The Canada Aviation and Space Museum’s First World War aircraft collection is considered among the best in the world. It includes multiple one-of-a-kind and rare period planes.

[Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

Warplanes started out as rudimentary aircraft with open cockpits and limited instrumentation. Pilots, quite literally, flew by the seat of their pants—without parachutes.

The aviation industry was in rapid growth, in constant evolution, improving designs and performance.

There were more than 50 different aircraft designs during the First World War, with five distinct technological generations. The combatants produced over 200,000 aircraft and even more engines. French industry accounted for a third of them.

By war’s end, Allied nations were outproducing the Germans by nearly 5:1 in aircraft and better than 7:1 in engines. Britain was coming out with 31 times more planes a month than it had owned when the war started. The Royal Air Force was not only the first independent air service, but also the largest.

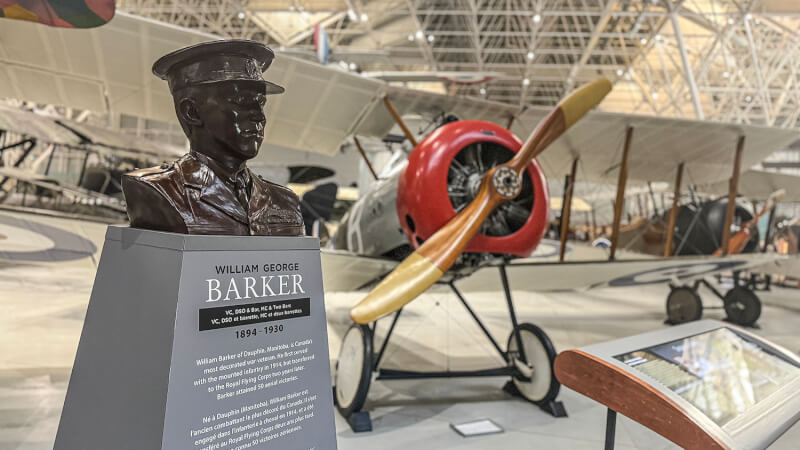

The collection includes an original Sopwith Snipe (foreground) of the type flown by Canadian William Barker during the Oct. 27, 1918, action that earned him a Victoria Cross. Sitting to the left of this aircraft is an example if his primary foe that day, an original Fokker D VII, built by Fokker itself in 1918. Barker was bounced by 15 of these German planes from Jagdgruppe 12. He destroyed three, along with a two-seat Rumpler, before he was forced down inside Allied lines with severe wounds.

[Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

Flying with British units, Canuck aviators nevertheless acquitted themselves exceptionally well in history’s first aerial confrontation between nations.

There were 171 Canadian flying aces between 1914 and 1918—airmen with five-plus aerial victories, or kills. Four of the Top 12 were Canadian, three of them Top 10: Billy Bishop with 72 kills; Raymond Collishaw (60); Donald McLaren (54); and William Barker (50). Twenty-four Canadians scored 20 or more; four were awarded Victoria Crosses; 193 received Distinguished Flying Crosses, plus six bars.

Barker is credited with 50 aerial victories. He was killed at age 35 in a 1930 crash at the very airfield, Rockcliffe, where the Canada Aviation and Space Museum now sits. He was the most decorated Canadian serviceman of WW I. Besides a VC, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order and Bar, the Military Cross and two Bars, two Italian Silver Medals for Military Valour, and the French Croix de guerre. He was also mentioned in dispatches three times.

[Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

They were displayed at the Deutsche Luftfahrt Sammlung (German Aviation Museum) in Berlin during the 1930s before it was destroyed, along with many of Goering’s planes, in an Allied bombing raid. The surviving aircraft, their wings removed and never recovered, were transported by train to a Polish forest, where they sat in railcars until they were recovered by local authorities and stored until 1963. Considered the most extensive collection of WW I aircraft in the world, the wingless planes are now displayed in the Polish Aviation Museum in Kraków.

Designed to replace the legendary Camel, fewer than 100 Snipes reached France before the end of WW I. The Canada Aviation and Space Museum’s aircraft was manufactured in 1918 by Nieuport and General Aircraft Ltd. of England, and is believed to have served abroad. It was imported to California by actor and former Royal Flying Corps pilot Reginald Denny and featured in several movies, possibly including the 1930 Howard Hughes classic Hell’s Angels. The museum bought the restored plane in 1964.

[Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

The collection includes multiple rare and one-of-a-kind WW I aircraft, including such recognizable names as Camel, Snipe, Nieuport, Fokker and Junkers. There’s also a pristine restored 1918 Curtiss JN-4 “Canuck,” which museum curator Erin Gregory calls “a cornerstone of Canadian aviation.”

The Fokker D.VII was designed in 1917 by the chief designer at Fokker Flugzeug-Werke GmbH, Reinhold Platz. Powered by a Daimler Mercedes D.IIIav, 160 hp, in-line engine, it was a resilient and agile aircraft for its time, considered one of the war’s best fighters. It was easy to manoeuvre, with excellent control characteristics at slow speed and could fly easily in thin air—ideal for novice aviators. It was designated for postwar destruction in the 1919 Versailles Treaty, although several were smuggled out of Germany into the Netherlands. This aircraft was one of 142 shipped to the United States for the U.S. Air Service. It was later sold for civilian use and featured in several movies, including Hell’s Angels. It is one of seven surviving D.VIIs and the only one of them built by Fokker. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

A variant of the legendary Sopwith F.1 Camel, the 2F.1 Ship Camel was produced specifically for the Royal Naval Air Service with more powerful engines and modified armament. Entering service in 1917, the Camel replaced the Sopwith Pup. The name was derived from the hump-shaped cover on which the machine guns are mounted. The naval 2F.1s were flown from barges towed behind destroyers, from platforms on the gun turrets of larger ships, and from early aircraft carriers. This one was manufactured by Hooper and Co. Ltd. of London in late 1918, one of the last Camels to be produced. It did not serve in WW I, but it was used by the RAF until 1925, when it was transferred to Canada along with six other Ship Camels.

[Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

Developed at the Royal Aircraft Factory in Farnborough, England, the Scout Experimental 5, or S.E.5, was one of the fastest aircraft of the war. Stable and relatively manoeuvrable, it has been described as “the Spitfire of World War 1.” The S.E.5 outperformed the Sopwith Camel but was less responsive to the controls. Together with the Camel, the S.E.5 was instrumental in regaining Allied air superiority in mid-1917 and maintaining it for the rest of the war.

[Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

An original Lewis machine gun mounted on the wing of a WW I S.E.5a at the Canada Aviation and Space Museum in Ottawa. Guns mounted on the fuselage, directly in front of the pilot, required synchronization with the spinning propellor. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

A predecessor to the renowned Nieuport 17, the Nieuport 12 was used for WW I reconnaissance and as a fighter and escort to French heavy bombers. Flight Sub-Lieutenant Arthur Ince was flying a Nieuport 12 when he became the first Canadian to shoot down an enemy aircraft during the First World War. Built in 1915, this Nieuport 12 was gifted to Canada by the French government. It is one of only two known to exist worldwide.

[ Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

The Sopwith Triplane had excellent manoeuvrability and optimal pilot visibility. It was in wartime service for less than a year but still managed to inspire several German triplane designs. Serving with the all-Canadian B Flight of No. 10 (Naval) Squadron, Triplanes downed 87 enemy aircraft between May and July 1917. Called the Black Flight because of the black markings of their airplanes, their aircraft were named Black Maria, Black Sheep, Black Prince, Black Roger, and Black Death. This replica was completed by American Carl R. Swanson in 1966.

[Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

Built in 1918, the museum’s Avro 504K includes a Turnbull variable-pitch propeller. The innovation, which would become standard equipment on aircraft, was first tested on an Avro 504 at Ontario’s Camp Borden June, 29, 1927.

[Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

The Junkers J.I was the world’s first all-metal aircraft to go into production. Its forward fuselage was covered with steel plates, making it almost impenetrable to ground fire. While several aircraft were lost in landing accidents, none was reported destroyed in combat. A war trophy shipped to Canada in 1919, this is the world’s only surviving Junkers J.I.

[Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

The straight black cross, known as the Balkenkreuz, was adopted by the German air service in mid-April 1918. Variations of the straight cross design replaced the flared “cross pattée” insignia on all German aircraft.

[Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

The Maurice Farman S.11 Shorthorn was developed just before the First World War by Farman Frères, a French aircraft company founded in 1908 by pioneering aviators Maurice and Henri Farman. A “pusher aircraft,” with the engine located in front of the rear-facing propeller, it was initially used for reconnaissance and light bombing. It later became a trainer. It was called the “Shorthorn” because it lacked the distinctive forward elevator of its predecessor, the Farman S.7 Longhorn.

[Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

The Shorthorn is distinguished by its bathtub-like cockpit, which comprises the entire body of the aircraft.

[Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

Used as a training aircraft during WW I, the Curtiss JN-4 “Canuck” would later become a favourite of barnstormers and recreational flyers. Manufactured by Toronto-based Canadian Aeroplanes Ltd., it achieved more firsts than any other Canadian aircraft, including first aircraft to cross the Canadian Rockies; first aircraft to be mass-produced in Canada; and first to deliver air mail (from Montreal to Toronto on June 24, 1918). A former U.S. Air Service plane, this aircraft hung from the roof of Edward Faulkner’s barn in Honeoye Falls, N.Y., for 30 years.

[Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

The museum purchased the aircraft in 1962 and restored it to represent a typical JN-4 of the First World War.

[Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

The museum’s JN-4 is painted in the livery of No. 85 Canadian Training Squadron, with the squadron’s distinctive black cat on the fuselage.

[Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

This A.E.G. G.IV built by Berlin-based Allgemeine Elektrizitäts Gesellschaft was shipped to Canada as a war trophy in 1919. A tactical bomber operating close to the front lines, this one is the only surviving multi-engine German aircraft of the First World War and the only existing plane in the distinctive German “night lozenge” camouflage. The G.IV was eventually restricted to night missions, usually nuisance raids intended to disrupt sleep and inflict random damage. Crews wore electrically heated suits, and the aircraft was fitted with radios. The rear gunner’s cockpit had a hinged window in the floor for viewing and fending off pursuers.

[Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

Entering service in 1912, the Royal Aircraft Factory B.E. 2 (this is the ‘c’ version) was the first British military aircraft to cross the English Channel to France after the start of the First World War. It was used mainly for reconnaissance and military observation, although some were single-seat bombers. Single-seat B.E. 2c night fighters downed six airships over Britain.[Stephen J. Thorne]

All models of the B.E. 2 had such great stability that they could nearly fly themselves during reconnaissance and artillery observation missions. This Royal Aircraft Factory B.E. 2c was built in 1915 by the British and Colonial Aeroplane Company Limited and served with No. 7 Squadron, RFC, in 1916-1917.[Stephen J. Thorne]

Advertisement