During the Second World War, a desert-based commando unit of the British Army employed bold, innovative guerilla tactics to wreak havoc on German forces in North Africa. The Special Air Service and its exploits, including present-day counterterrorism, hostage rescue and other covert operations, are the stuff of rogue heroes.

This is not that story.

This is the tale of the Canadian Special Air Service Company, a distinctly different organization made up of airborne soldiers whose initial role in postwar Canada was non-military: airborne firefighting, search-and-rescue and aid to the civil powers.

“The story of the Canadian SAS Company is actually surreptitious,” wrote Bernd Horn in his 2001 paper,

A Military Enigma: The Canadian Special Air Service Company, 1948-1949. “The army originally packaged the sub-unit as a very benevolent organization.

“Once established, however, a fundamental and contentious shift in its orientation became evident—one that was never fully resolved prior to the sub-unit’s demise. With time, myths, often enough repeated, took on the essence of fact.”

SAS members expected to form a special operations unit practised in long-range reconnaissance, deep penetration raids through enemy lines in conventional warfare and supporting guerrilla or irregular forces in unconventional warfare.

The unit had no insignia of its own. Assembled as the Cold War was declared, its 125 infantrymen came from the country’s three regiments, some of them war veterans from the vaunted 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion or the Canada-U.S. First Special Service Force, famously known as the Devil’s Brigade.

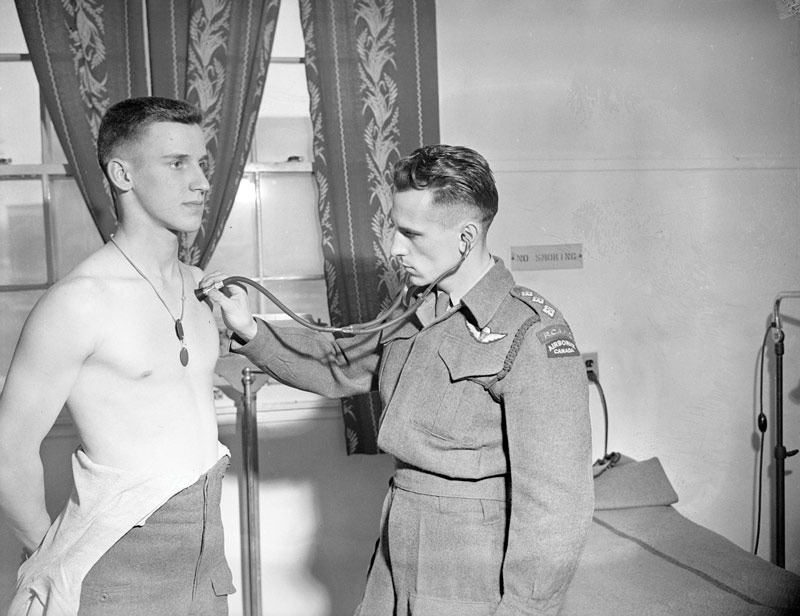

They retained their original regimental badges and underwent rigorous preparations for their anticipated role as a high-flying elite force. They trained in rope work, survival, mountaineering, improvised demolitions, skiing and foreign languages.

The Canadian Special Air Service Company lasted but two years,

its only operations a 1947 Arctic rescue and flood relief in B.C. in 1948.

They were chosen for their “superb physical condition…demonstrated initiative, determination and self-reliance.” And they had to be unmarried.

“Exercises were reportedly rigorous, with scenarios usually involving an airborne raid on a fixed enemy installation,” reported canadiansoldiers.com. “At least one member of the Company was killed during a public parachute demonstration.”

They were commanded by a decorated Devil’s Brigade veteran, Captain Lionel Guy d’Artois, a temporary appointment who, after his wartime commando unit folded, volunteered to join the Special Operations Executive in 1943. He jumped into France under the codename Dieudonné and spent the rest of the war organizing, arming and operating with units of the French Resistance.

d’Artois’ tenure as acting officer commanding of the new unit proved short. The search for a permanent replacement was still going when the unit was shut down.

The Canadian Special Air Service Company lasted but two years, its only credited operations a 1947 Arctic rescue mission for which d’Artois, the lone SAS soldier involved, was awarded the George Medal, and flood relief in British Columbia’s Fraser Valley in 1948, the only time the service functioned as an entire unit.

The military disbanded the SAS in September 1949 and created the Mobile Striking Force, a larger and more conventional airborne unit. Some SAS members were retained as instructors, augmenting existing training establishments until the strike force was formed. Others returned to their regiments.

d’Artois went on to serve with the Commonwealth occupation force in Japan, then did an operational tour with the 1st Battalion, Royal 22e Régiment, during the Korean War.

“Something was clearly amiss. Either the sub-unit was named incorrectly or its operational and training focus was misrepresented.”

The story of the Canadian Special Air Service Company might be all but lost to popular history, however the facts ring familiar today, when Canada’s military is mired in controversy, recruitment is languishing and the government wants to cut the defence budget by almost $1 billion.

Then, as now, the military’s role in civil affairs and crisis response was up for debate and funding was in short supply.

In the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, the powers that be in Ottawa had little concept of what they wanted to do with the country’s armed resources.

The vast, sparsely populated land that had entered the war with meagre military might ended it with the world’s third-largest navy and one of the largest air forces. Its shipbuilding industry, virtually non-existent in 1939, was among the planet’s biggest. Yet all of it was reduced to nominal strength after the fighting ended.

Even the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, a standout in the formative years of airborne warfare, was disbanded six weeks after Japan surrendered.

Global affairs were changing fast and so were opinions on how to address them.

“Notwithstanding the military’s achievements during the war, the Canadian government had but two requirements for its peacetime army,” wrote Horn.

“First, it was to consist of a representative group of all arms of the service. Second, it was to provide a small but highly trained and skilled professional force which, in time of conflict, could expand and train citizen soldiers who would fight that war.

“Within this framework paratroopers had limited relevance. Not surprisingly, few showed concern for the potential loss of Canada’s hard-earned airborne experience.”

In the austere postwar climate of minimum peacetime obligations, Horn added, the fate of Canada’s airborne soldiers, who would typically form the core of any commando unit, “was dubious at best.” The Canadian Parachute Training Centre in Shilo, Man., had stopped prepping new jumpers virtually as soon as the war in Europe ended in May 1945. Its future hung in the balance as it awaited a final decision on the direction the postwar army would take.

“No one knew what we were supposed to do,” recalled Lieutenant Bob Firlotte, who had been hand-picked to serve at the centre, “and we received absolutely no direction from army headquarters.”

Nevertheless, senior staff worked to keep abreast of airborne developments and perpetuate the links forged with American and British airborne units during the war. Horn called their efforts “the breath of life” that the airborne advocates needed.

Their advocacy would eventually pay off after a National Defence Headquarters study revealed that British peacetime policy was based on training and making all infantry formations air-deliverable. Americans and Brits alike made it known they would welcome an airborne establishment in Canada capable of “filling in the gaps in their knowledge.”

These “gaps” included the problem of standardizing equipment between Britain and the U.S., and addressing the need for cold-weather research.

“Canada seemed to be the ideal intermediary for both needs,” wrote Horn. “It was not lost on the Canadians that co-operation with its closest defence partners would allow Canada to benefit from an exchange of information on the latest defence developments and doctrine.”

A test facility might not be a parachute unit, but it would allow the Canadian military to stay in the game. Ultimately, National Defence opted to form a joint parachute training school and airborne research-and-development centre in Rivers, Man.

“For the airborne advocates,” said Horn, “the Joint Air School, [later to become the Canadian Joint Air Training Centre] became the ‘foot in the door.’ More important, the JAS…provided the seed from which airborne organizations could grow.”

Still, the concept of a special operations force, which showed such promise in the fleeting Devil’s Brigade, was all but lost entering the Cold War—“a patchwork of activities, few of which were co-ordinated in any fashion,” according to Sean M. Maloney, a history professor at Royal Military College in Kingston, Ont.

Once the army’s permanent structure was established in 1947, impetus to expand airborne capability began to stir at the Joint Air School. In May 1947, the school proposed the Canadian Special Air Service Company with its clearly defined benevolent role.

The army backed the idea, calling the unit’s inherent mobility a definite public asset for domestic operations and a potential benefit to the country. The SAS, it said, would provide an “efficient life and property saving organization” capable of moving to any point in Canada in 10-15 hours—not unlike the role the military’s present-day Disaster Assistance Response Team plays on the world stage.

The official Defence Department report for 1948 noted that co-operation with the Royal Canadian Air Force in air search-and-rescue would meet International Civil Aviation Organization requirements.

The initial training cycle consisted of four phases, covering research and development (parachute-related work and field skills); airborne firefighting; air search-and-rescue; and mobile aid to the civil power (crowd control, first aid, military law).

“Conspicuously absent was any evidence of commando or specialist training which the organization’s name implied,” wrote Horn. “The name of the Canadian sub-unit was a total contradiction to its stated role. It was also not in consonance with the four phases of allocated training.

“Something was clearly amiss. Either the sub-unit was named incorrectly or its operational and training focus was misrepresented. Initially no one seemed to notice.”

The director of weapons and development added two additional roles when he forwarded the request for the new organization to the deputy chief of the general staff: “public service in the event of a national catastrophe” and “provision of a nucleus for expansion into parachute battalions.”

“This Company is required immediately for training as it is these troops who will provide the manpower for the large programme of test and development that must be carried out,” the proposal noted.

There was no mention of special forces or war fighting. But by October 1947, mission creep began to rear its head. Embedded in an assessment of potential benefits that the company could provide to the army was an entirely new idea.

“The formation of a SAS Company,” the report explained, “is in line with British Army Air Group post war plans; whereby the SAS is being retained as a small group integrated within the Airborne Division. This provision is to keep the techniques employed by SAS persons during the war alive in the peacetime army.”

It appeared last in the list’s order of priority but, in practice, it would soon become the primary objective.

Things changed virtually as soon as the defence chief approved the SAS proposal in January 1948. “Not only did its function as a base for expansion for the development of airborne units take precedence, but also the previously subtle reference to a war fighting, special forces role, leapt to the foreground,” said Horn.

“The shift was anything but subtle. The original emphasis on aid to the civil authority and public service functions, duties which could be justified to a war-weary government and a budget conscious military leadership, were now re-prioritized if not totally marginalized.”

Horn described the change as partially a case of gamesmanship, allowing the strong airborne lobby within the Canadian Joint Air Training Centre and others in the army with wartime airborne experience an opportunity to perpetuate a capability that they believed was at risk.

“The Special Air Service originated during World War II when after numerous operations military authorities were convinced that a few men working behind enemy lines, could, with sufficient bluff and daring wreak havoc with supplies and communications,” said a historical report for the Joint Air School.

“Results obtained during the war assured its continued existence.”

Said Horn: “The report was not only incorrect in its assessment of the value placed on special operations type units during the war, but more importantly, it clearly reflected a war fighting rather than public service orientation.”

Each of the company’s three platoons was made up of members from one of the country’s three infantry regiments: the Royal 22e Régiment, the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (PPCLI) and The Royal Canadian Regiment.

d’Artois trained his carefully selected paratroopers as a specialized commando force. According to Horn, SAS vets said their commander “didn’t understand ‘no.’ He carried on with his training regardless of what others said.”

“Guy answered to no one,” said one.

“He was his own man, who ran his own show.”

Higher up, however, there was varied opinion and interpretation of the unit’s role.

“The central issue remained,” said Horn. “Was the SAS Company in fact the nucleus of a larger airborne force? Was it designed to be an elite commando unit? Or was it just simply a demonstration team for the Canadian Joint Air Training Centre? Evidence exists to support each perspective.

“This confusion was merely a symptom of a larger problem, namely there was no clear understanding or agreement of the role the paratroopers were to fulfill. It was characteristic of the blight that has permeated the entire Canadian airborne experience over the years.”

The cash-strapped Canadian political and military leadership came to realize that the kind of postwar concept that was emerging among Allied nations—smaller standing forces with greater tactical and strategic mobility—could check all their boxes.

“It provided the shell under which the government could claim it was meeting its obligations, yet minimize its actual defence expenditures,” said Horn. “In essence, possession of paratroopers could represent the nation’s ready sword.

“They afforded a conceivably viable means to combat any hostile intrusion to the North. Better still, they would be incredibly cheap, if they were maintained simply as a ‘paper tiger.’”

Not unlike its present-day commitments to NATO, Ottawa had made defence promises to its Allied partners it had not kept, particularly the Americans, to whom it was to provide an airborne/air-transportable brigade, and its necessary airlift, as its share of the overall continental defence agreement.

Yet, after more than two years, nothing had been done. By the summer of 1948, pressure was mounting. Finally, National Defence granted authority to start training.

Major-General Churchill Mann, the vice-chief, visited the PPCLI battalion in Calgary and asked it to convert to airborne status. Training, he told the troops, was to start in three months and must be completed by May 1949.

“The effect was profound,” Horn reported. “The unit in its entirety volunteered for airborne service. The first concrete step to establish the airborne/air-transportable brigade, as required by the 1946 Basic Security Plan, had finally been taken.”

The effect on the small SAS Company was “immediate and corrosive.” The unit initially lost its PPCLI platoon—permanently removed from the SAS and returned to Calgary to provide its parent battalion with a core of experienced para instructors.

A replacement platoon was raised from the service support trades, but the writing was already on the wall. The SAS Company was doomed. Its personnel were increasingly commandeered as instructional staff for the training scheme to convert the two remaining infantry battalions into airborne/air-transportable units.

In September 1948, with the creation of the Mobile Striking Force already underway, the director of military training demanded a reassessment of the SAS Company.

“I cannot agree with what appears to be the present concepts of the SAS Company,” he declared, noting the contradiction between its original intent and the actual practice.

“No one knew what we were supposed to do and we received absolutely no direction from army headquarters.”

“I feel first and foremost that its name should be changed…it is true that in war they [special forces type units] do produce a result out of all proportion to their aims, if properly employed; but they do not win battles; they are a luxury and it is very much doubted if they, in their true sense, can be recruited from our peacetime armed forces.”

A month later the defence chief announced his intention to disband the Canadian SAS Company as soon as the 22e Régiment finished its airborne conversion training, the last of the infantry regiments to do so.

The posting of personnel to the SAS Company simply dried up.

“It should be noted that, in view of the present policy, the AG [Adjutant General] Branch regards the SAS Co. as a wasting commitment and is loath to post personnel to fill existing vacancies in it,” complained the army.

There was a reprieve, however brief, but in the end Canada’s Special Air Service sputtered out of existence, its obscure legacy a link perpetuating airborne culture and skills from their wartime roots to a new generation of paratroopers.

Advertisement