An army, it has been noted, marches on its stomach.

Throughout history, invaders and marauders have relied on scavenging and pillaging to feed troops at the far end of very long supply lines.

In 1810, Napoleon said his Grand Armée troops “must feed themselves on war at the expense of the enemy territory.”

French brewer and confectioner Nicolas Appert won a hefty prize from his government in 1810 for his method of preventing spoilage by cooking food sealed inside glass jars—popularly known as canning, after the commercial introduction of cheaper, unbreakable tin containers.

But the method was not perfected by the time Napoleon decided to invade Russia, where in 1812 his scavenging strategy failed against the scorched-earth defence. Retreating Russian forces burned villages and crops behind them, leaving nothing for the half-million invading French troops to eat. Starvation was as great an enemy as the Cossacks and the cold—only an estimated 70,000 French troops survived.

History provides many examples of what happens when troops don’t get proper nutrition. Royal Navy sailors commonly suffered (and died) from scurvy. They gained their nickname—limeys—for the daily dose of citrus juice given to prevent the disease. During the U.S. Civil War, scurvy (caused by vitamin C deficiency) affected nearly 50,000 Union troops, and night blindness (vitamin A deficiency) was common; they were treated, respectively, with fresh vegetables and ox liver.

Military nutritional research and development has been a ringing success for soldiers, sailors and aircrew—and even for civilian consumers, who have benefited from many military nutritional innovations. The United States’ interest in longer-lasting rations in the Second World War paved the way to grocery store shelves for instant coffee, preformed meat products, energy bars, absurdly long shelf life for packaged baked goods and that powdered, finger-staining, orange cheese substance used on some crunchy snacks.

Many countries have their own military nutritional research branches. NATO’s Research and Technology Organization shares results of co-operative research among its members. Its 2010 report found that most members’ rations met minimum nutritional requirements, but some needed supplementation.

Today’s military nutritional concerns focus on optimizing performance, meeting special needs for, say, combat or cold weather, and providing rations and food in garrison that helps build immunity and facilitates recovery from injury and disease.

Taste, smell and appearance are also important. “An inadequate nutritional intake, as a result of under-consumption of the combat ration, may negatively affect a soldier’s physical and cognitive performance,” said the NATO report. Troops must be given time to eat and rations that are easy to eat and sensitive to cultural and religious restrictions.

In the 1980s, the United States established the Committee on Military Nutrition Research to identify factors that influence performance of combat troops in whatever environment they’re called on to work; to identify knowledge gaps and recommend research; and to advise on military feeding standards.

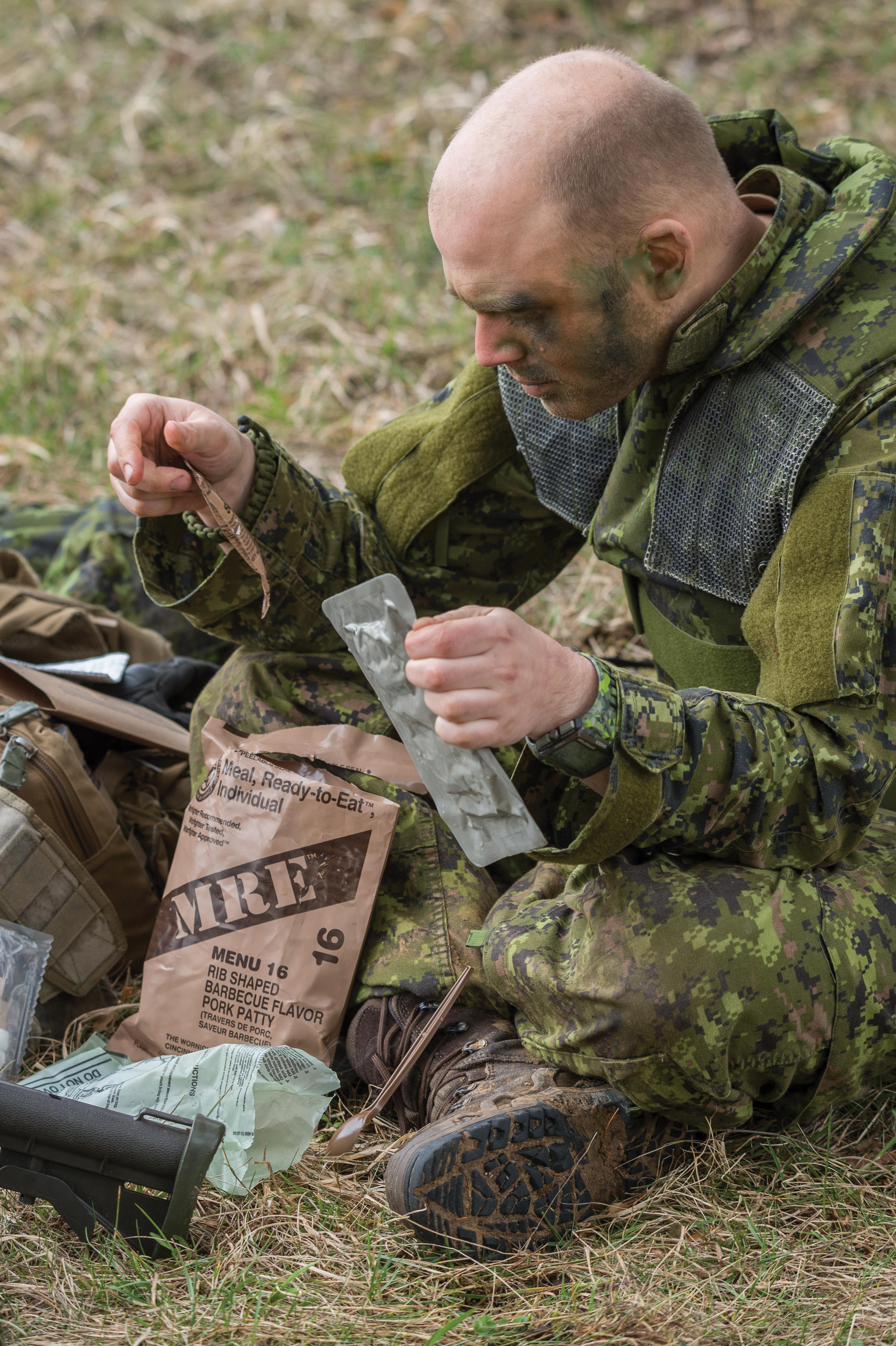

At the same time, the Canadian Armed Forces replaced canned rations with individual meal packs (IMPs). The “boil in the bag” packs can be consumed cold when necessary. (In the field, soldiers have been known to heat IMPs on armoured vehicles’ radiators or exhaust pipes.) Canadian Armed Forces’ field rations reflect Canada Food Guide recommendations and are designed to meet energy requirements of a hard-working soldier.

Three precooked daily meals provide a total of about 3,600 calories. Kosher, halal and vegetarian meals are available. And to prevent boredom, new menu items are introduced and others switched out every three years.

In addition to meals, IMPs can contain powdered coffee, protein and sports drink mixes, energy bars and trail mix, peanut butter, cereal, condiments, candy, chocolate, gum, a spoon and matches.

Research shows soldiers working in the cold need about 1,000 more calories per day, and hydration is a problem in hot environments. Dehydration immediately affects energy production and causes fatigue. Research shows performance drops by five per cent for every one per cent loss of body weight due to dehydration. At a loss of four to five per cent of body weight, performance drops 20 to 30 per cent. Death results when dehydration drops body weight between nine and 12 per cent.

Nutrition is a concern not just on deployment. The 2014 Canadian Armed Forces Health and Lifestyle survey suggests “a notable nutritional knowledge gap among regular force personnel.” While 83.3 per cent of personnel rated their eating habits from good to excellent, 52.2 per cent underestimated Canada’s Food Guide recommendations for fruit and vegetable intake, and only 28.7 per cent ate vegetable and fruit servings more than six times per day.

So the CAF is paying attention to the overall nutrition of personnel, and offers courses on nutrition and weight control. Nutrition courses provide information about balancing activity and energy intake, essential nutrients to reduce health risks, and how to make wise food and drink choices while serving and off-duty.

“Inadequate nutrition is most often due to inadequate planning, catering or supply, and to inadequate training or indoctrination,” noted R.M. Kark of the University of Illinois Medical School in his paper “Studies on Troops in the Field” for the 1952 report Nutrition Under Climatic Stress sponsored by the U.S. Army Quartermaster Corps. “Maintaining good nutrition is like maintaining freedom of speech or democracy. You need eternal vigilance to make it work.”

Advertisement