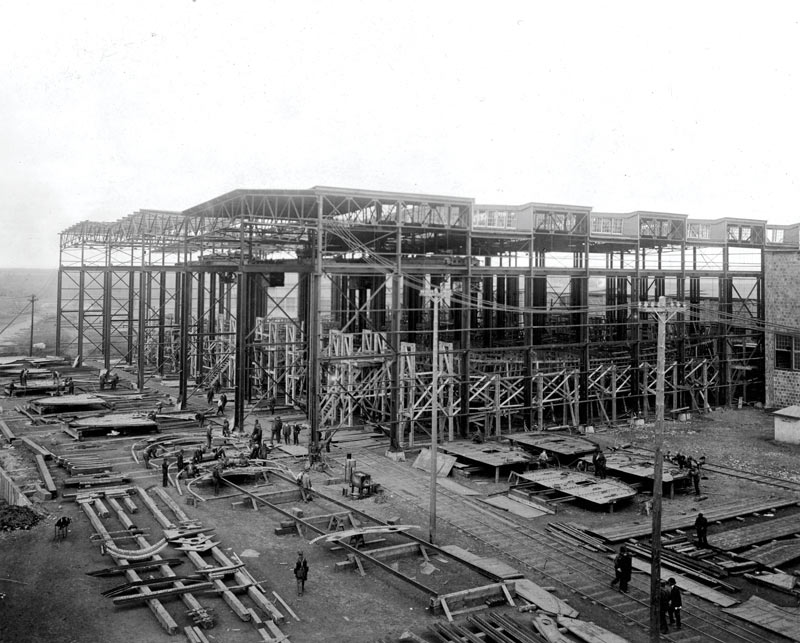

French minesweepers under construction in Fort William, Ont., in 1918 (present-day Thunder Bay). [City of Thunder Bay Archives]

The wrecks of two First World War-era French minesweepers lie somewhere on the bottom of Lake Superior, along with the 78 men who were aboard them. For more than a century, they’ve kept the secret of the greatest marine disaster on the world’s largest freshwater lake.

Here’s what’s known: three new French minesweepers sailed out of the twin cities of Port Arthur and Fort William (now Thunder Bay, Ont.) a couple of weeks after the 1918 Armistice, and only one was seen again. Why were French navy vessels challenging Lake Superior’s notorious gales of November?

By the third year of the war, the French were so desperate for shipbuilders that they turned to yards on the Great Lakes to build a dozen minesweepers. First, they tried Wisconsin’s Manitowoc Shipbuilding Company on Lake Michigan, north of Chicago. It was working at capacity and had to turn down the contract offer. In February 1918, executives of the nine-year-old Canadian Car and Foundry Company in Fort William, Ont.—known as Can-Car by locals—said they could do the job, if Manitowoc engineers helped.

France was to pay Can-Car, which normally built railway cars, $2.5 million for all 12 minesweepers.

In June 1918, as the war began to turn in favour of the Allies after the Germans’ last major offensive sputtered out,

Can-Car workers laid the keel of Naravin, the namesake of the type. The ships were roughed out in Can-Car’s factory and moved on rail cars to the Kaministiquia River, about 500 metres away, to be completed.

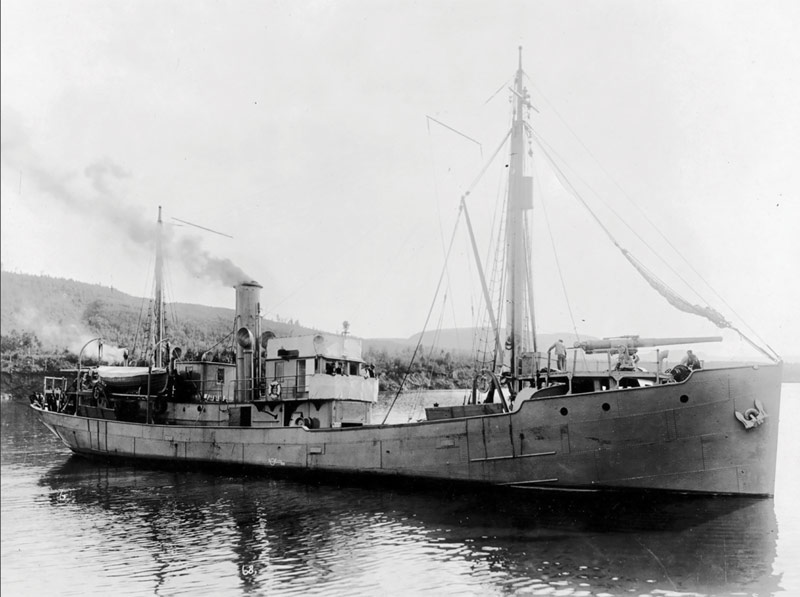

The minesweepers looked like a cross between a navy patrol boat and a fishing trawler, with a single funnel and masts fore and aft. Forty-four metres long and six metres wide, each vessel was divided into four watertight compartments. Powered by coal-fired boilers turning twin screws, they could make 12 knots.

A finished French warship sets out on Lake Superior in November 1918. [City of Thunder Bay Archives]

Each ship was armed with 4-inch guns in the bow and stern. The artillery had a range of about 20 kilometres.

As the minesweepers were being built, the German army was collapsing. However, planning for the project started before the war showed any sign of ending—or that the Allies would be the winners. Still, it seems the French did give some thought to the minesweepers’ long-term use. It wasn’t a coincidence that they looked like big fishing trawlers. Crew members talked about their “fish holds,” suggesting the vessels would eventually be sold off as war surplus to deep-sea fishermen.

Four French officers supervised the pro-ject. French marines arrived in Fort William in September to outfit and arm the warships. One of their officers, Lieutenant Edmond Jean Marie Raoult, died in a wave of Spanish flu that hit the city that fall.

Even Can-Car executives later admitted the minesweepers were built in a hurry, without frills, but they denied the ships were so badly made that they couldn’t handle the Great Lakes.

Six of the Navarin-class vessels were ready to sail by November 1918. By then, however, the war was over. Members of the French naval team probably just wanted to get home. But the ships were still needed to clear the many thousands of naval mines laid by all the belligerents in the Atlantic Ocean, and once winter set in, they and their crews would be stuck in northern Ontario until at least April 1919.

Because the ships were completed late in the year, French officers had trouble finding experienced local captains to guide them through the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River en route to the Atlantic. Most Great Lakes’ sailors were back in their hometowns by that time, and Ontario was in the grip of the Spanish flu pandemic. Still, the return pushed ahead, with Navarin leading the first contingent down the lakes in early November.

By the third year of the war, the French were so desperate for shipbuilders that they turned to yards on the Great Lakes to build a dozen minesweepers.

First Lieutenant Marcel Adrien Jean Leclerc commanded one of the last groups of French minesweepers to depart Fort William, Ont. [lakesuperior.com]

On the 23rd, well past the end of the commercial shipping season, the last group of three minesweepers steamed out of Fort William together. Inkerman was under the command of Captain François Mezou with Great Lakes’ Captain R. Wilson as his pilot. First Lieutenant Marcel Adrien Jean Leclerc skippered Sebastopol and was overall commander. Cerisoles had Captain Étienne Deude at the helm and Great Lakes’ skipper W.J. Murphy as pilot. Along with these officers, there were 74 French sailors and marines on Inkerman and Cerisoles.

The ships were built at Canadian Car and Foundry Company’s shipyards. [City of Thunder Bay Archives]

The fall gales were especially fierce in 1918. Making matters worse, the wind that day was blowing hard from the southwest, across the long western arm of Lake Superior that extends to Duluth, Minn. That meant the ships were buffeted along their sides as they sailed toward Sault Ste. Marie, Ont. If there was trouble, there would be little hope of rescue for the crews, especially since the French ships used a radio frequency that no one else on the Great Lakes monitored.

Most of the voyage happened at night. There are conflicting stories about the departure time of the little fleet. It left Fort William at noon or around 4 p.m. Either way, the captains and pilots had only a few hours of daylight. At that time of year, the sun sets at about 5 p.m. and rises at 8 a.m. And snow squalls swept across the expedition.

No matter when they departed, the ships were in complete darkness when they sailed out of the lee of the islands off the north shore and headed into open water—what sailors called the graveyard of the Great Lakes. Once out of shelter, Inkerman, Sebastopol and Cerisoles encountered 80 km/h winds, nine-metre waves and snow squalls.

By 6:15 p.m., Leclerc on Sebastopol was considering turning back even though he was still sheltered by Isle Royale. Instead, he pressed on into the open lake and made for the south shore to shelter in the lee of the Keweenaw peninsula. He also had the choice of running back toward the north shore and taking shelter at the Canadian Pacific Railway coal docks at Jackfish, Ont., 200 kilometres east of Fort William. But the north shore was dangerous, with most of its small harbours unlit and their approaches peppered with rocks and islands.

French minesweeper Naravin is christened in Fort William, Ont., in July 1918. [City of Thunder Bay Archives]

Inkerman and Cerisoles overtook Sebastopol in the early evening. Still, all the French sailors were in for a night of terror. Exactly what happened on the lead ships as they were pounded by waves the size of houses and lashed by freezing spray, will likely never be known. But, some of the crew of Sebastopol later described the panic on their vessel.

French sailor Marius Mallor later wrote from Port Stanley, Ont., on Lake Erie: “Here I am after leaving Port Arthur, but you can believe me that I would have preferred to have remained there, because on the first night of our voyage, our boat nearly sank, and we had to get out the life boats and put on lifebelts but that is all in a sailor’s life. Three minutes afterwards the boat almost sank with all on board—and it was nearly ‘goodbye’ to anyone hearing from us again…. You can believe me, I will always remember that day. I can tell you that I had already given myself up to God.”

Mallor had good reason to be afraid. The scuppers couldn’t keep up with the cold water piling onto Sebastopol’s deck. It poured into the hold, flooding part of the engine room and nearly putting out the coal fires in the boilers. Without power, Sebastopol would have had no chance against the wind and waves.

Leclerc wasn’t on the bridge. The French commander had gone to bed while the ships crossed the worst part of the lake and was trying to sleep when Sebastopol fell into a trough between two waves. He testified a month later that “the ship came to the left across the wave at an angle, reeled over and made a spoon under the wind. A second wave covered us on the starboard side, a fourth of the personnel on the deck stayed motionless and overwhelmed, the non-active men hastily left the sailors quarters and frantically got the life belts.”

Leclerc had learned through experience that while the Great Lakes might be inland seas, they can’t be sailed the same way. The lakes’ waves are much closer together and arrive more quickly than waves on the ocean. If a ship is caught in the narrow trough between big waves, a helmsman has little time to get the bow pointed back into the waves. Trapped in a trough, the ship can’t be steered and is simply tossed and flooded by the water.

As for Sebastopol’s terrified crew, the most their lifebelts could do was make their bodies easier to find. By late November, Lake Superior is barely above freezing.

Leclerc was able to turn the ship into the waves and “restore order.” The near loss of Sebastopol was the fault of his Canadian captain, according to the French officer.

The French vessels had 4-inch guns in the bow and stern. [City of Thunder Bay Archives]

For much of the night, Leclerc had sporadic radio contact with Inkerman and Cerisoles. By the time they got within 50 kilometres of Manitou Island, off the northeast tip of Michigan’s Keweenaw peninsula, all three ships were taking in water. The storm kept building until midnight, when Leclerc caught sight of the lighthouses at Copper Harbor and Manitou Island.

At the crack of dawn the next morning, Leclerc dropped anchor in Bete Grise Bay, Mich. He sent messages in the French naval code to Inkerman and Cerisoles, but they weren’t answered. (Leclerc later testified the radios on all three ships were substandard and only worked intermittently, so he wasn’t worried at the time.) Still, he expected to see the other two ships sail through the snow squalls into calm water nearby. When they didn’t appear, he convinced himself they were heading to Sault Ste. Marie, Ont.

The local captains were sure Inkerman and Cerisoles were lost and wanted Leclerc to radio to the Canadian and U.S. coast guards for help. Leclerc refused, contemptuous of the Great Lakes’ skippers even though they were right.

“Their silence in response to my wireless messages seemed normal to me, given my instructions,” said Leclerc. “I did not therefore come to a stop at the timid suggestions of my pilots who seemed uneasy about their fate, indeed I had never feared for my ship when I was in control of handling it.”

Yet it’s clear from his own testimony that he never had the helm until Sebastopol was close to foundering.

Instead of searching for the other vessels under his command, Leclerc headed east along the Michigan shore to Sault Ste. Marie, Ont., through snow squalls. Sebastopol cleared the locks there without Leclerc raising the alarm about Inkerman and Cerisoles. Another snowstorm hit Sebastopol on Lake Huron, and Leclerc had to run for shelter again. When Sebastopol reached Detroit on Nov. 28, he finally radioed the French Embassy in Washington that something might be amiss. Then he kept going.

Leclerc’s weather troubles, however, weren’t over. He had to find shelter on lakes Erie and Ontario and repair damage to his ship. Still, he ordered his vessel to hurry to Montreal, then to the Gulf of St. Lawrence so he could get Sebastopol into the open ocean before the St. Lawrence River froze.

Leclerc handed Sebastopol over to a subordinate on Dec. 6. Two days later, he was back on Lake Superior in a tugboat, searching for the missing ships in Whitefish Bay northwest of Sault Ste. Marie. They checked the Canadian shore up to Cape Gargantua, then sailed to Michipicoten Harbour before returning to the Sault in mid-December.

As Leclerc started his search, news of the possible loss of the ships arrived in Fort William. A vessel agent, J.W. Wolwin, received a telegram from the U.S. Hydrographic Office in Duluth asking whether the minesweepers had turned back to their departure point. Within hours, the probable loss of Inkerman and Cerisoles was reported to the city’s newspapers and a separate search began.

Still, city officials, including Fort William mayor Harry (Henry) Murphy, hinted that the two vessels may still have been sailing somewhere on the Great Lakes, under a shroud of censorship and official secrecy. Days before the disappearance was reported to the press, Murphy had been told Inkerman and Cerisoles hadn’t arrived at Sault Ste. Marie. Instead of initiating a search, the mayor and other city officials sat on the news and waited.

During the next few days, rumours swept Fort William and Port Arthur that the ships could have secretly passed the locks in Sault Ste. Marie without being registered because they were foreign naval vessels. Then there were reports that the two missing ships had been seen together in Whitefish Bay by the crew of the steamer Osler.

If anyone had survived the wrecks of Inkerman and Cerisoles, the official delays and the weather worked against them. It was winter and the days were short and the nights long. Tugboats searched the shoreline and islands of Superior’s north shore for the minesweepers, hoping they had taken shelter from the storm or had run aground. The tugs were taking a risk themselves in the big waves and the snow squalls.

“I did not therefore come to a stop at the timid suggestions of my pilots who seemed uneasy about their fate, indeed I had never feared for my ship.”

Experienced sailors said the only hope for the French ships was if they had been beached in some isolated place, which then, and now, describes most of Superior’s coast. Coves and natural harbours along both sides of the lake had been used by ships in trouble for years. But, they had also been the scene of some of the worst shipwrecks. And on the Canadian side, you could count the lit, inhabited ports on one hand.

People in Fort William and Port Arthur were curious about the missing ships, but the rest of the country wasn’t. The loss of the two French warships and all those sailors—the greatest loss of life in a Lake Superior marine disaster—barely made the papers at the time. By the following spring, when it was safe to resume the hunt for Inkerman and Cerisoles, no one in France, Canada or the U.S. cared enough to even bother to search for wreckage.

Instead, people involved in the construction project and the French naval team tried to avoid blame. Canadian authorities didn’t bother with any kind of investigation or inquiry. In fact, the only official government scrap of paper on the disaster in Library and Archives Canada says the vessels were lost on Lake Ontario.

On Christmas Eve 1918, the naval attaché of the French Embassy in Washington chaired a hearing in New York. Leclerc was the main witness. He tried to blame the Great Lakes’ captains who, he claimed, were afraid to sail out of sight of land, unable to predict weather and useful only “in rivers, canals.” He also accused Can-Car of building ships that were unstable in rough water.

In fact, Leclerc may have made his own ships top heavy: he had loaded the last three minesweepers differently than the nine built and sailed earlier. Leclerc had sent the ammunition earmarked for Inkerman, Sebastopol and Cerisoles ahead on an previous fleet, replacing it with some 30 tonnes of coal spread out on the bottom of the hold.

For his part, the local on Sebastopol said its stability seemed “ordinary.” Meanwhile, an inspector for Lloyds, which had insured the ships while they were outside the war zone, said he had watched the Can-Car workers build the ships, and they had done a good job.

“The French minesweepers built at the Canadian Car and Foundry Company’s shipyards were structurally strong and seaworthy.”

“The French minesweepers built at the Canadian Car and Foundry Company’s shipyards were structurally strong and seaworthy, and as perfect a type of boat that I have ever inspected,” Lloyds’ Peter Corkindale told a reporter.

“As well as myself, there were four inspectors from the French commission present while those boats were building. Lt. Garreau was one of them, and he will back up my statement that the minesweepers built at the car works were of the most seaworthy type and perfectly strong…. Some of the best boats ever built have been sunk in storms, and in this case it would only be fair for people to wait for the facts before rushing out with injurious rumours which are not backed by anybody in a position to know what they are talking about.”

(The 10 surviving Navarin-class ships were sold off in 1920, and one was still sailing 55 years later.)

People living along Lake Superior tried to solve the mystery. It’s an exaggeration that the lake never gives up its dead, but it does so unwillingly. The lake is cold and deep. Bodies don’t decompose quickly in the frigid water. And if a body does float, either because of decomposition or it’s in a life jacket, it’s likely no one will find it in the huge lake or along the thousands of kilometres of coastline.

A few years after the disaster, Charles Davieaux, the lighthouse keeper on Michipicoten Island, found a body washed up on the beach. He buried it without the kind of official inquiry and forensic testing we have today, so no one knows whether it came from the two French ships. A skeleton found years later near the little fishing village of Coldwell, on the north shore of Lake Superior, was buried in an unmarked grave.

Supposedly, bits of wreckage from the two ships were found and early in the December 1918 search, Cerisoles’ lifeboat was discovered near Grand Marais, Minn.

Better technology has made it easier to find Great Lakes’ shipwrecks and solve the inland seas’ mysteries. Still, Inkerman and Cerisoles elude searchers, who today are working harder to find the vessels than anyone did in the months after they were lost. Scientific expeditions searched for the minesweepers in 2009, 2015 and 2023.

During that last mission, a team working for the Expedition Unknown television series didn’t find Inkerman or Cerisoles, but they did stumble on the perfectly preserved wreck of the tugboat Satellite, lost in 1879.

Michigan-based shipwreck historian Tom Farnquist believes the vessels are close together northwest of the Keweenaw peninsula, but he hasn’t been able to find them.

“This is the Holy Grail of Lake Superior, to find two 155-foot brand spanking new minesweepers with 4-inch guns fore and aft,” said Farnquist. “One might have got into trouble and the other went to help it and was swamped when it turned its side into the wind. If we’re lucky, they’ll be close together.”

Wherever Inkerman and Cerisoles are, they still belong to the French navy, and the wrecks are war graves.

Naravin floats in Lake Superior near Fort William, Ont., in Sept. 1918. [City of Thunder Bay Archives]

Advertisement