James Arnal’s uniform, draped with a shawl that would have been worn in visits with village elders. [Legion House Museum]

Uniforms, equipment and explosives are

reminders of Canada’s involvement in Southwest Asia

Though fresh in memory, the war in Afghanistan has entered the annals of national history. Aside from personal mementoes brought home by military and civilian personnel, museums have begun building their collections of artifacts.

Bruce Tascona, director of Legion House Museum in Winnipeg, carefully lays out an artifact from the war in Afghanistan, an IED —improvised explosive device—confiscated from a captured terrorist.

“We were using the latest in technology, smart bombs and the like, and facing an enemy that made weapons from stuff you could get at any hardware store,” said Tascona.

Troops were often sent flags signed by grateful Canadians. [Legion House Museum]

Explosives and shrapnel—ball bearings, nails and screws, tin cans cut into bits—would have been packed around this detonator, two rough-cut pieces of pressboard, a pair of springs, some wires, a battery. A soldier’s weight would compress the springs, completing an electrical circuit to the detonator, blowing up the explosives (and the person who stepped on it) and peppering everyone nearby with deadly shrapnel. IEDs accounted for nearly two-thirds of Canada’s 158 military deaths in Afghanistan and many, many wounds.

A fragment of a Taliban rocket. [Legion House Museum]

It has been over 15 years since Canada joined the international campaign against terrorism in Southwest Asia and three years since the Canadian flag was lowered in Afghanistan in March 2014. More than 40,000 Canadian military personnel were involved in the war. Canadian ships joined the international fleet operating in the Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean in October 2001. The commandos of Joint Task Force 2 arrived in Afghanistan two months later, followed by infantry in January 2002. Air Command provided transport and patrol aircraft throughout those tumultuous years.

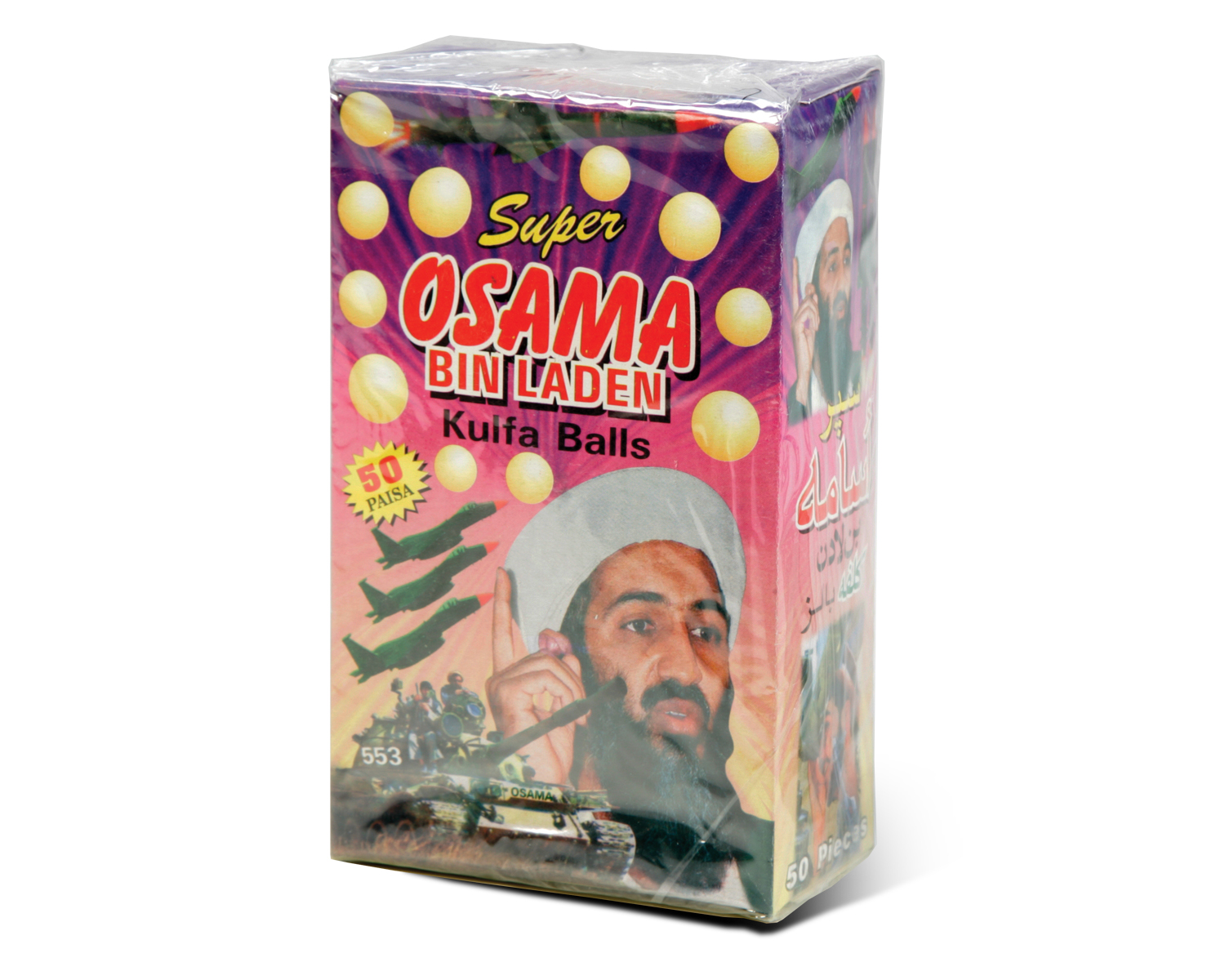

Packets of candy sold in local shops were popular among troops. [Legion House Museum]

“We were using the latest

in technology, smart bombs and the like,

and facing an enemy that made weapons

from stuff you could get at any hardware store,”

– Bruce Tascona

The defence department devised Operation Keepsake to bring home and preserve artifacts documenting every aspect of military life in Afghanistan. Artifacts include material used in the working lives of troops (equipment, captured insurgents’ weapons, field rations, uniform kit, a motorcycle captured from a would-be suicide bomber, IEDs, both whole and in fragments) and their off-duty lives (unit plaques, photos and artwork, the scoreboard from a ball hockey rink, a Tim Hortons sign—even a pair of carved totem poles). The memorial cairn at Camp Mirage and the Kandahar Memorial were also carefully dismantled and returned to Canada.

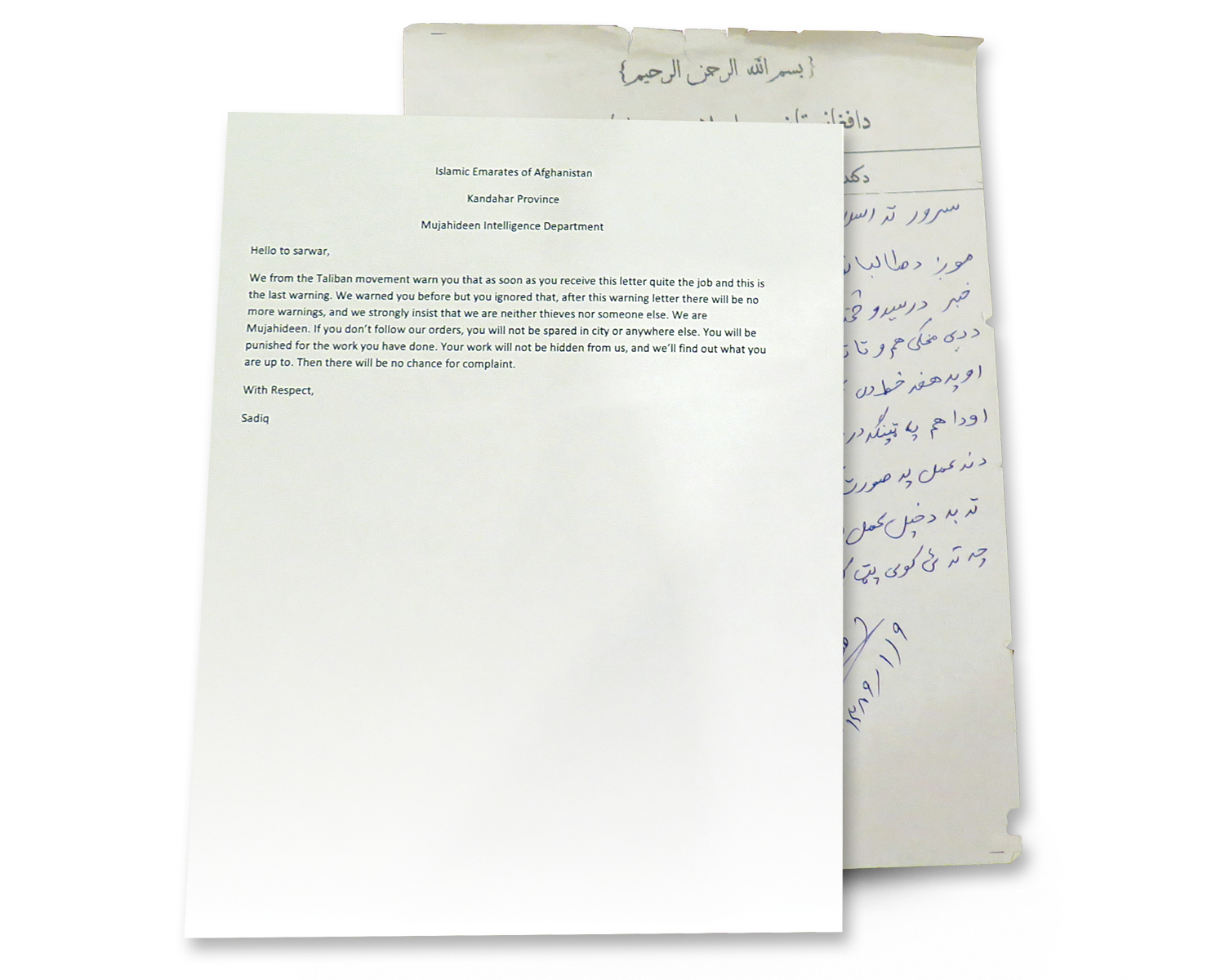

The Taliban nailed letters to villagers’ doors (translated here), warning them not to co-operate with Canadian troops. [Legion House Museum]

Some artifacts were distributed to museums across the country, including Winnipeg’s Legion House Museum. But veterans and civilians have donated the largest part of the museum’s collection.

In its Afghanistan display, just inside the entrance to the Legion’s Norwood-St. Boniface Branch (where the museum is located), is the uniform of James Arnal, killed by a roadside bomb in 2008, donated by his mother, and an Afghan interpreter’s clothing, brought back by a soldier.

A (defused) improvised explosive device seized from a would-be suicide bomber alongside shards of plastic from a container housing, perhaps concealing, a bomb that did explode. [Legion House Museum]

A soldier deployed to Afghanistan in 2012 brought back and donated maps used on patrol, featuring landmarks renamed as sports teams to confound any enemy listening in. He also brought back posters that had been tacked onto Afghan citizens’ doors by terrorists, warning of dire consequences of working with foreign troops or taking jobs in support of the government. Give up the work, they warn, or “you will be punished for the work you have done…you will not be spared in the city or anywhere else.”

“Our soldiers were there fighting terrorists, but they were also fighting for the hearts and minds of the people,”said Tascona. “Fighting to give them a better life.”

Advertisement