When the Houston-based Lady Washington chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution set out to put headstones on the graves of unrecognized veterans, they didn’t expect to find a couple of lost Canadians. But that’s just what they did at an area cemetery known as Little Arlington, where the unmarked burial plots of two Canadian veterans of the First World War turned up among at least 70 recorded but unmarked graves.

They are Lawrence Leslie Van Every of Galt, Ont., and James Edward Morton of Victoria. “I couldn’t believe they were essentially forgotten,” said Christine Herron, a local society member who, along with her mother Pat, a retired U.S. army colonel, spearheaded the Texas project.

“We needed to make sure that they were properly honoured.”

The mother-daughter team researched each American buried without recognition of their wartime service. U.S. Veterans Affairs picked up the tab for the American headstones, while the society and the cemetery split the installation costs.

Van Every’s history landed in the lap of Katherine Shelley, an American-born immigrant to Canada descended from four Mayflower passengers and seven colonial soldiers of the 1775-1783 American Revolutionary War. She now lives in Toronto and is the recording secretary for the society’s Upper Canada chapter.

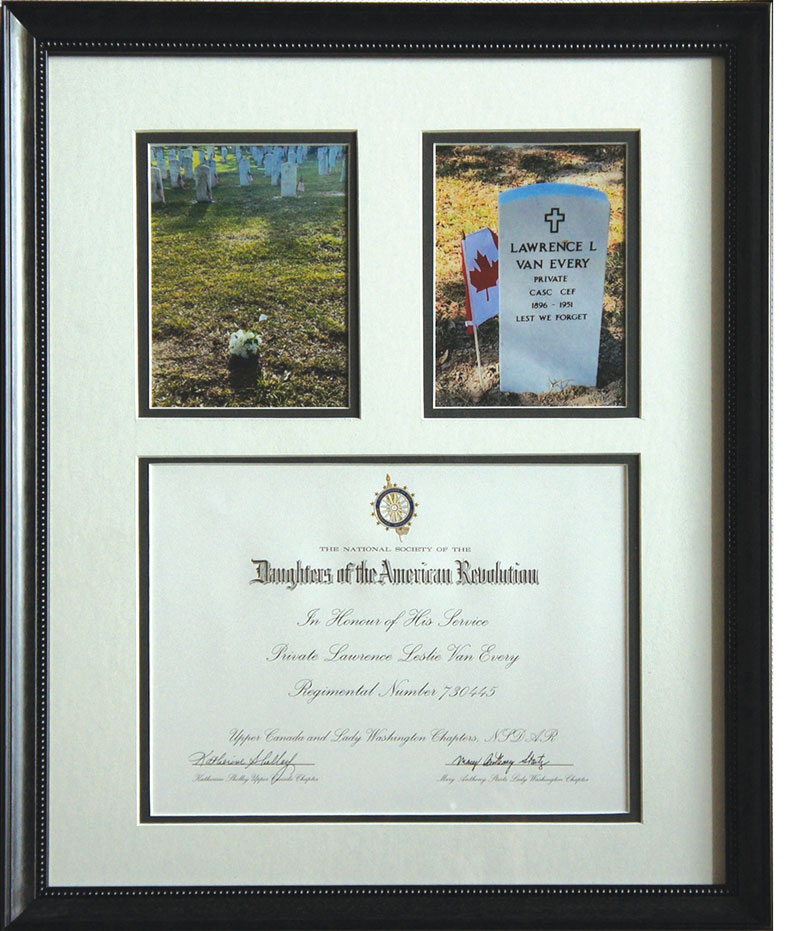

“I got to know these guys,” said Shelley, whose grandfather fought in the First World War and father in the Second World War. While Shelley immersed herself in the family history, Pat Herron secured headstones for Van Every and Morton through Veterans Affairs Canada.

They were installed just ahead of Remembrance Day 2020 and a year later, on Nov. 6, 2021, Shelley delivered a talk and made some presentations to The Royal Canadian Legion branch in Galt.

Van Every was one of six in his family who enlisted for wartime service, including two brothers and three uncles, two of whom died during the war, one in combat. Van Every was 19 when he walked into the recruiting office in Galt, listing his address as 78 Ainslie Street North, 800 metres down the road from the present-day Legion branch where Shelley spoke.

Private Van Every, a wood craftsman, or turner, ended up with a reserve battalion, was assigned to the Canadian Army Service Corps (CASC), caught a minor head wound in October 1916 and was shot in the right hip in April 1917, possibly at Vimy Ridge.

Besides his wounds, he was plagued by a litany of health problems not uncommon among First World War soldiers. His military service, however, was rather uncommon. In June 1917, he disappeared for more than eight weeks. To make matters worse, he’d lost his regimental kit. He was convicted of being absent without leave and having “deficiencies in his kit and equipment.” It cost him 23 days’ pay and allowances. But the colourful Van Every wasn’t done. He deserted in January 1918 and spent 46 days on the lam.

While 25 Canadian deserters got a firing squad during the First World War, a March 1918 court martial sentenced Van Every to two years in one of Britain’s largest prisons.

The catalyst to his misdeeds appears to have been love. In June 1919, while in detention at His Majesty’s Prison Wandsworth in southwest London, the War Office granted him permission to marry, an extraordinary concession to an imprisoned two-time deserter. Not only did he avoid death, his sentence was “remitted,” or suspended, on July 23, 1919, and he was shipped home on Sept. 3.

Upon his return to Canada, Van Every and his English bride emigrated to Detroit. He worked railroads across America, at one point losing a job in Washington. In 1929, the couple had a son, Laurence, who died childless in 2002.

The details of how Van Every ended up in Texas are lost to time, but that’s where he died of congestive heart failure in 1951, age 55.

Through her research, Shelley found the Van Every family left the Netherlands for the American colonies in 1653. During the Revolution, McGregory Van Every was persecuted for his staunch United Empire Loyalist views. His sons, active members of Butler’s Rangers—a British unit in the Niagara region—received generous land grants in Upper Canada’s Niagara Peninsula and Wentworth County after the war.

Morton, the other Canadian buried without a marker in the Woodlawn Cemetery, joined up at age 38. He was a house painter living in St. Louis, Mo., with no family and served with the 9th Battalion, Canadian Railway Troops, and later the CASC.

He was discharged in Montreal on March 12, 1919, and died in 1936.

Besides her presentation, Shelley made a donation to Galt’s poppy fund on behalf of the Daughters of the American Revolution and presented the branch with memorial plaques commemorating the six local Van Everys who served.

The society was founded in 1890 “to preserve the memory and spirit of those who contributed to securing American independence.” Women 18 or older with proven lineal descent from “a patriot of the American Revolution” can join. It has nearly 185,000 members worldwide.

Advertisement