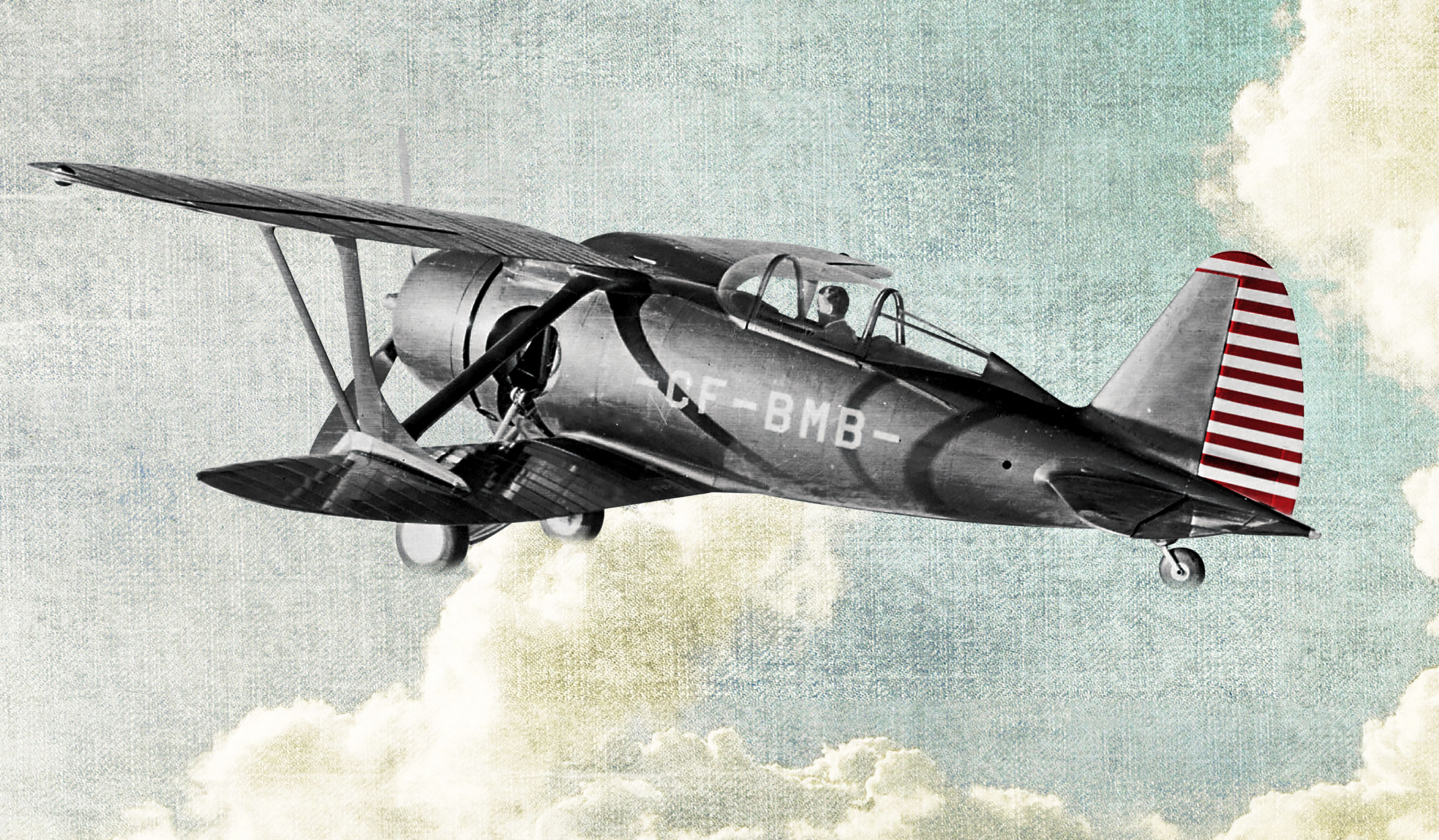

FDB-1. [Alamy]

It was 1939 and the Canadian Car and Foundry Company’s (Can-Car) new FDB-1 fighter-bomber had just demonstrated that it could out-climb a Hurricane or Spitfire.

After flying it, an RCAF test pilot extolled its dogfighting agilities, which he said would also challenge that of contemporary fighters. Aeronautical engineer Michael Gregor had earlier convinced Can-Car’s Montreal headquarters to hire him to design and build a new highly manoeuvrable fighter-bomber at their facility in Fort William, Ont. (now part of Thunder Bay).

Gregor’s creation was somewhat radical: a biplane at a time when monoplanes were all the rage. But Gregor was a huge fan of biplanes and of enhancing their potential. “They’ll start the war with monoplanes but finish it with biplanes,” he said. Can-Car’s general manager Leonard Peto was evidently impressed, thinking “it would find a heavy market in Britain and France.”

Can-Car was founded in 1909 and built railway cars and the occasional minesweeper before falling on hard times in the 1920s. A 1935 tax deal with Fort William city council aimed at boosting the area’s Depression-era economics prompted a resurrection—this time to build airplanes.

They were soon off to the races building Grumman G23 biplane fighters, the majority of which went to Spanish Nationalist Forces and the Royal Canadian Air Force, which rechristened them the Goblin. Over the years, Can-Car also manufactured Hawker Hurricane fighters, Curtiss Helldiver bombers, North American Harvard trainers and others.

All these aircraft were built under licence from original designers. In 1937, Can-Car was longing for the distinction and prestige of having its very own design, development and engineering capability and of establishing itself as a world leader. With war clouds on the European horizon, a cutting-edge fighter-bomber would be timely—and lucrative RCAF and Allied contracts could be in the offing.

Enter Michael Gregor. The 49-year-old Russian-born engineer, who had changed his last name from Grigorashvili, was fresh from working on a number of unique airplane designs south of the border. At Brunner-Winkle Aircraft Company, he had been instrumental in creating a successful and popular biplane called the Bird, a three-seat taxi and joy-riding aircraft. The Bird had many new and innovative design features that stood out among its peers, like a thick upper wing to enhance lift.

A stint followed as chief engineer at Seversky Aircraft Corporation of Long Island, culminating with his SEV-3 Sport Amphibian design. His own Gregor Aircraft Corporation at Roosevelt Field in New York prototyped his biplane, the GR-1 Sportplane. The man clearly had a passion for biplanes and how to draw out their best.

So when Can-Car hired him as chief aeronautical engineer, it seemed a win-win.

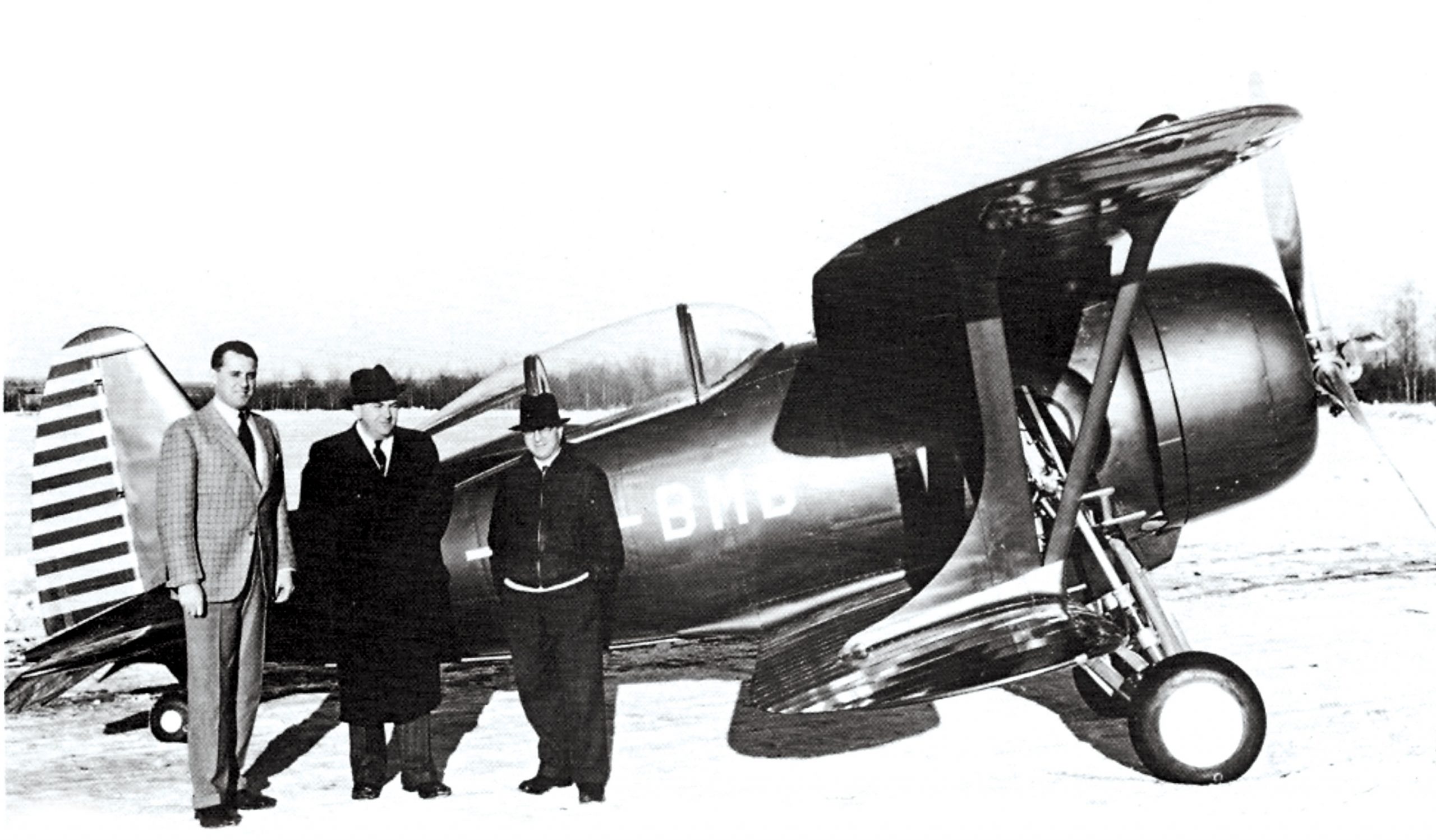

Standing beside the prototype Gregor FDB-1 are (from left) designer Michael Gregor, Can-Car representative David Boyd and test pilot George Ayde. There are questions as to where the FDB-1 (opposite) had its first flight. [Wikimedia]

Gregor’s convincing pitch included marrying some of the latest aircraft technologies—stressed-skin construction, flush riveting, bubble canopies, streamlining, retractable gear—with the proven dogfighting agility of the biplane. He came up with an elegant and pleasing design in the FDB-1.

Its most striking feature was the graceful gull-shaped upper wing—with unusually long automatic slots—designed to enhance the pilot’s forward visibility in flight, gaining him an edge in a dogfight. But as with most aircraft design challenges, that meant a trade-off: the unique wing interfered with visibility during takeoff, landing and taxiing.

The FDB-1’s short stubby fuselage also hindered landing and taxiing visibility. But the trade-off here was worth it. Only 6.6 metres long, it enhanced manoeuvrability—enabling what aircraft designers called “short-coupling” as seen on today’s competitive racing airplanes. That enhanced manoeuvrability gave it a further edge in a dogfight, where it could employ precise tactics over the enemy to train fire with its twin 13-millimetre machine guns. Or a sharp 7-G pull-up after diving to drop its two underwing 53-kilogram bombs.

Although Gregor had wanted a 1,200-horsepower engine, the FDB-1 was powered by a standard 700-horsepower Pratt & Whitney Twin Wasp engine, which boasted a maximum range of just over 1,500 kilometres.

Following model testing in the Hawker Aircraft wind tunnel at Kingston-upon-Thames in England, construction got underway in the spring of 1938. Six months later, resplendent in high-gloss metallic gun-metal grey paint, its Canadian registration CF-BMB in white letters and red-and-white stripes on the rudder, the FDB-1 was rolled out for the first time.

There is some controversy over the date of the prototype’s first flight. According to archival research by historian Jonathan Grenville Kirton, author of the 2009 book Canadian Car and Foundry Aircraft Production at Fort William on the Eve of World War II, published by the Thunder Bay Historical Museum Society, it first took to the air at Saint-Hubert, Que., in April 1939. A 1972 article in Air Pictorial magazine reported the initial flight was on Dec. 17, 1938, with Can-Car test pilot George Ayde at the company’s Fort William airfield.

Either way, the FDB-1 achieved its design philosophy of extreme manoeuvrability and was rated as pleasant to fly. But “lack of visibility, making it difficult to handle during take-off and landing, brought adverse comment,” the magazine reported. “Further criticism was levelled at the control surfaces’ areas, which needed adjustment to prevent over-control [but an advantage in a dogfight], and at the pilot’s canopy, which vibrated badly at high speeds and during loops, making a stronger frame mandatory.” Flight trials continued over the ensuing weeks.

Canada’s Department of Transport (DOT) was evidently impressed. On May 9, 1939, J.A. Wilson, DOT’s controller of civil aviation, wrote a letter to Air Commodore E.W. Stedman, the RCAF’s chief aeronautical engineer, regarding official RCAF flight trials. The letter cited Can-Car’s trials:

“The aircraft has been spun at least twice to complete eight full turns. Also, the tail parachute has been tested in the air for correct functioning and ejection.” The parachute was provided for safety in case of non-recovery from a spin—when deployed it forced a nose-down attitude which restored airflow over the control surfaces, allowing spin recovery. The parachute was then jettisoned.

The letter added that “the terminal velocity dive test was performed from 23,000 feet, attaining an indicated air speed of 472 mph…. All acrobatic manoeuvres can be performed smoothly and satisfactorily at all speeds, with no appreciable vibration in the more violent manoeuvres.”

On the morning after the letter was received by Stedman, an RCAF test pilot, Flight Lieutenant J.E. Wray, discussed the DOT request with his senior, Squadron Leader Allan Ferrier. Wray was sent to Montreal that same afternoon where, after a final go-ahead from a DOT inspector, he strapped in, advanced the throttle and lifted CF-BMB off the runway.

Apart from an alarming canopy vibration during loops, Wray was quickly taken by the aircraft’s snappy handling. Performance, not so much. Can-Car’s report had boasted an optimistic climb rate of 3,400 feet per minute (against the Hurricane’s 2,780), but Wray recorded an initial climb rate of only 2,800. Can-Car had reported a terminal velocity dive speed of 472 miles per hour, but Wray’s trial reached only 402.

The pilot was blinded by the gull-wing while taxiing but “it has manoeuvrability to the extreme,” Wray wrote in his flight test report. “Below 15,000 feet, a contemporary low-wing monoplane or single seater, despite superior performance, could not successfully engage the Gregor singly.”

Impressive, but these numbers and comments came with the aircraft at a lighter weight than it would be when operational with guns, ammunition, armour and bombs. And while handling was superb, performance wasn’t beating current monoplane fighters by much. Perhaps with the proposed 1,200-horsepower engine it could have. But that would mean months of further design and testing, and this was 1939.

Hurricanes and Spitfires were already proven and operational. Those war clouds were now towering and Can-Car’s Hurricane production lines were gearing up. Holding off on those to develop an entirely new line of as yet unsold FDB-1s would seem folly. Without clearly superior performance, the RCAF wasn’t convinced that regression to biplane design was the way forward.

The Gregor FDB-1 is refuelled at Roosevelt Field, Long Island, New York, in 1941. [Ingenium]

The company didn’t give up on Gregor’s intriguing creation, believing it could serve elsewhere in the world. For publicity, the FDB-1 participated in the Bernarr Macfadden New York-to-Miami air race in January 1940, but retired when forced to land at Hadley Airport in New Jersey with engine oil-pressure troubles.

Can-Car pressed on. The sales team hit the road on a marketing drive, with some success. Mexico expressed interest in manufacturing the aircraft under licence in 1940, but Ottawa nixed its export without any explanation.

A new marketing opportunity arose in 1941: a demonstration at New York’s Roosevelt Field to another potential foreign client. It was flown by Fred Smith, then of Canadian Colonial Airways, who called the FDB-1 “chubby in a vicious way” and said it had “the stance of a young English Bulldog.” He too had been delighted with its “feather-touch” handling, which he termed short but swift and responsive. “This was some bird!” he wrote in an Air Classics article.

Following the demo, Smith reported a tentative offer of “a colonelcy in a South American nation’s air force if I’d train a squadron in these aircraft.” That never came to pass. Clearly someone watching the performance had been awed, but still no entries appeared in the company’s order books.

There is no record of Can-Car promoting the FDB-1 much after that. With a dismal 24.5 hours of flying time on the airframe, Gregor’s dream fighter languished in a hangar in Dorval, Que., until sometime between 1944 and 1946 when it was destroyed in an accidental fire. Gregor’s patience seems to have run out long before that—he quit Can-Car shortly after RCAF interest evaporated, and moved back to the United States, eventually landing a job with Chase Aircraft Company. He retired to Trenton, N.J., and died in 1953.

“The FDB-1 represents the last of the biplanes built as first-line military aeroplanes, before the monoplane became exclusively established for this purpose,” said Britain’s authoritative publication The Aeroplane Spotter in its Nov. 2, 1946, issue. “[It] had a maximum speed comparable with other contemporary fighters, at the same time having that extra manoeuvrability which would count in a dogfight, and also a low landing speed, 57 miles per hour, making only small landing areas necessary.”

Can-Car’s production lines went on to build more than 1,400 Hurricanes for the war effort.

Advertisement