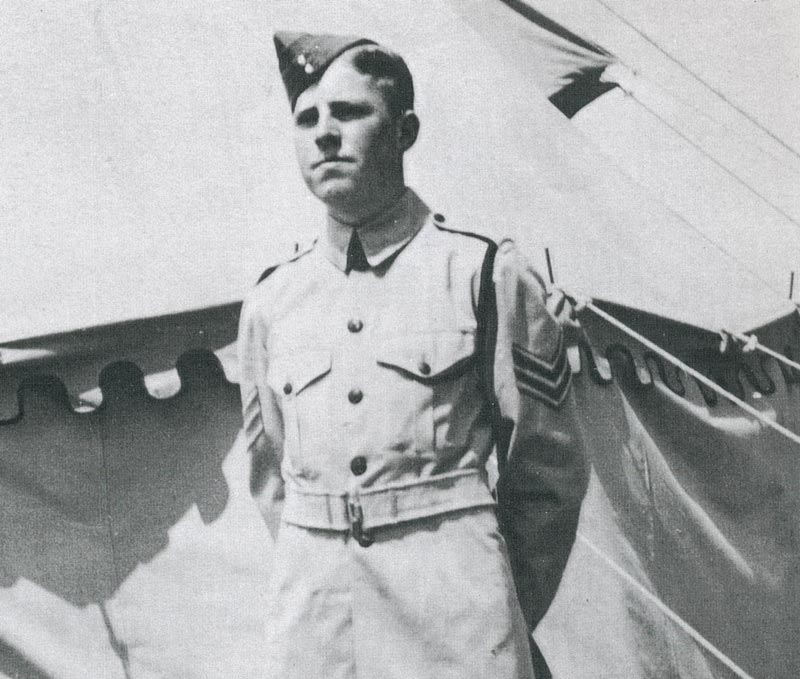

George MacDonell on his 19th birthday, only a few months before the Canadians were ordered to fight in the Battle of Hong Kong in December 1941. [The Memory Project/George MacDonell]

He joined the doomed Royal Rifles of Canada which fought alongside the Winnipeg Grenadiers when the Japanese invaded Hong Kong in December 1941. Two hundred and ninety Canadians were killed and 493 wounded in three weeks of fierce fighting.

“The most vital war effort of the Japanese, destroyed by young Canadians.”

MacDonell was among the nearly 1,200 captured. He spent close to four years in brutal Japanese prisoner of war camps, first in Hong Kong, then in Japan, where prisoners were forced to work in atrocious conditions.

Hong Kong prisoners were sent to Japan’s largest shipyard in Yokohama. They were slave labourers, but soldiers first, and bent on foiling the enemy where they could.

Group of Royal Rifles of Canada confined at the Sham Shui Po Prison Camp following the fall of Hong Kong in 1941. [LAC/PA-166579]

The prisoners were moved in April 1945 to a remote camp in the mountains of northern Japan, where they worked as slave labour in a mine until the end of the war in August.

“We were left in a very dangerous position, surrounded by hostile Japanese troops and without any arms and…in the last extremes of starvation,” MacDonell said in an interview with Veterans Affairs Canada. “I was down to something like 138 pounds.”

They knew the camp commander had orders to kill the prisoners if rescue seemed imminent. And “we also knew that we could all easily be deposited in a local mine shaft,” he wrote in a 2020 article in Quillette.

But the commander was open to negotiations, and “to our delight, local Japanese farmers were friendly” and exchanged food for items looted from the camp’s inventory.

George MacDonell stands in the back row, fourth from the left, with other prisoners of war who were held at Ohashi Prison Camp in Japan. [George MacDonell]

Two days later, they heard an aircraft. “Then suddenly he was above us—a little blue fighter with the white stars of the U.S. Navy.”

The pilot threw a silver box out of the aircraft. “Inside we found strips of fluorescent cloth and a hand-written note: Lieutenant Claude Newton (Junior Grade), USS Carrier John Hancock. Reported location.”

Using the strips of cloth, the men fashioned letters letting the pilot know they needed medicine and food; he waggled his wings and flew away.

“Seven hours later, two dozen airplanes approached from the sea,” recalled MacDonell. They dropped food and medicine, including penicillin, but “our camp doctor had understandably never heard of it.”

Several days later bombers parachuted down 60-gallon drums packed with rations, supplies and clothing. “Some of the parachute lines snapped in high winds,” he recalled, “and the oil drums fell like giant rocks. One packed with canned peaches went through a hut roof and exploded on the concrete floor. “I don’t have to describe what the hut looked like.”Once “I looked up to see that I was right under a cloud of falling 60-gallon oil drums. It was a terrifying moment. And I imagined the bizarre idea of surviving the enemy, surviving imprisonment, and then dying, thanks to the kindness of well-meaning American pilots.”

Before he left, MacDonell visited the mine where he’d worked. “I wanted to say goodbye to the foreman of the machine shop, a grandfatherly man who…had been as kind to me as the brutal rules of the country’s military dictatorship permitted. It was both joyous and sad. We were happy that the war was over, yet sad at the knowledge that this would be our last meeting.”

It took a month for rescuers to arrive. On Sept 15, 1945, they were led out of the camp by U.S. Marines.

Liberated Canadian prisoners of war aboard the hospital ship U.S.S. Benevolence, Yokohama, Japan, Sept. 3, 1945. [LAC/ PA-131532]

Advertisement