando, Chip Piper, Southpaw, Super Sub, and RCAF pilots Jimmy Clarkson, Lee Pierce and Ace Bradley. Dozens in all.

The October 1945 issue of Canadian Heroes was 68 pages with a cover featuring adventurer and explorer Sieur de La Salle. It was 10 cents. The year also saw two latecomers anxious to get in on the action: Al Rucker Publications and Superior Publishers. But the Allies were victorious in Europe and American comics would soon be back on the shelves.

Canadian Heroes featured explorer Sieur de La Salle on the October 1945 cover. It was 10 cents. [comicbookdaily.com]

Johnny Canuck and Nelvana of the Northern Lights have become icons.

In the fall of that year, Educational Projects folded. Maple Leaf Publications attempted to survive by printing in colour and exporting to the United Kingdom but they, too, soon had to close shop. Industry leader Bell, who in a five-year span had employed over 60 artists, diversified and took aim at the U.S. and U.K. markets with two new series—Dizzy Dan Comics and Slam-Bang—but Ottawa’s limits on newsprint soon ended that initiative. By the end of 1946, the great Canadian wartime comic book run had ended.

The Canadian books had been instant hits and sales figures were through the roof for the entire war. They appealed to the nation’s patriotism and undoubtedly boosted recruiting and morale. And, importantly, they got kids and teens behind the war effort.

A few of the superheroes live on. Johnny Canuck and Nelvana of the Northern Lights have become icons of the era’s comics and part of Canada’s cultural heritage. They were commemorated in a special issue of Canada Post stamps in 1995.

Issued in 1995, a 45-cent stamp paid tribute to Johnny Canuck. Artist Leo Bachle was just 16 when he created the Canadian superhero. He later changed his name to Les Barker and became a comedian. [LAC/2266472]

Advertisement