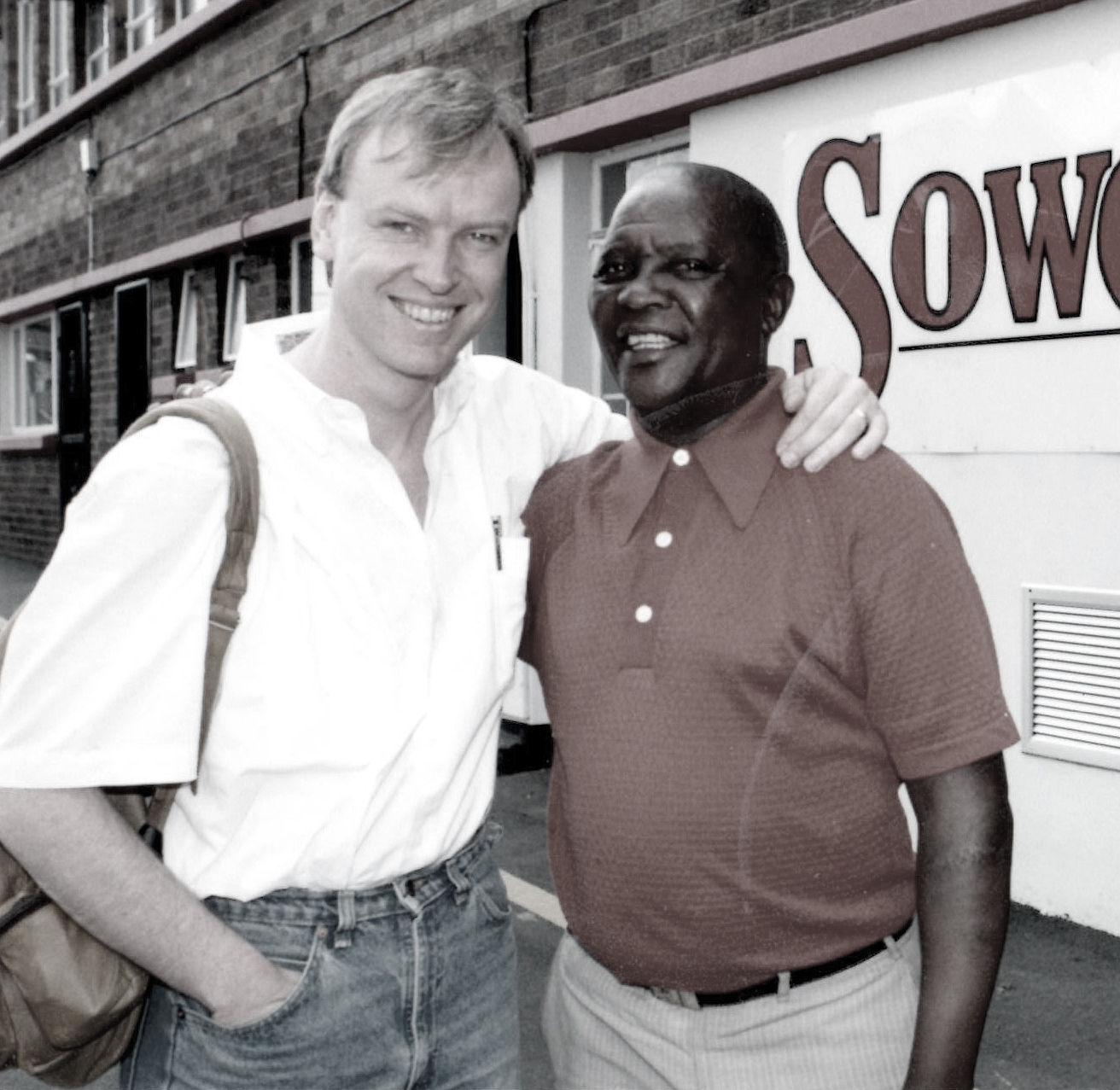

Author Stephen Thorne with Noah Makone in Soweto, South Africa, in 1994. [Stephen J. Thorne]

I regularly visited and ate in the home of my fixer Noah Makone in Soweto and talked at length with his friends and neighbours about life under apartheid and their hopes for the future.

I drove those same neighbourhoods on patrol with a white, two-man unit of the dreaded South African Police, their pistols stuffed between their legs and the capped box of their white Toyota pickup truck crammed with weapons of every description.

It was a very different perspective, and experience.

At one point, we found ourselves in the middle of a race riot. The rioters had trashed a white-owned delivery truck, using its own load of bricks to smash it and pummel its black driver. Now dismounted from our vehicle, we were nearly set afire as three Molotov cocktails landed in succession within three metres of us.

But the most disturbing experience I had was while covering a parade and rally by members of the Afrikaner Resistance Movement (AWB), a white-supremacist paramilitary organization in some ways like the militias that attended the recent rally in Charlottesville, Va.

The AWB’s members were almost exclusively descendants of the early Dutch settlers of South Africa. Most were poorly educated, and many of them were battle-hardened mercenaries who had fought against the inevitable tide of black rule in Rhodesia, Namibia and elsewhere in southern Africa.

Their symbol was three sevens formed to look like a swastika in black, white and red. Sevens, I was told, because they one-upped the devil and his three sixes.

The rally was right out of 1930s Germany. It was a very emotional experience for me, realizing with the gravitas of first-hand experience that this kind of movement could still openly exist in the world after all the effort and sacrifice that had been made to eradicate it between 1939 and 1945.

The AWB wanted a separate state in South Africa, an exclusively white nation. They wanted to relocate the Zulus and other native black Africans to “homelands” that were virtually resource-less and disadvantaged.

They claimed not to be racist, just pragmatic. But as I rode back to Johannesburg with one of their generals, he explained to me the concept of the African killer bee.

He described how the African killer bee was a hardy breed—tough, hard-working and productive. He said other strains of bee could not be allowed to dilute the species or it would no longer thrive. His story was a sick analogy to his world view.

The hatred in South Africa was immediately evident. The greater story may have been complicated but, really, the issue was black and white.

U.S. Marines provide security as members of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police Forensics Team investigate a mass grave site in Kosovo in July 1999. [Sgt. Craig J. Shell/Wikimedia]

A brief NATO bombing campaign in 1999 had set the stage for a graduated withdrawal, by sector, and I linked up with an armoured Canadian reconnaissance group that was monitoring it. As first in, last out, they had a front-line view of the carnage as it occurred.

By Day 2 of the withdrawal, Albanians were already starting to return to their homes. Frank Gunn, a CP photographer, and I returned to the Macdonian border and found a family who came from a town “liberated” by the Canadians.

We followed them home and Frank photographed the mother as she wept in the rubble of her living room where the Serbs had defecated on the floor, urinated on the walls and smashed or taken everything of value. Other homes had been booby-trapped, so that returning Albanians would be killed or maimed when they arrived.

A few days later, I accompanied a couple of combat air patrols in underpowered Griffin helicopters flown by Canadian air force pilots and manned by Canadian army observers. We flew over multiple burning homes and fields littered with bloated, slaughtered cattle.

These were Serb homes and Serb cattle, destroyed by Serbs who didn’t want Albanians to reap the spoils of war. I had never seen such hatred.

Finally, the reconnaissance unit I was with came upon a standoff at an intersection. Before us sat a busload of Serb soldiers along with three transport trucks loaded with booty. They were surrounded by troops of the British 7th Armoured Division—Montgomery’s fabled Desert Rats—who had their .50-calibre machine guns trained on the vehicles while their commander stood talking to his Serbian counterpart.

I walked over and introduced myself to the British commander and asked: “So, are these the guys who’ve been doing all the lootin’ and burnin’ around here?”

The Brit nodded to the Serb and said: “Why don’t you ask him, he speaks perfect English.”

I didn’t miss a beat. I turned to the Serb and said: “Well?”

“It’s a complicated story,” he said. “There’s a lot more to this than meets the eye.”

He went on to reference a multitude of wrongs he said were committed by Albanians against Serbs over centuries and centuries of conflict. It was more than a brief interview could comprehend, the stuff of post-doctoral studies.

The point was, it wasn’t black and white, the Serbs may have looked like the bad guys at that particular point but they had been wronged too. Memories are long, and I wasn’t there to judge. You can watch all the Second World War and Vietnam documentaries you want, I just knew—and still know—that I had never experienced first-hand hatred of that depth or magnitude before. Or since.

A Canadian soldier greets Afghan children. Soldiers would often speak with residents to build trust and gather information. [isagmedia/flickr]

There was hate, but by the hospitable tenets of the Pashtun culture from which the Taliban arose, you rarely felt it and, when you did, it was evident in the soulless gaze of the haters whom you knew could just as well kill you as look at you.

In Kandahar, I would regularly pass by people in the street who would look at me and slowly run their index finger across their throat. And mean it.

I greeted a man at a meat stand in a small village north of Kabul once with the words “As-salāmu ʿalaykum” (peace be upon you), expecting the standard reply, “waʿalaykumu as-salām” (and upon you, peace) and instead received the wordless stare.

We were on our own—my fixer, my driver and an off-duty policeman I’d hired for the day. We had gone to see some buzkashi (Afghanistan’s national sport) played on the open plains in northern Afghanistan. Now we were headed back.

Almost immediately, my bodyguard came running to fetch me, hustling me back to our vehicle and out of there at high speed. It was a Taliban village, it turned out, and word had come down that a posse was forming up to come get us.

I’m not sure many of the haters knew what or why they hated—I know some I was able to talk to weren’t even aware of the 9/11 attacks—but that lack of connection, that hateful, unreachable gaze from somewhere so deep is always unnerving.

I have seen it several times. And I have felt seething, deep-seated hate directed both at me and at others—in South Africa, in Kosovo, in Afghanistan. It doesn’t go away easily or quickly.

There is only so much we, as a so-called civilized society, can do when confronted with it in other parts of the world. The history is just too much. One thing is for sure, though: we are a continent of immigrants and we don’t want that hatred here.

That is the way it is. There is no going back.

Advertisement