When he was a teenager in the early 1900s, Torontonian Gordon V. Thompson regularly sang gospel at his mother’s missionary meetings and dabbled in writing verse. Honing his creative talents and with the help of his brother’s print shop, by age 21 he had published 10 evangelical Life Songs, which he and his buddies peddled door-to-door.

With the outbreak of war in 1914, the content of his songs quickly changed. Picking up on public fervour, he spotted an opportunity—and switched from the religious to writing songs appealing to the patriotic and sentimental. Two of his first were the 1915 compositions “When Jack Comes Back” and “Where is My Boy Tonight?”

He was not the only one.

Songwriting had recently become a popular thing to do. Pianos were common in the living rooms of most middle-class families, and schools taught the basics of music. It was before radio and television, when families would often gather around the piano in the evening to play, sing and socialize. So when the creative urge struck a housewife, accountant or whomever, they were often inspired to write a song.

With the declaration of war, the nature and content of these compositions shifted focus almost overnight. Themes that had long inspired Canada’s songwriters, such as the vastness and beauty of the country and the wealth and opportunities of its resources, were metamorphosed. Patriotism took over; loyalty to King and Empire. War became the prominent theme. Reflecting the public mood, songs were overwhelmingly patriotic or heroic.

As the fervour grew, sheet-music publishers were keen to print and promote them. Three to six pages long on light cardboard paper, sheet music was the ideal and affordable standard format for single song production. Popular publishers included A. Cox & Co. Music Publishers and Dominion Music Co. of Toronto.

Nat D. Ayer plays piano for members of the 4th Canadian Division mess in July 1918. [DND/LAC/PA-002790]

Momentum grew by the month. In Vancouver, accountant and businessman Charles F. Harrison wrote and published several patriotic songs. The first was a lively two-step march called “The Best Old Flag on Earth.” That flag is clearly the Union Jack, as a colour illustration of it makes up the entire front cover of the sheet music. On the last line of the chorus, in which the lyrics read “For the maple leaf, our emblem dear,” the piece refers to “The Maple Leaf Forever,” which at the time was Canada’s unofficial anthem.

Harrison ensured his tunes had a sales outlet as well: copies of “The Best Old Flag on Earth” were available at Fletcher’s music store in Victoria in early 1915.

Maple leaves aside, the Union Jack, Empire and King continued to dominate song themes. Another example is the 1915 composition by Albert E. McNutt and M.F. Kelly titled “We’ll Never Let the Old Flag Fall.” Its rousing chorus was typical:

We’ll never let the old flag fall

For we love it the best of all

We don’t want to fight

to show our might

But when we start,

we’ll fight, fight, fight

In peace or war, you’ll hear us sing

God save the King,

God save the King.

A few compositions weren’t new but recycled. “A Handful of Maple Leaves” by William Westbrook was popular during the South African War. For the Great War, it was updated simply by substituting ‘Belgium’ for ‘South Africa’ in the second verse accompanied by a minor adjustment to the score.

Sheet music for “The Best Old Flag on Earth” by Charles F. Harrison was popular during the First World War. “Somewhere in France” by Herbert Ivey was another popular song. [University of Western Ontario]

Many of the composers were amateur, but professional songwriters continued to produce while offering their services to the less skilled. For example, arrangers Jules Brazil and Arthur Wellesley Hughes helped by polishing dozens of amateur creations as well as composing in consultation. Professional musician Lieutenant N. Fraser Allan, who performed in the famous Dumbells troupe, was another.

Some songs evolved as the war went on. Herbert Ivey’s successful song “Somewhere in France” was reworded and printed at least nine times, according to the printer’s copies from the Whaley, Royce & Company files, held at Library and Archives Canada. As the war progressed, alternative lyrics were included for the last verse: “…for he doesn’t advertise / and God bless him where he lies / Somewhere in France” became “for he doesn’t make a fuss / pray God send him back to us / from Somewhere in France.” In its final printing, the original lyrics were omitted entirely.

The early 1915 spectre of a protracted war did little to dampen the songwriters’ enthusiasm. Reflecting popular opinion, many turned to themes of recruitment with titles like “Sons of the British Empire: Your Country is Calling You” by Harrison, and E. Cottington’s “Come! Boys! Come!” which urged men of fighting age to “respond to the call.” Interestingly, many of the compositions appealed to the powerful role of the mother as recruiting agent.

The full cast of the Dumbells’ Concert Party comes together for the closing number of their show in France. [DND/LAC/PA-005734]

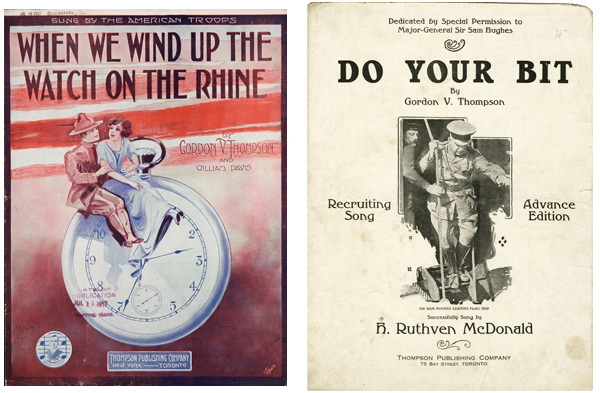

Some of the recruiting songs were more direct and practical. In 1915, for example, Thompson penned and published “Do Your Bit (for the Red, White and Blue)” as a recruiting song especially for the 204th (Toronto Beavers) Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. A sample line: “Ask yourself the question: Is it right to stay, when our men are dying fast in blood-stained France today?”

Gracing both the front and back cover of the song sheet was the uniformed image of Lieutenant-Colonel W.H. Price, Commanding Officer, who was also a sitting member of the Legislative Assembly of Ontario. On the front cover, a promise: “The entire profits of this edition go to the 204th for recruiting purposes through kind arrangement with Thompson Publishing Co., 75 Bay St., Toronto.” On the back were Price’s words of appeal: “Now don’t be satisfied with having sung the song, but get busy and do it.” It seemed to be effective. One local paper reported the 204th was soon signing up 450 men per month.

Also in 1915, the recruiting song “Canada for Empire” by Violet Bridgewater and Laura Lewin was published by the Anglo-Canadian Music Company in Toronto. In 1916, “The Canadian” by Edward Parsons and J.A. Shanks was published in England. The latter drew a clever analogy designed to appeal to Canadian spirits. With his pioneer background and super abilities, the song’s eager Canadian protagonist is ready to blaze a trail, just as “he did when the Klondike was young and a trail o’er the Rockies he flung.” But this time, the trail is to Berlin.

Many of the writers were British immigrants who held strong feelings of allegiance to the old country even after years in Canada. One of them was assistant postmaster John F. Leonard of Salmon Arm, B.C., who self-published his recruiting composition “Rally Round” during the first few months of the war. His effort had a twist: In February 1916, he acted on his own song and enlisted at Kamloops. He went overseas with the 172nd Battalion and served in England.

A few recruiting songs were aimed at shirkers and slackers—men who hadn’t answered the call to arms. Favourites included “There’s a Fight Going On, Are You in It?”, “He’s Doing His Bit—Are You?” and George Warnicker’s 1915 “Why Don’t You Wear a Uniform?” The slacker became a common public target once it was realized the war wasn’t going to be a short one.

Gordon V. Thompson was a popular songwriter of the period with hits such as “Do Your Bit” and “When We Wind Up the Watch on the Rhine.” [University of Western Ontario; Library of Congress/2014570070]

Other songs had small additions to tug at the heartstrings. The cover of the 1915 “Good Luck to the Boys of the Allies,” composed and self-published by Morris Manley of Toronto, sported an image of what appears to be a female family member about six years old. The caption alongside it read, “Sung by Little Miss Mildred Manley, Canada’s Greatest Child Vocalist.” It became immensely popular, and was recorded by both Victor Records and Columbia Records. An arrangement was recorded by the Victor Military Band, and another appeared on piano rolls.

Many musical compositions of the war years were only performed locally or privately and are now known only by their titles. For example, wartime concert programs of the Victoria Ladies’ Musical Club list performances of Kate Paget-Ford’s “For the Empire” and A.J. Gibson’s “Watchdog of Old England.” Club conductor J. Douglas Macey also performed his musical accompaniment to John McCrae’s classic poem “In Flanders Fields.”

There were other B.C. songs written primarily for a home audience. A jaunty two-step composed by Vancouver policeman Harry Shaw and fireman George Chalmers entitled “I’m Only a Khaki-Clad Soldier and I Hail from Old B.C.” envisions a soldier “from the land of the lofty pine” singing while on night patrol. The message of the cover picture is not clear however: smoke from a burning church obscures a classic mountain scene, but the soldier on duty in the foreground looks to be in no danger as he gleefully sings on.

Thompson was one of the most prolific with his war songs. Indeed their titles reflect the progress of the war year by year: “Where Is My Boy Tonight?” (1915), “Red Cross Nell and Khaki Jim” (1916), “When We Wind Up the Watch on the Rhine” and “Heroes of the Flag (the New Veteran’s Song)” (1917) and “You Are Welcome Back at Home, Sweet Home” (1919).

Later in the war, the introduction of conscription didn’t end the composing. In January 1918, Florence Ballantyne, daughter of the Speaker of the Ontario Legislature and a university professor’s wife, composed “The Call We Must Obey” to counter conscription’s unpopularity among the majority of draft-age men.

However, conscription songs were few; by then there were signs the public was tiring of war. Songwriters’ output slowed or shifted themes. Charles Harrison had enthusiastically published B.C.’s first patriotic song in 1914 but his final publication of the war, in 1917, instead harked back to the golden prewar years. With a nostalgic cover of beavers and maple leaves, “My Own Dear Canada” makes no reference to the war still raging in Europe.

To what extent the songs inspired young men to march on down to the nearest recruiting centre, or influenced public reaction to the war, may never be known, but they tell an important story of Canada’s public face and social values of the war years.

Advertisement