After considerable lobbying by Blacks

and their white supporters,

Canada fielded one Black battalion,

but they had

to fight with shovels,

not rifles

“I have been fortunate to have secured a very fine class of recruits, and I did not think it fair to these men that they should have to mingle with Negroes.”

Lieutenant-Colonel George Fowler, commanding the 104th Battalion, wrote these words in an attempt to have 20 new “coloured” soldiers removed from his unit. Despite official Canadian government policy to the contrary—which clearly stated Black volunteers could be accepted—many Blacks suffered rejection at recruiting stations. Amazingly, about 1,500 Blacks did manage to enrol in the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF). After two years of tireless lobbying by Black leaders, assisted by supportive whites, the government finally authorized a Black unit. The Black population of Canada at the time probably numbered about 20,000, the majority of them in Nova Scotia (7,000) and Ontario (5,000), with lesser numbers in New Brunswick (1,000) and the western provinces.

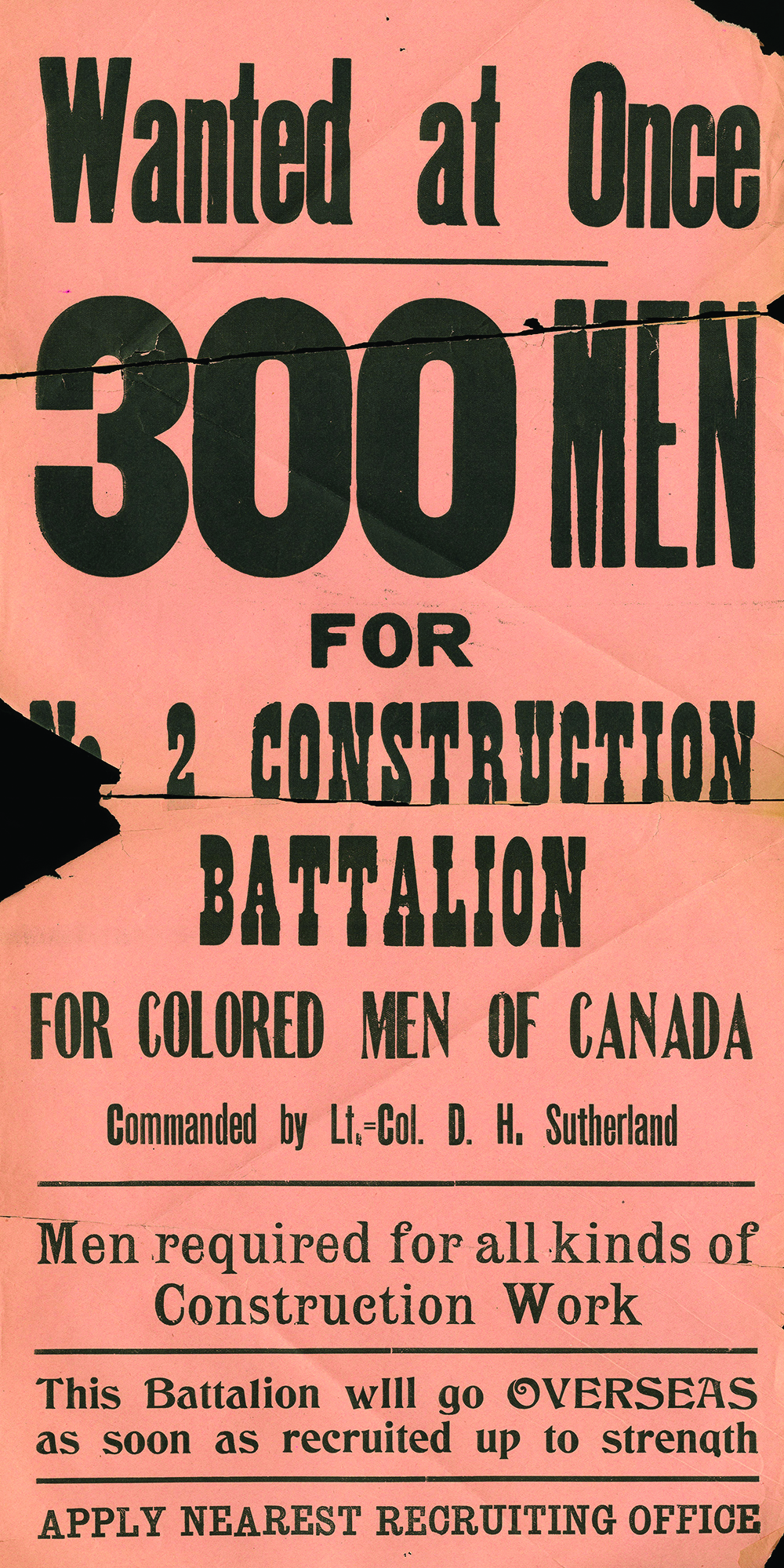

Because of its large Black population, the army selected Nova Scotia as the location of the new unit, and on July 5, 1916, No. 2 Construction Battalion was authorized with headquarters at Pictou. Canada formed three construction battalions during the First World War, a type of unit no longer used today, but very much in demand then, to carry out essential tasks. These units built and repaired trenches, roads, bridges and railways, among other tasks.

No. 2 Construction Battalion became the first and only Black unit ever established in Canada after Confederation. Notwithstanding, the officers were white, with one notable exception.

The unit chaplain, the Reverend William White, was one of very few Black officers in the British Empire during the First World War, but, as a padre, his captain’s rank was honorary. The son of a slave, White originally came from Virginia but moved to Nova Scotia in 1900 and studied theology at Acadia University, graduating in 1903. He settled in Truro and ministered to the flock of Zion Baptist Church. He was also the father of famed contralto Portia White, a classical concert singer of the 1940s and ’50s.

Padre: Captain William White was the unit chaplain, one of the few Black officers in the British Empire. [Lt.-Col. D.H. Sutherland Collection, River John, N.S.]

While the unit’s senior non-commissioned officers (NCOs) were Black, there were exceptions. The two most senior appointments—regimental sergeant-major and regimental quartermaster sergeant—were white. The reasoning was that few Blacks had leadership experience at the time, and both these individuals had previous military service. Later in the war they were commissioned as officers and remained in the unit.

Lieutenant-Colonel Daniel Sutherland, a prominent Nova Scotia railroad contractor, commanded the unit. About half the officers came from Nova Scotia and the rest from Ontario and elsewhere. Although CEF units normally recruited locally, No. 2 Construction Battalion recruited across Canada, making it a truly national unit. The initial response saw many young Blacks—several still in their teens—volunteering throughout the country.

There were 1,049 all ranks needed to bring the battalion up to full strength and the battalion soon boasted 180 recruits, quartered in a building in Pictou. After two months the unit moved to Truro, where the commanding officer (CO) felt the local Black community would help stimulate recruiting. Despite this, recruiting continued to be a problem.

The unit carried out recruiting drives across the province but met with limited success. It looked as if the battalion might not reach its authorized strength. Although Blacks now had their own unit, the segregated nature of the battalion and its non-combatant status understandably upset some of them. Previous rejection may have dissuaded others from attempting to enlist again.

Recruiting: Recruiting proved difficult before the unit departed for overseas.[Esther Clark Wright Archives Acadia University/1900.237]

Several Blacks who joined the unit felt “The army let us join, but wouldn’t let us fight. They gave us shovels, not rifles.” Incredibly, even while wearing their country’s uniform, Black soldiers continued to suffer segregation. In Truro, they had to sit upstairs in the movie theatre until some unit officers intervened.

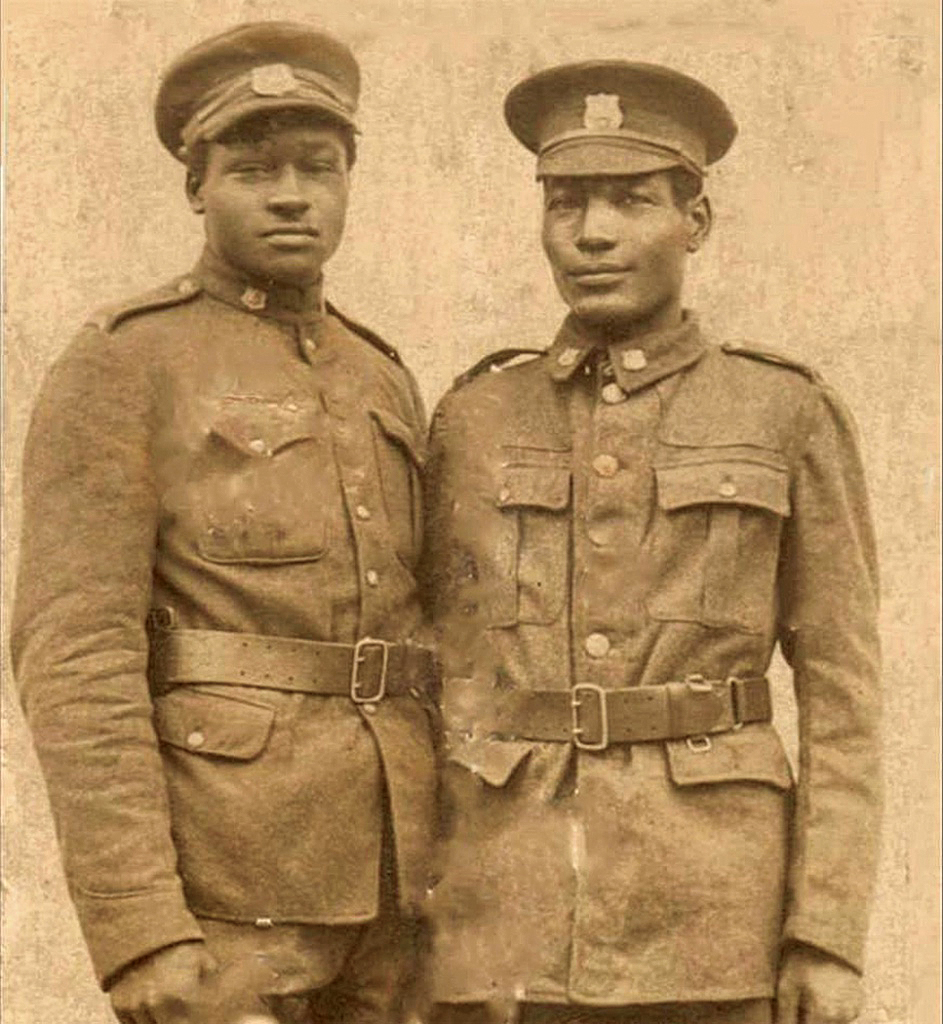

One of the pictures often used to represent No. 2 Construction Battalion (on this year’s Canada Post African Heritage Month stamp above) features Joseph Alexander Parris, the father of Sylvia Parris. Every time Sylvia sees the photograph, she notes, “It always evokes emotions for me: pride, sadness, curiosity, disappointment. Certainly, he is a strapping figure in uniform. He looks self-assured, a young man with purpose and resolve.” She reflects, “I wish I knew more about his personal journey, about the story of the battalion and its contributions to freedom.”

Incredibly,

even while wearing

their country’s uniform, Black soldiers

continued to suffer segregation.

In Truro, they had to sit upstairs in the movie theatre

until some unit officers intervened.

About 300 Blacks came from Nova Scotia; about 400 others who worked in coal mines—an essential occupation—could not join. The rest of Canada provided 125 recruits, some 20 per cent of the battalion’s final strength.

Interestingly, 163 American Blacks joined and made up the about 25 per cent. Sutherland also recruited in the British West Indies, which brought in a few more soldiers.

Despite being under strength, Sutherland received word in December 1916 his battalion was needed in France. When the unit went overseas, military authorities tried to keep it segregated, and suggested sending the battalion in its own ship. Fortunately, the navy rejected that idea and in March 1917, 624 all ranks embarked at Halifax. The men disembarked two weeks later at Liverpool and entrained immediately for their camp in southern England.

Officers: No. 2’s officers including Captain William White (front row, centre) pose. [Lt.-Col. D.H. Sutherland Collection, River John, N.S.]

While in England, the unit built practice trenches and constructed and repaired roads within the Canadian camp. The reality of war hit home when frequent enemy air raids resulted in permanent air sentries being designated.

In early May, the unit—still some 300 men under strength—reorganized as a company and Sutherland reverted to major to continue as CO. The new establishment consisted of 506 men and 10 officers.

When conscription became law in late 1917, it included Blacks.

Men who had tried to enlist only two years earlier and experienced rejection

on the basis of colour now found themselves bound by law to join.

On May 17, No. 2 Construction Company crossed the English Channel to France. It spent two depressing days in the pouring rain on a train and two more on roads before it reached Lajoux, near the Swiss border. Here, in the Jura Mountains, it spent the rest of the war.

The company was attached to No. 5 District, Canadian Forestry Corps. Soldiers of the battalion assisted four forestry companies in logging, milling and shipping. During the First World War, lumber was a much more critical commodity than in later wars, used for trenches, duckboards, gun platforms and many other items.

Some men shipped lumber sawn by the forestry companies, while a 50-man detachment assisted in logging and the construction of a narrow-gauge railway to carry logs to the mill. Another group of 100 kept the roads in good condition. From time to time, parties worked elsewhere; some of the soldiers served in or near the front lines laying barbed wire and they came under artillery fire.

The CO: Lieutenant-Colonel Daniel Sutherland was a railway contractor before the war. [Lt.-Col. D.H. Sutherland Collection, River John, N.S.]

One of the officers, Lieutenant James Hayes, a civil engineer, had served in the militia before the war. He signed up to get overseas when the war started, but when that did not happen he was “volunteered” for No. 2. Kempton Hayes notes that although his father was initially “unhappy” with this decision, he dutifully went overseas with the unit. At Lajoux, Hayes was in charge of the camp’s pumping stations and water lines.

The battalion worked hard and Chaplain White’s diary reveals his constant concern for its well-being. Yet, the unit continued to be treated like second-class citizens. It always received supplies last, and sometimes the troops did not get underwear or socks. Fortunately, the battalion had its own medical officer, Nova Scotian Captain Dan Murray (grandfather of singer Anne Murray), but when he was away, other white medical officers often refused to treat soldiers from No. 2.

Forestry: The unit worked with the Canadian Forestry Corps overseas. [Lt.-Col. D.H. Sutherland Collection, River John, N.S.]

Ironically, when conscription became law in late 1917, it included Blacks. Men who had tried to enlist only two years earlier and experienced rejection on the basis of colour now found themselves bound by law to join, and faced forcible induction or severe penalties if they failed to do so.

When the war ended, No. 2 Construction Company sailed for Halifax in January 1919, and on Sept. 15, 1920, the unit officially disbanded. Canada’s first and only Black military unit was no more.

Sylvia Parris remarks, “How I would have loved to have asked Daddy: ‘What did it feel like to sail overseas? Did you see Uncle Bill after departing the ship? Did you miss your parents?’” Unfortunately, she was unable to ask any questions before he died. “The most significant reason,” she notes, “is that this important part of Canada’s and Nova Scotia’s history was not taught to me during my time in public school.”

Enlisted: Nova Scotia brothers George and James Downey joined the battalion in October 1916. [Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia]

She thinks now of the conversations she could have had with her father: “‘Daddy, today I learned about No. 2 Construction Battalion. The teacher said we should ask our families about it.’ Imagine what sharing that may have evoked.”

In July 1993, in honour of No. 2 Construction Battalion, a granite memorial erected by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada commemorating the unit’s contribution to Canada was unveiled at Pictou’s Market Wharf. Since then, an annual memorial service has taken place at the monument honouring the men of “The Black Battalion,” who persevered against deep-rooted prejudice to serve their country with pride.

Advertisement