A daring mission by a Canadian-crewed Wellington bomber raised the stakes in the Allies’ battle for air supremacy

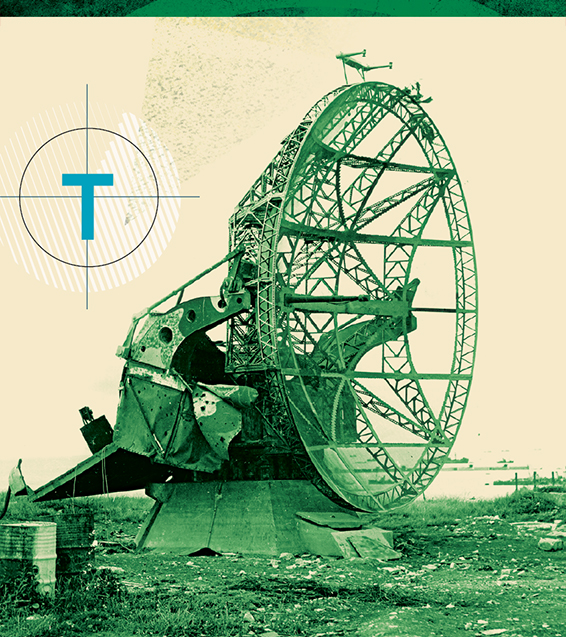

A German radar installation on the Normandy coast in France in June 1944. [Wikimedia]

In 1939, RAF Bomber Command had intended to raid German targets in daylight with unescorted bombers, but by the end of the year that plan had been shot down by Luftwaffe fighters who were directed by ground-based radar stations. The Royal Air Force’s own land-based radar system then gave Fighter Command an edge in the Battle of Britain in August and September 1940. Britain had gained a slight advantage, but the enemy was not far behind.

The Germans improved. By 1942, impressive low-UHF band Würzburg radar sites installed from Norway to the Pyrenees mountains were tracking Allied bombers into Europe night and day, before they even crossed the North Sea or the English Channel.

Many of the secrets of the Würzburg array were uncovered in Operation Biting, a daring British commando raid on Germany’s radar installation at Bruneval, France, on Feb. 27-28, 1942. Examination of the seized radar equipment revealed that it was impervious to being jammed by conventional means. By the late summer of 1942, German night fighters were finding and attacking the bombers with increasing frequency.

The RAF had been developing airborne radar since the fall of 1940, initially with “bugs,” then with greater reliability. Clearly, the Luftwaffe was developing a similar tool. But how did the German equipment operate? Did its airborne radar use the same frequencies as the ground stations? Was there a way to counter those radars?

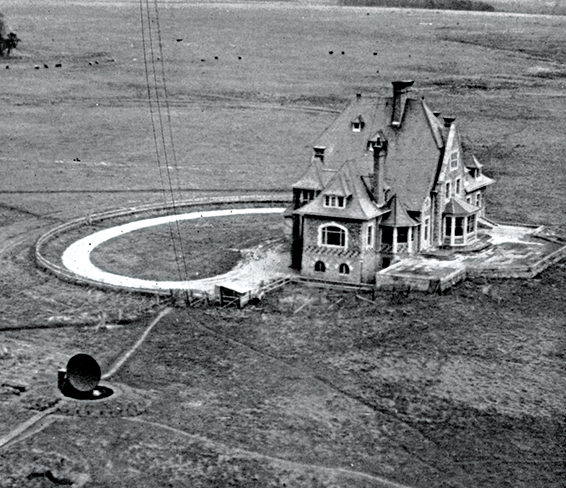

A Würzburg radar system at Bruneval, France (bottom), was photographed by RAF reconnaissance before being captured in Britain’s Operation Biting on Feb. 27-28, 1942. [Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy/JM4DKM]

Occasional intercepts of German air-to-ground night-fighter radio traffic indicated that the enemy was using an airborne radar system code-named “Emil-Emil.” There was no way to analyze this except to send deep into Germany an investigating aircraft equipped to monitor, record and retransmit enemy frequencies. The RAF aircraft would have to expose itself to the night fighters, allow itself to be detected by radar, and be attacked—all in time to report the events. Surviving the attack was of secondary importance.

Fast Mosquito aircraft would have been best for such dangerous missions, but they were not forthcoming, so Wellington bombers were used. At least 17 probing flights failed to provoke an attack. But the night of Dec. 3, 1942, was different.

Wellington DV819 took off from RAF Gransden Lodge airfield at 2:02 a.m., accompanying bombers attacking Frankfurt. They were briefed to look for German transmissions in the 490-megacycle band—the same as the Würzburg stations.

The crew that night included Pilot Officer Edwin Amos Paulton, RCAF, of Windsor, Ont., the pilot; P/O William Alexander Renton Barry, RCAF, of Russell, Man., the navigator and a veteran of at least six previous radar investi-gative flights; Flight Sergeant William Walter Bigoray, RCAF, of Redwater, Alta., a wireless operator and air gunner; Flt. Sgt. Frederick Percy Grant, RCAF, of Brockville, Ont., an air gunner; Flt. Sgt. Everitt Thomas Vachon, of Ayer’s Cliff, Que., an air gunner; and P/O Harold Graham Jordan, RAF, of Croydon, operator of the equipment that was to monitor the fighter’s radar signals.

There was nothing to report until 4:31 a.m. Paulton was about to turn for home when Jordan reported receiving signals he thought were the ones sought. He warned the crew to expect a fighter attack. The signal grew stronger and Jordan repeated his warning. Using previously arranged codes, he forwarded the frequency back to base.

Paulton committed the Wellington to a homeward run while Jordan warned the crew that his receiver was being saturated and an attack was imminent. At that moment, the aircraft was hit by a burst of cannon fire. Jordan was struck in the arm, and realizing that there was now no doubt about the signal being the correct one, he changed the coded message, a change that would tell base that the frequency given was absolutely correct and that it applied without a doubt to the signal being investigated. These messages were repeated until the Wellington’s radio equipment was shattered.

Rear gunner Vachon identified the enemy as a Junkers Ju 88, then gave Paulton a running commentary to guide evasive corkscrew turns. He fired close to 1,000 rounds but scored no visible hits before the fighter inflicted crippling damage with its 20-millimetre cannons. When his turret was knocked out, a wounded Vachon moved to the astrodome and continued to direct evasive action. The fighter came back again and again, making 10 passes in all. Paulton wrestled the Wellington about, taking it down from 14,000 to 500 feet. At last their tormentor broke away.

All the while, Jordan had been transcribing any information he could decipher about the German transmissions. Barry, the navigator, had gone forward to release Grant, now wounded, from the front turret. When Jordan was hit in the eye, he realized he could not continue the investigations much longer. He fetched Barry and tried to explain to him how to continue operating the equipment and so bring back more information. By this time, he was almost blind.

By then the Wellington was a wreck. The starboard throttle control had been shot away, the port throttle was jammed, the front and rear turrets and the starboard aileron were unserviceable, and the trimming tabs were having no effect at all. The airspeed indicator was reading zero due to a damaged pitot tube, the airflow measurement device. The starboard petrol tank had been punctured, fabric had been shot and torn away on the starboard side of the fuselage, and the hydraulics were unserviceable.

Pilot Officer Edwin Amos Paulton was the pilot on the Dec. 3, 1942, mission. [DND/LAC/PL-34005]

Flight Sergeant Frederick Percy Grant was the front gunner. [Courtesy of Hugh A. Halliday]

Despite both engines running irregularly, Paulton managed to struggle back to 5,000 feet, evade enemy searchlights near Dunkirk, and bring the bomber back to England. Reaching the English coast at 7:20 a.m., Paulton concluded that the aircraft was unsafe to land. The choice was bail out or ditch, and he gave his crew both options.

Bigoray, also wounded, said he would prefer to jump, since one of his legs had stiffened up so much that he thought he would not be able to escape the aircraft in the water. He made his way to the rear hatch, but then remembered that he had not clamped down the transmitting key. He returned to the set, clamped the key down and warned the crew not to touch it—it would be needed by rescuers trying to home in on them. He jumped over Ramsgate, the seaside town in Kent, taking with him the messages that had described Jordan’s findings, and landed safely.

Paulton ditched the Wellington in shallow water at approximately 8:24 a.m., about 200 metres off the coast near Deal. The dinghy inflated but had been punctured by cannon fire. Jordan tried to make it airtight by holding some of the holes but it was impossible. The crew got out of the dinghy and climbed onto the aircraft. About five minutes later, a small boat approached, picked them up and rowed ashore.

“All too often, acts of extreme bravery by individuals have no real effect on the outcome of a war. This one did,” wrote Alfred Price in Instruments of Darkness: The History of Electronic Warfare, 1939–1945.

On Jan. 12, 1943, the London Gazette announced that Jordan had been awarded the Distinguished Service Order, Paulton the Distinguished Flying Cross and Bigoray the Distinguished Flying Medal. In keeping with the secretive nature of their mission, the published citation was uninformative, saying only that they had “displayed great gallantry, fortitude and devotion to duty in exceptionally hazardous circumstances.” Subsequently, Barry was awarded a DFC, Vachon a DFM and Grant was mentioned in dispatches.

The mission of Wellington DV819 had informed the Allies about the nature of Germany’s FuG 202 Lichtenstein radar. Although it would be developed and improved by the enemy, British Intelligence was able to detect that evolution. They were aided in this game by the defection of a German night-fighter crew to Scotland in May 1943, bringing with them an example of the latest Lichtenstein. Their Junkers Ju 88R is on display today at the Royal Air Force Museum Cosford.

The findings of the heroic sortie enabled the RAF to equip its night bombers with devices known as “Monica” and “Boozer,” which scanned to the rear, detecting Lichtenstein transmissions and warning the crew of a fighter approaching. They must have reduced potential losses, but sadly, in the Wizard War, could not offer absolute protection. “Monica” in particular emitted its own electronic pulses; once this was known to the enemy, Luftwaffe fighters were able to track the same pulses. No amount of radar measures could deal with a fighter which either did not have radar or had switched it off prior to executing an attack. The battle of wits continued to the end.

A damaged Vickers Wellington bomber takes evasive action. Wellingtons were used in the RAF’s radar detection missions. [Peter Fong/CWM/19700218-071]

Advertisement