![COPP1 Members of Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal peer into a mine shaft used by German troops for infiltration purposes, August 1944. [PHOTO: KEN BELL, LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA—PA131353]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/COPP1.jpg)

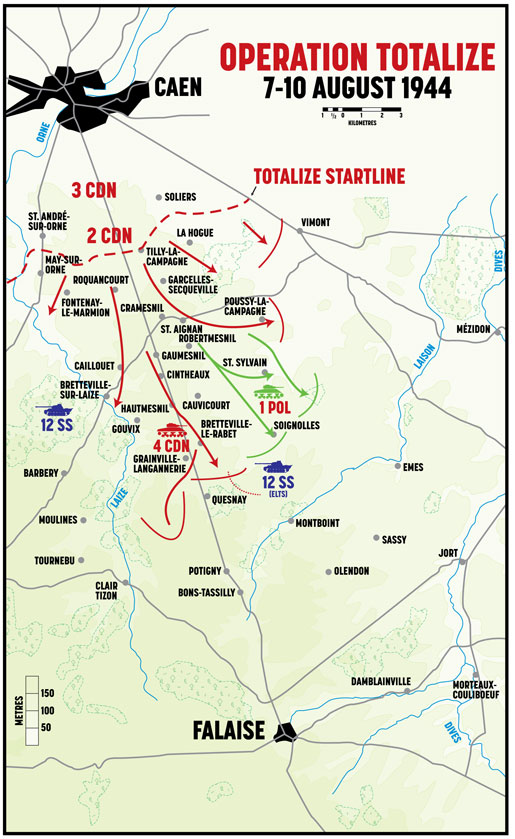

Operation Totalize was the first major action carried out by First Canadian Army in the Second World War and a great deal of attention was paid to documenting every aspect of the Aug. 8-10, 1944, battle.

Historical officers serving with each of the three divisions as well as Major A.T. Sesia, the officer commanding 2nd Field Historical Section at corps headquarters, were ordered to provide the fullest coverage.

Sesia, along with 2nd Canadian Division historical officer Captain J. L. Engler and Capt. G.D. Pepper, the divisional war artist, decided to follow the advance as closely as possible. They set up camp just behind the start line on Aug. 7. Sesia’s report, titled All In A Day’s Work, began with a description of the battlefield partly illuminated by “a waning full moon looming larger and red in the eastern sky.” Waves of bombers arrived, their bombs striking with “an unceasing rhythm of sharp explosions.” Then came the deafening noise of a full-scale artillery barrage and “the first wave of tanks, clattering and screeching into view emerging from clouds of dust like mechanical monsters in a Buck Roger’s comic strip.”

German artillery and mortar bursts persuaded the men to shelter behind a derelict tank and to wait until daylight. Sesia slept soundly for an hour before being awakened by a “furry substance”—Toty, a kitten he had found hiding in a slit trench. “During the air bombardment and artillery barrage, Toty had been content to remain buttoned up in my battledress tunic but when things quieted down I released him and he disappeared into the night… The guns meanwhile had opened up once more and the kitten without further ado crept under the blanket and settled himself against me for the night.”

At daylight they drove to St. André-sur-Orne and met troops of the Fusiliers Mont-Royal (FMR) who reported that May-sur-Orne was still in enemy hands. The village was held by German infantry supported by mortars, Nebelwerfers, and machine guns, pinning down anyone who tried to cross the open fields.

Engler interviewed two FMR officers after the battle and they offered a detailed description of their part in the operation. The main attack with the tanks and “unfrocked priests”—improvised armoured personnel carriers later known as “Kangaroos”—had torn a large hole in the German line but on both flanks the battalions of the 89th Infantry Div. had held off the initial attacks by Canadian and Scottish troops.

The advance to May-sur-Orne had begun well as the dust and smoke allowed the leading troops to infiltrate the village. The FMRs were badly under strength, and with less than 40 men per company they could not clear the houses. They regrouped and at 4:30 a.m. all four companies began a silent attack. This attempt failed as numerous enemy machine guns, posted on the flanks of the village, found targets.

While a new plan was being developed, the depleted battalion spent most of the day under observed fire from the higher ground at May-sur-Orne. Under the new plan, artillery would suppress enemy fire, and a squadron of “Crocodiles”—Churchill tanks equipped with flamethrowers—would provide a new form of close support. After the British tank crews were assured that “very few anti-tank guns or mines existed in the area” they performed aggressively, following closely behind the infantry. They opened fire on the houses with their 75-mm guns, blowing holes in the walls and shooting flame inside the buildings, forcing the defenders to flee.

The infantry searched the buildings as they were “flamed,” but it was soon evident the enemy was terrified and in full retreat, leaving mortars, machine guns and an 88-mm anti-tank gun behind. The Canadians were effusive in their praise of the British tank crews “who rarely—if ever—hesitated before taking on any job asked of them.”

Engler’s interviews with officers of the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada told a very different story of the battle for Fontenay-le-Marmion. The Camerons had to cross Verrières Ridge near its highest point and gain control of a well-defended village on the reverse slope. Their fighting strength had been greatly reduced in the previous weeks and during the advance which covered more than three kilometres. In “a night of reduced visibility, men became separated from their sub-units.” As few as 150 men reached the edge of the village.

The Camerons had also bypassed German positions during the night, and with daylight enemy counterattacks came from every direction. The Germans used self-propelled assault guns and an 88-mm to harass the Canadians, but fortunately the German infantry did not follow up in any strength. “The biggest attack, two platoons, was driven off.”

With the final battle for May-sur-Orne still ahead, it was fortunate that the third of the three villages attacked by 6th Brigade fell quickly to a determined assault by the South Saskatchewan Regiment (SSR). Lieutenant-Colonel Fred Clift, who had been serving as Acting Brigadier for 4th Bde., returned to take over the SSRs just before the advance to Rocquancourt. Clift was an inspirational leader and after the calamity that struck the battalion on July 20 (Flawed From The Start, November/December 2011) his leadership was badly needed. The battalion “leaned into” the artillery barrage all the way to the village. “Enemy heads were still underground when we arrived.” Prisoners were taken in the orchards but the battalion waited until the moon rose before mopping up. “By dawn everyone was tied into a close-knit defence and the anti-tank guns were up.” This was the way it was supposed to work!

The enemy struck back with “mortars, moaning minnies, 88-mm, and so forth, but this caused few casualties.” There was no major counterattack and when a squadron of 1st Hussars tanks arrived, Clift was able to send two companies with the tanks to assist the Camerons in Fontenay-le-Marmion. The improvised battlegroup charged into the German flank, sweeping up 350 prisoners of war. The western half of Verrières Ridge was finally in Canadian hands.

East of the Caen-Falaise highway, 51st Highland Div. was responsible for clearing the rest of the high ground, including the village of Tilly-la-Campagne. Initially one battalion, the 2nd Seaforths, were tasked to capture Tilly but the enemy’s 89th Infantry Div. had occupied the well-established defences vacated by 1 SS Panzer Div. and the Scottish battalion was soon caught up in a nightmarish situation similar to one experienced by the North Nova Scotia Highlanders on July 25 (Ferocity And Futility, May/June 2012). Brigade headquarters, as if imitating Canadian decision-making in Operation Spring, ordered the 5th Seaforths to join the attack but their commanding officer refused, insisting “the situation was hopelessly confused and he would wait until daylight and do it properly.”

The next morning, as the 5th Seaforths were teeing up for an assault with full artillery support, a squadron of tanks from the brigade battlegroup that had bypassed Tilly in the night used the cover of the morning mist to strike from the rear, forcing the surviving enemy to surrender.

![COPP3 A jeep kicks up dust as it passes through St. André-sur-Orne, France, August 1944. [PHOTO: KEN BELL, LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA—PA145562]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/COPP3.jpg)

While the Canadian and Scottish infantry battalions fought to control the ridge, the armoured columns led by 2nd Canadian and 33rd British armoured brigades had been dealing with a series of armoured counterattacks. The 12th SS Hitler Youth no longer resembled the division that confronted the Canadians in June, but it was still a significant force. Roughly 1,500 infantry out of 8,000 were left to support battlegroups built around the remaining Panther, Mark IV and Tiger tanks. The artillery and anti-tank guns of 1st SS Panzer Corps, including a Luftwaffe anti-aircraft brigade with dual-purpose 88-mm guns backstopped these units and the reserve regiment of the 89th Div.

Phase II of Totalize was due to begin at 1 p.m. when the B-17 and B-24 bombers of the U.S. Eighth Air Force began bombing the second line of German defences to open the way for 4th Canadian and 1st Polish armoured divisions to advance to Falaise. The 12th SS commander, Kurt Meyer, was later to claim that his decision to send his panzers into action was due to the arrival of a target-marking B-17. Whatever the reason, the decision to allow a famous German tank officer, Capt. Michel Wittmann, to lead a troop of four Tigers directly into a tank trap was simply foolish. A “Firefly,” a 17-pounder-equipped Sherman tank of the Northamptonshire Yeomanry, killed Wittmann and the four Tigers in minutes. A second panzer counterattack was no more successful though they at least escaped the bombs which struck Bretteville-sur-Laize and St. Sylvain “with accuracy and good concentration.”

The senior staff officer of the enemy’s 89th Inf. Div. described the bombing of Aug. 8 in graphic terms: “Wherever artillery and anti-aircraft positions were hit the guns were destroyed or at least hurled out of place by the pressure of the air. All moving parts were clogged up with sand so that the weapons were no longer useable… Roads to the front had for the greater part been rendered useless by the deep bomb craters. This made transportation of munitions and the wounded exceptionally difficult… The psychological effect…was overcome in a relatively short time. Nevertheless the explosions, the near-hits and also the dust and sand…dazed units and individual men, even when they were not actually within the effective radius of the falling bombs.”

The successful attack on the two villages was about all the U.S. 8th Air Force accomplished on Aug. 8. The aircraft attacking targets in the other target area were “badly disorganized” by flak and fewer than 250 of the 474 planes assigned to these targets delivered their bomb loads accurately. Some aircraft bombed close to Caen and inflicted more than 350 casualties on Canadian and Polish troops in the rear areas.

This much-discussed tragedy had no effect on the leading brigades of the armoured divisions which were slowed by traffic congestion and by a renewal of enemy resistance on the ridge. Despite delays, the vanguards of both divisions crossed their start lines shortly after the bombing ended. Everything now depended on two formations fighting their first battle.

Email the writer at: writer@legionmagazine.com

Email a letter to the editor at: letters@legionmagazine.com

Advertisement