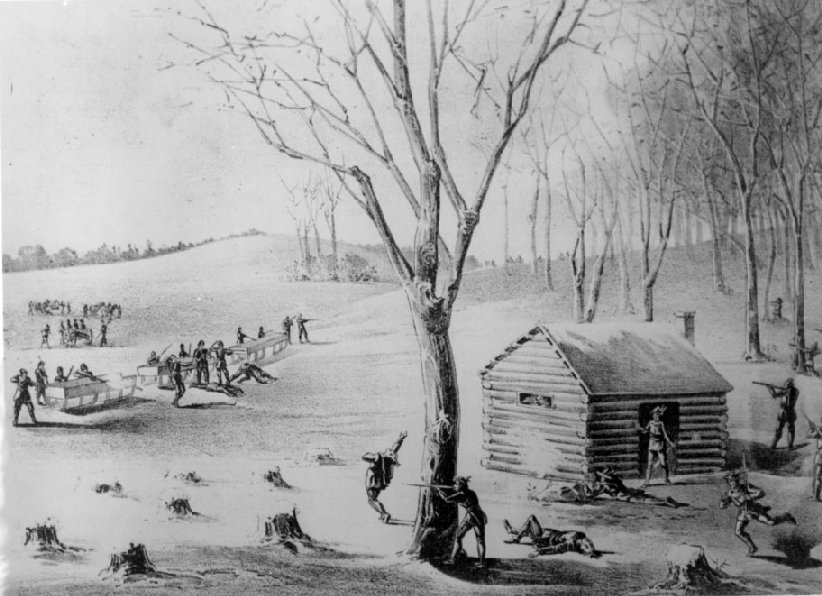

An illustration of the Battle of Duck Lake.

In the 1880s, the Canadian Prairies were a political powder keg.

Bison herds were gone, land had been signed away in treaties and indigenous peoples were starving. The Métis wanted title to their homesteads and farms, whose boundaries were ignored by government and railway surveyors. After poor harvests in 1883 and 1884, farmers were desperate. Settlers, encouraged to buy land along the rail route expected to run from Winnipeg to Edmonton, felt misled at best, cheated at worst, when the line was built instead to Calgary through Regina, commonly known as Pile of Bones until 1882.

They all felt their pleas for help went unheard in seats of power to the east.

The Métis called on Louis Riel to help. Fifteen years earlier, his successful resistence resulted in The Manitoba Act, which preserved the French language, some land for the Métis, and created the province of Manitoba.

This time, the federal government answered his petition by sending troops. In response, on March 18, 1885, the Métis formed a provisional government in Batoche, now in Saskatchewan, with Riel as president.

Tension soon turned to violence—seven battles, and one massacre—that claimed hundreds of lives. The Métis won the first battle, at Duck Lake on March 26. The violence spread as aboriginal, mostly Cree, warriors joined the fray. At Frog Lake, in what is now Alberta, Cree warriors killed eight settlers and the Indian agent, whom they blamed for starving their people.

Although the Métis and indigenous warriors were successful early on, the federal government sent 3,000 militia westward by rail to join the force of 5,000 militia and police congregating in Saskatchewan. Federal forces won the decisive battle at Batoche May 9-12 and the final battle at Loon Lake on June 3.

Riel surrendered, was tried for treason and was executed in Regina on Nov. 16, 1885.

Eleven days later, six Cree and two Assiniboine warriors were also hanged.

Canada still feels the effects of those events.

The events alerted the federal government to the need to enforce Canadian law everywhere, resulting in peaceful settlement of the West but also subjugation of indigenous peoples and their continued marginalization, culminating in the recent Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

To the Métis, Riel is a hero who fought for their rights and defended their culture. He is known as the father of Manitoba, where a public holiday is held in his honour in February. His hanging fanned the embers of French Canadian nationalism in Quebec.

Hot debates follow suggestions that he be pardoned or exonerated. There was a recent suggestion that the Ottawa building housing the office of the prime minister, which was named after a proponent of the residential school system, be renamed in honour of Riel.

Advertisement