While training for war in Putney, England, Canadian soldiers also attended the Khaki University of Canada, where they formed a rowing club on July 6, 1918. [DND/LAC/PA-005466]

Canada’s Great War is often viewed through the lens of the costly and traumatic experience of trench warfare. Soldiers were mired in the mud, shelled, bombed and gassed daily as they scrambled to don gas masks and take cover. With little chance of striking back at their tormentors, soldiers watched their comrades killed and maimed all around them, leaving the front lines on stretchers or carried out as corpses.

And yet life at the front was far more complex. There was always more boredom than terror, although the latter was remembered as it seared the soldiers’ souls. Sentry duty, digging trenches and the seemingly never-ending task of filling sandbags to shore up crumbling trench parapets consumed much time and energy. There were nighttime raids and dawn stand-tos, both usually with a blessedly stiff shot of rum as a reward.

The boredom was met with all manner of leisure activities, including reading, letter writing, singing and other aspects of the unique soldiers’ culture. But even with these coping mechanisms, many soldiers realized that some of their best years were being wasted, and they yearned for some way to prepare themselves for postwar life.

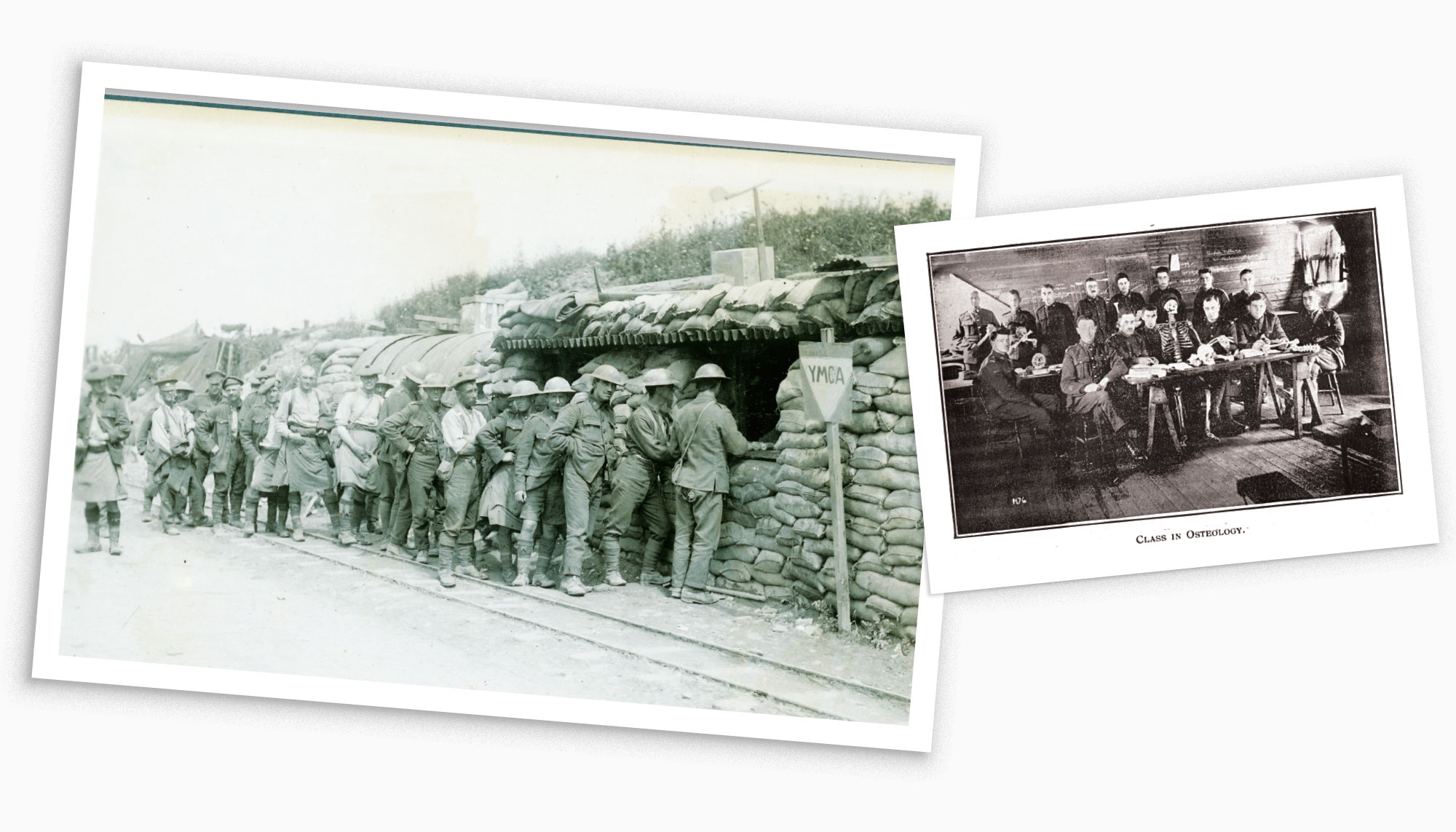

The YMCA, the Salvation Army and the chaplain service were essential groups that worked to meet the needs of the soldiers. Spiritual aid was thought to keep those in uniform from the clutches of gambling, drinking and prostitutes, while also helping them cope with the strain of service. The YMCA and Salvation Army raised millions on the home front to create, by the midpoint of the war, sports teams, cinemas, coffee stalls and other recreational sites behind the lines.

As the war dragged on with no end in sight, soldiers increasingly asked for opportunities to better themselves. The chaplains stepped in, first with Bible study groups and then in 1916 with a more formal program of educational study in partnership with the YMCA. As several hundred thousand Canadians crossed the Atlantic to train in Britain and serve at the front, the numbers of Canadians seeking access to education overwhelmed the YMCA and chaplains.

In January 1917, the YMCA requested that a representative from the Canadian universities be sent to England to help develop an educational program. That July, Henry Marshall Tory, president of the University of Alberta, went overseas on an education mission.

Osteology students pose with a bony classmate (top right). Soldiers queue up for reading material at a YMCA hut (opposite top) back from the front line. [Canadian War Museum]

Tory was born at Port Shoreham, N.S., on Jan. 11, 1864, and was awarded one of McGill University’s earliest doctoral degrees in science. But he would make his career as an educational administrator and builder. He was the right person to instigate a formal education system overseas: strong-willed, idealistic and a visionary. Over the late summer, Tory studied the existing ad hoc program of instruction, consulting with the educators and meeting with the soldiers.

Surveys were conducted to determine what the men hoped to learn. Even though the average education level for the Canadian soldiers was Grade 6, there was a fierce desire by thousands to improve themselves while overseas.

Tory noted that at one camp “fifty-seven of them wished to take up the study of agriculture, forty had their minds turned toward the Christian ministry, thirty to get a business education, eighteen to take up work of the character done by the YMCA, fifteen the study of practical mechanics, several the teaching profession, while the remainder simply desired to improve themselves.”

This was a wide variety of professions and occupations, but large numbers of men said they wanted to prepare themselves for civilian life. One Canadian officer told Tory of the value of education for those in uniform, “If you can help me and my comrades get back in touch with life at home again by giving us a chance to pick ourselves up, we will regard it as the greatest thing that can be done for us.”

There was also support from the high command. “In the minds of the military authorities,” wrote Tory in one report, education would be of “great benefit to the soldiers from the point of view of efficiency as soldiers and of general morals.”

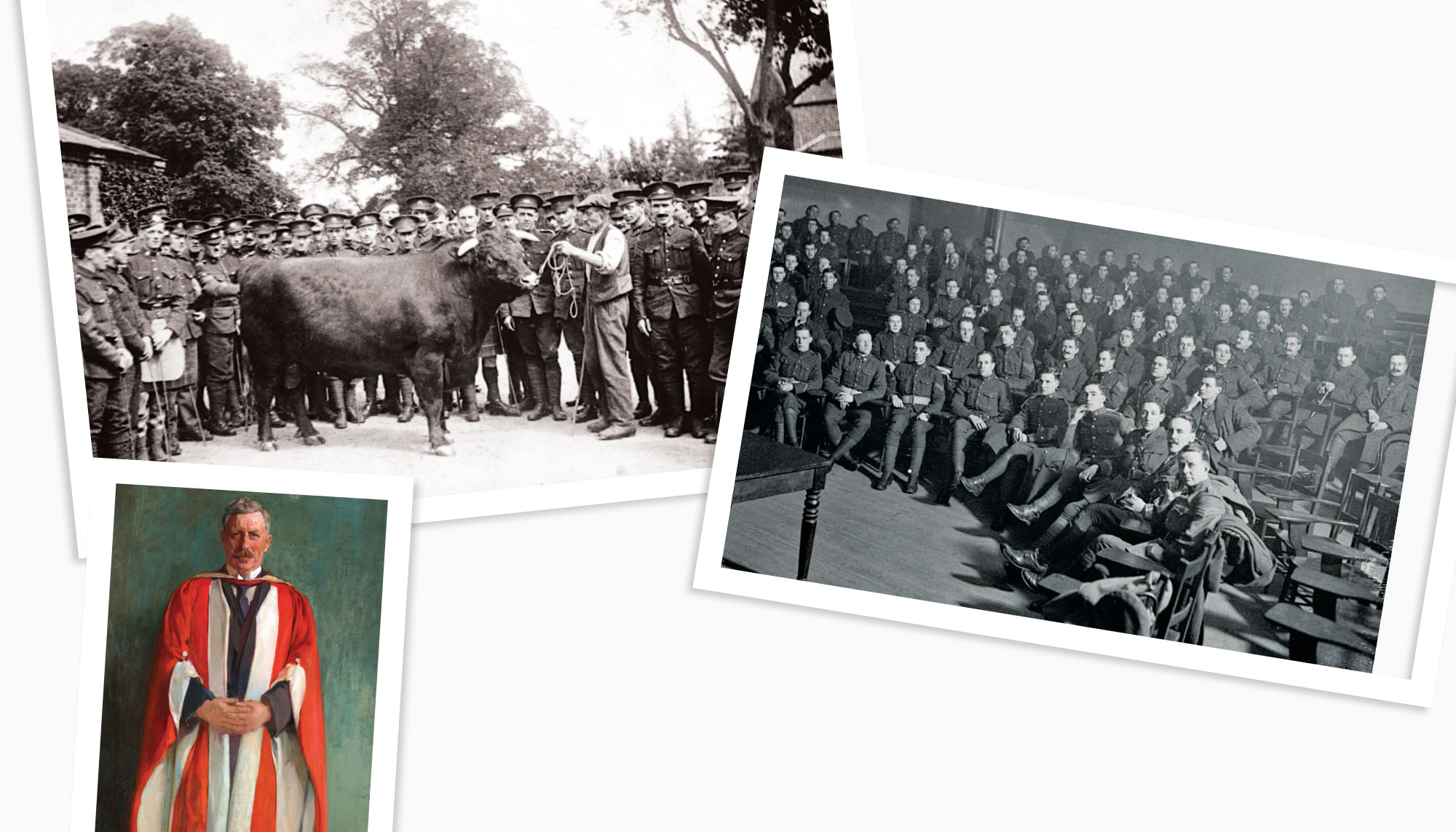

A Khaki University blazer crest (above) was worn on students’ on-campus recreational dress, consisting of shirt, tie, grey flannels and blue jacket. The prime minister received a report (top) on the university written by educator Henry Marshall Tory. [Canadian War Museum]

With instruction deeply tied to religion under the YMCA and chaplains, Tory shifted the focus to secular education, as he had done at the U of A. This put Tory and his emerging program in direct conflict with the religious groups, who soon worried that Tory, with his extensive contacts in Canada and his single-minded determination, was wrestling the education system away from them.

In fact, he was. Harry Kent of the 17th Reserve Battalion, a professor at Dalhousie University prior to enlistment who also helped develop courses for the YMCA educational program, urged the YMCA’s continued involvement.

“It has looked after the souls and bodies of the men in a splendid way,” wrote Kent, “and now if this mental need, this hunger to learn something, which is so apparent among the men, can be met by this new work, another big step forward will have been taken.”

But Tory edged out the YMCA as part of the formalization of what he would call the Khaki University, and he emphasized education instead of the salvation of souls. But Tory was no less evangelical in seeing education as imbuing the Canadian soldier with a new motivation to make a new Canada; in his words, this new program could be a “starting point of a great forward movement, not only in agriculture and industry, but in the spiritual, educational and political life of Canada.”

From late 1917, the emerging Canadian education program had one main centralized university camp for students in London and a number of colleges in the various Canadian training camps for lower levels of education. Libraries were created too, both for men in the colleges and for units in the field. The courses were a mixture of hands-on training, lectures and reading groups, ranging from men who were illiterate through to university-level instruction.

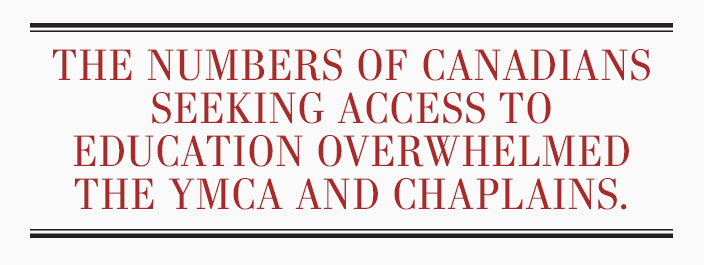

The most popular course was scientific farming, which included information on crops and management, types of soil and livestock, elementary veterinary science, dairying, and vegetable and fruit growing. These skills were all the more important as news circulated among the soldiers that they could take advantage of postwar western land grants. Almost 25,000 would do so after the war, although the work was hard, the land poor and dreams died fast for many.

While some YMCA officers continued to instruct, the majority of the teachers were drawn from the units and were a mix of officers and enlisted men. They almost always took on these responsibilities in addition to their more soldierly duties. The army of citizen-soldiers had all manner of educators and teachers in the ranks, and they stepped forward to instruct their comrades, including future professors of history, Harold Innis and Frank Underhill. Innis would use his time between pulling together lectures to finish his master’s thesis, while Underhill described his educational work as “paradise.”

Other instructors roamed the front and rear areas, providing lectures much as the emerging entertainment groups were putting up theatres and mounting plays. In fact, sometimes the two were combined, although it was tough for a lecturer speaking on the glory of the British Empire while men were waiting for the Dumbells vaudeville troupe to perform their songs and skits.

While there were some diffident instructors (and students), the skill of the teachers was often praised. The commanding officer of the 102nd Battalion was quite surprised at how popular the lectures were among his rank and file, and he noted that one visiting professor—Captain N.A. Imrie—was “able to keep the attention of several hundred healthy men for an hour or so at a time and to impart a fund of useful information whilst doing so is an art in itself.”

In December 1917, the University of Vimy Ridge (UVR) was established as one of the colleges in France, with the first classes in January 1918. Teachers were culled from the units and gave their lessons in abandoned mine offices, focusing initially on technical and agricultural instruction, as well as remedial reading for soldiers.

Henry Marshall Tory (above) was president of the University of Alberta before turning his attention to educating soldiers. Agriculture students inspect a bull (top) during a visit to the Royal Farms at Windsor Castle. A Khaki University class assembles (right top) in London in February 1918. [F.H. Varley/Varley Art Gallery of Markham/City of Markham; DND/LAC/PA-022734; PA-005190]

While this was a period of relative quiet along the Western Front before the Germans launched their massive series of offensives starting on March 21, 1918, there were shortages of school texts and classroom supplies. The soldier-teachers improvised and carried out their duties. As one report observed, “lectures are delivered and classes taught even with shells whistling overhead.”

The courses were temporarily stopped after Canadian formations were rushed to battle in March. They started up again in early summer but were done within a month, as the fighting intensified for the Canadians, especially from August to the Armistice of Nov. 11. After the ceasefire, the UVR opened new classrooms and resumed teaching.

In England, there was a more stable teaching environment for the tens of thousands of soldiers there, especially after the expanding program was recognized in Ottawa with an Order-in-Council on Sept. 19, 1918. The educational organization was named the Khaki University of Canada and Tory received the rank of honorary colonel. Shortly afterward, a public appeal in Canada to raise half a million dollars was rapidly achieved and surpassed, and a mass teaching effort was unleashed.

Promotional phrases like “Rations for the Mind” and “Don’t Starve Mentally” were used by the Khaki University to advertise to the Canadian soldiers. Administrators found students in the hospitals and recovery centres, using casualty lists to locate the wounded men who were facing long periods of monotony. Special courses were developed to help those affected by shell shock, with instructors offering speech remediation for those who stuttered or had lost the ability to speak. Educators even canvassed the venereal disease hospitals for possible students, the hope being that they would push this “difficult group,” as one report cautiously noted, “to more intellectual pursuits.”

The Khaki University administrators felt it was important to retrain soldiers from their years in the army where they had been told to accept all orders. At Ripon in North Yorkshire, where a wide variety of university courses were offered to more than 850 students, one publication implored the soldier-students to break their bovine-like ways and return to being “thoughtful youths” who will return to Canada with an “opportunity to show that you have not forgotten how to think and act for yourselves.”

These sentiments were echoed by other instructors. Major R.W. Brock, senior officer of the Khaki College at Seaford in East Sussex, noted that the soldiers’ wartime focus on survival had caused many to “starve mentally.”

With the idea of bettering Canadian soldiers, the Khaki University also taught 3,000 illiterate men to read and write. This was an empowering act for men who had spent much of the war struggling to communicate with loved ones and often relying on their mates to write letters for them. In one classroom, a Canadian soldier proudly showed instructors the first letter he had written to his wife since being separated for several years. While some of the illiterate men had neither the inclination nor interest, hundreds were instructed and came back to Canada with new skills, one of the unintended positive aspects of the war experience.

There were also courses offered to the fiancés and wives of soldiers. Thousands of Canadian soldiers married British women during the war, and the Khaki University developed a course at the University of London to instruct 250 of these women. The goal was to turn war brides into “ideal Canadian settlers,” with instruction in home economics, farming and general knowledge about Canadian geography, history and culture. One student testified that the courses “increased my self-confidence and reasoning powers and altogether has helped me to become a more useful member of the community.”

Frank Cousins, a prewar teacher wounded in 1918, wrote to his mother on Nov. 12 about the key question of all soldiers: “How soon will we get home?” He hoped to be back to Regina by the summer, but in the meantime, “I must get started on some regular work at the Khaki College right away.”

After the Armistice, education, along with sports and increased leave, were crucial tools for senior officers to ensure that their restless soldiers were steered away from the potential evils of drink and prostitution. At the same time, there was a fear in Canada that the young boys who went overseas as innocents had been hardened into killers and were unfit for society. The education program was a way to show those at home that the soldiers could and were being trained for, as Tory said, “their readjustment into civil life in Canada.”

Tory and his fellow educators felt it was their duty to instil in the returning soldiers a pride in the country for which they had fought during the war.

“We must give the diverse elements of our population some conception of Canadian ideals, Canadian history and Canadian responsibilities,” said one educator in a widely circulated memo to guide instruction. Education offered “a wider and loftier vision of our standards of life and common citizenship, the welfare and happiness and strength of the people would be greatly advanced and a splendid contribution made to the Canadianisation of our too heterogeneous population.”

Another famous lecturer, George Wrong of University of Toronto, who had lost a son in the war, wrote in The Varsity Souvenir, a publication for the Khaki College at Ripon, “Because of the war, the Canadians have passed through a rapid process of finding themselves…. The war has made Canada a real nation.”

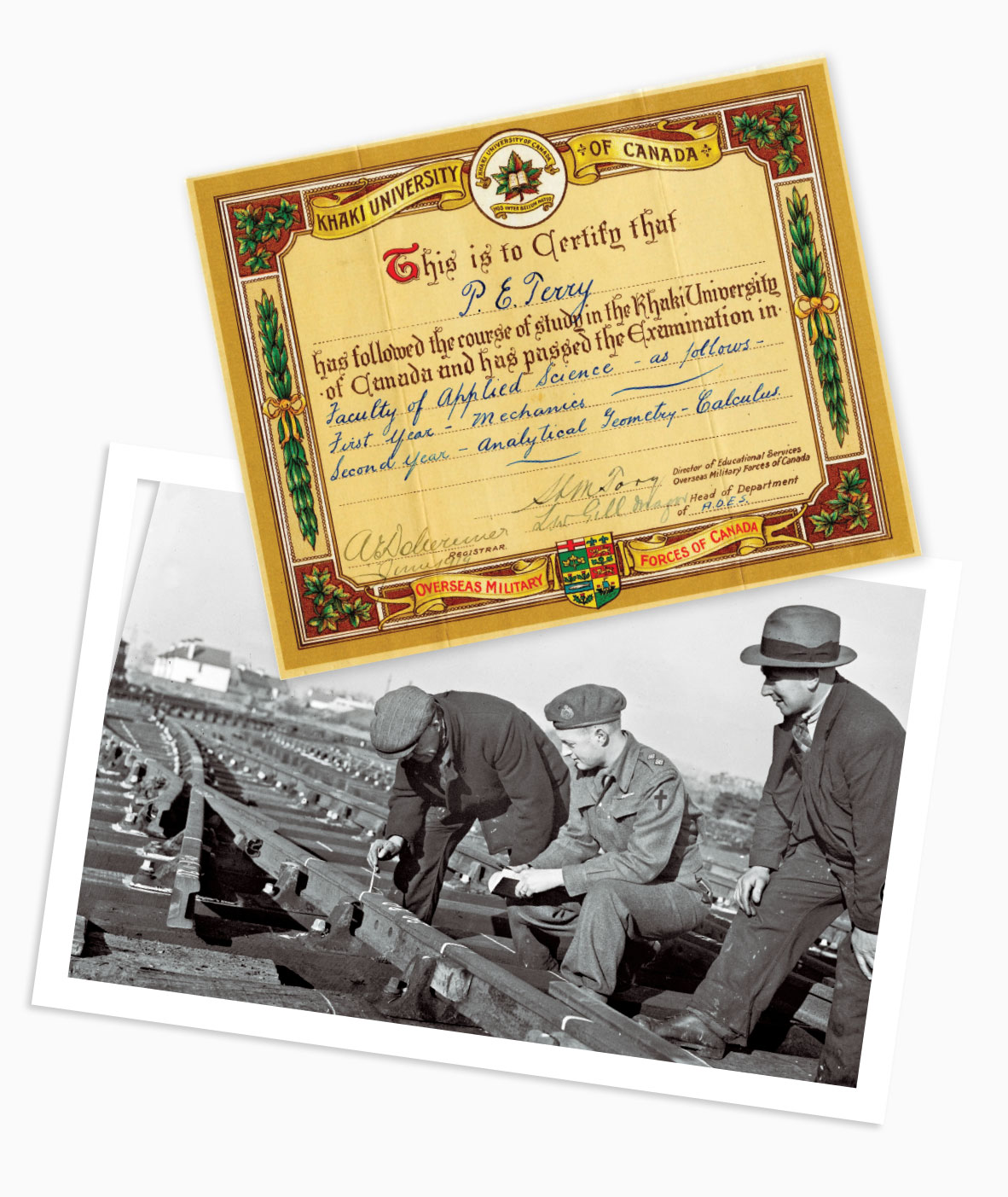

Khaki U student Lieutenant F.S. Hutton (above) receives instruction in rail removal and repair in Mitcham, England, in 1946. The education program was resurrected in the Second World War. A Khaki University diploma (top). [Harold D. Robinson/DND/LAC/PA-189306; CWM/19810561-001]

The Khaki University continued to educate tens of thousands of soldiers during the long and frustrating demobilization process. It was a grim time in Europe and Britain, with strikes, unhappiness and hardship, along with the deadly influenza strain that stalked soldiers and civilians alike. Hundreds of Canadians in uniform died from the virulent and lethal flu, and this added to the growing apprehension of returning home. A series of Canadian soldiers’ riots in England, including a deadly two-day affair on March 4-5 which led to the deaths of five and the wounding of many more, caused much disquiet among British authorities. Out of fear of future soldiers’ unrest, they fast-tracked the Canadians through the demobilization process.

The classrooms steadily emptied by the spring of 1919. The Canadian Chaplain Services remained angry with Tory, but he was able to deflect most of the charges against him—primarily, that he had focused on higher education while the chaplains had been more interested in junior educational courses. The numbers seemed to bear out Tory’s attention to both low- and high-functioning students—the vast majority of pupils benefited from instruction directed at high school- or primary school-level education, and only about 1,150 received university courses at Ripon or at British universities.

Notwithstanding the sniping from the flanks, Tory had won over the Canadian military high command with his impressive program and with the perception that education had assisted in raising morale during the difficult demobilization process. As one official military report noted, “the Khaki University has met and is still meeting a deeply felt want among the men of the Overseas Military Forces of Canada.”

The Khaki University held its last class on June 30, 1919. From the Armistice until then, 50,189 soldiers had enrolled in courses and more than 500,000 had attended lectures. Tens of thousands more had benefited from education during the war. This was a wild success by any measure, and the educational experiment prepared thousands of soldiers for life in postwar Canada.

Tory’s vision, energy and drive had led to an extensive teaching program to aid the soldiers, and after the war he returned to the University of Alberta, and then went on to create colleges that became the University of British Columbia and Carleton University.

The impact of the Khaki University has largely been displaced from social memory, but tens of thousands of Canadian veterans returned to their communities better armed with skills and knowledge gained at the university, especially as they faced the much anticipated and frightening prospect of what they might do for the rest of their lives.

Advertisement