I like to think, as a relatively well-informed Canadian with an interest in history, that I’m at least aware of my country’s major military conflicts. I have read about Canadians’ courageous service in the Great War, the Second World War and Korea. My chest swells with pride around Canada’s peacekeeping missions. Canada’s role in NATO has earned international respect, irrespective of former U.S. president Donald Trump’s jabs.

But I must confess, I knew nothing about the Aroostook War back in 1838-39. That may be because back then, Canada was not yet a sovereign nation. It was known then as British North America. But still, you would have thought I might have heard something about it. I mean it was a “war” after all. Or was it?

After researching the topic, I’ve decided it was simply easier to refer to it as the Aroostook War, rather than as the Aroostook international incident, or the Aroostook border dispute, or perhaps the Aroostook territorial demarcation debate.

None of those names seems to wield the hard-hitting impact of that all-powerful word “war.” So, let’s go with the Aroostook War, shall we? Perhaps it doesn’t matter that nary a shot was fired. Even “skirmish” seems too violent a word to describe it.

Hold on. I know you might be a bit confused about all of this—I know I was—so let me provide some much-needed context within which we can then examine what has become known as the Aroostook War.

During the Napoleonic Wars, Britain had a surging need for timber, particularly for building naval vessels for their fight with France. Unfortunately, a French blockade prevented the Brits from buying timber from their traditional suppliers, the Baltic states. So, England looked westward to its North American colonies.

New Brunswick in general, and its Aroostook Valley in particular, provided seemingly endless white pine forests that yielded perfect masts for British naval vessels. New Brunswick timber exports soared to represent two-thirds of total provincial exports and helped to establish a flourishing lumber industry. This, of course, spawned competition as timber interests in southern Maine and Lower Canada showed up in New Brunswick to snag some of the action.

That all sounds like a market economy the way it ought to work. But—and it’s a very big but—at the time, this particular part of New Brunswick was disputed territory. You see, when the Treaty of Paris in 1783 ended the Revolutionary War between the British and the United States, the border separating the latter and the North American colonies of the former, specifically between New Brunswick and Maine, was never clearly defined and became a source of contention and acrimony for decades.

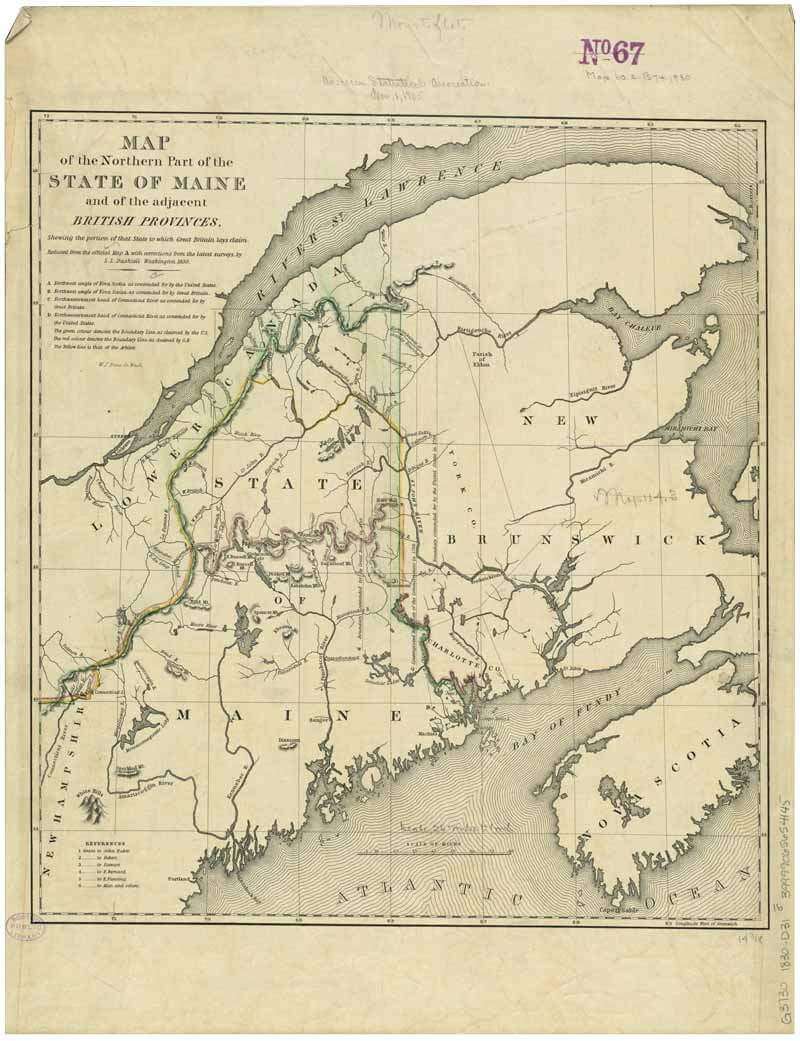

Years after the dispute between New Brunswick and Maine, the Aroostook River region was still a logging hot spot[Library of Congress/2001696194]

In the years that followed the signing of the Treaty of Paris, several official commissions and other attempts at negotiated settlements still left the actual placement of the New Brunswick-Maine border in dispute with prime timber lands claimed by both sides.

Fortunately, the governments of both countries did not consider this little patch of disputed territory—while important symbolically and certainly critical to the locally affected communities—to be worth shedding blood over, so they agreed to continue to try to reach a negotiated compromise.

Many more years were spent by even more commissions in attempts to resolve the matter, if not amicably, at least begrudgingly. From 1816 to 1821, yet another joint British-American commission utterly failed, again, to define a national border to the satisfaction of Maine and New Brunswick. Some 38 years after the Treaty of Paris, the territorial dispute was still unresolved.

Governor Fairfield sent in his state militia, leading to what could only

be termed a “standoff.”

Governor Fairfield sent men to arrest New Brunswickers logging in the disputed territory in early 1839. [Maine State Archives]

This left all those living in the disputed region, including Brits, the French and Americans, increasingly angry. They all began agitating and backing up their respective claims on the land.

Emboldened by Maine’s statehood in 1820, settler John Baker began spoiling for a fight. He undertook various acts of civil disobedience in the contentious territory, defying the British authorities. He even urged the French in the region to reject British rule. Baker’s efforts, or antics depending on your perspective, continued for years.

Finally, on July 4, 1827, Baker unilaterally proclaimed the independence of what he called the Madawaska Republic, recognizing only the authority of the United States. For the Brits, that was a step too far.

American Daniel Webster and Brit Alexander Baring negotiated a treaty that settled the boundary in 1842.[Provincial Archives of New Brunswick/H2-203.202-1830]

They arrested Baker, threw him in jail for eight months and eventually at trial, found him guilty of sedition and conspiracy, sentencing him to an additional two months in jail and fining him 25 pounds. (I know what you’re thinking: don’t you find him guilty first, then imprison him? Well, that’s not the way it went down.)

This seemed to bring the matter to a head, which is just what Baker wanted.

The British and American governments then paid a visit to King William I of the Netherlands and asked him to, once and for all, mediate an end to the dispute and finally define the New Brunswick-Maine border.

The good king decided that the Saint John River was the logical boundary. Both London and Washington were prepared to close the book on this nagging irritant and accept the solution. Regrettably, the citizens of Maine were not. They flatly rejected the proposal and refused to relinquish one square inch of the contested territory.

By 1838, tensions escalated further, and armed conflict seemed inevitable. Newly elected Maine Governor John Fairfield was worried and/or angry about “provincials” (you know, New Brunswickers) illegally logging within what he considered to be Maine’s borders. So, in early 1839 he sent what can only be described as an armed posse, under the leadership of one Rufus McIntire, to the Aroostook Valley to arrest New Brunswick loggers. Here’s where our simmering pot boiled over.

The governing authorities in New Brunswick declared Maine’s actions an invasion and summarily dispatched troops to the region. Before they arrived, New Brunswick loggers—legendary tough guys—had already armed themselves, turned the tables on McIntire and arrested him. He was transported to Woodstock, N.B., for what was euphemistically called an “interview.”

Of course, when Governor Fairfield learned of this, he was none to pleased. Okay, he was apoplectic. He sent in his state militia, leading to what could only be termed a “standoff.”

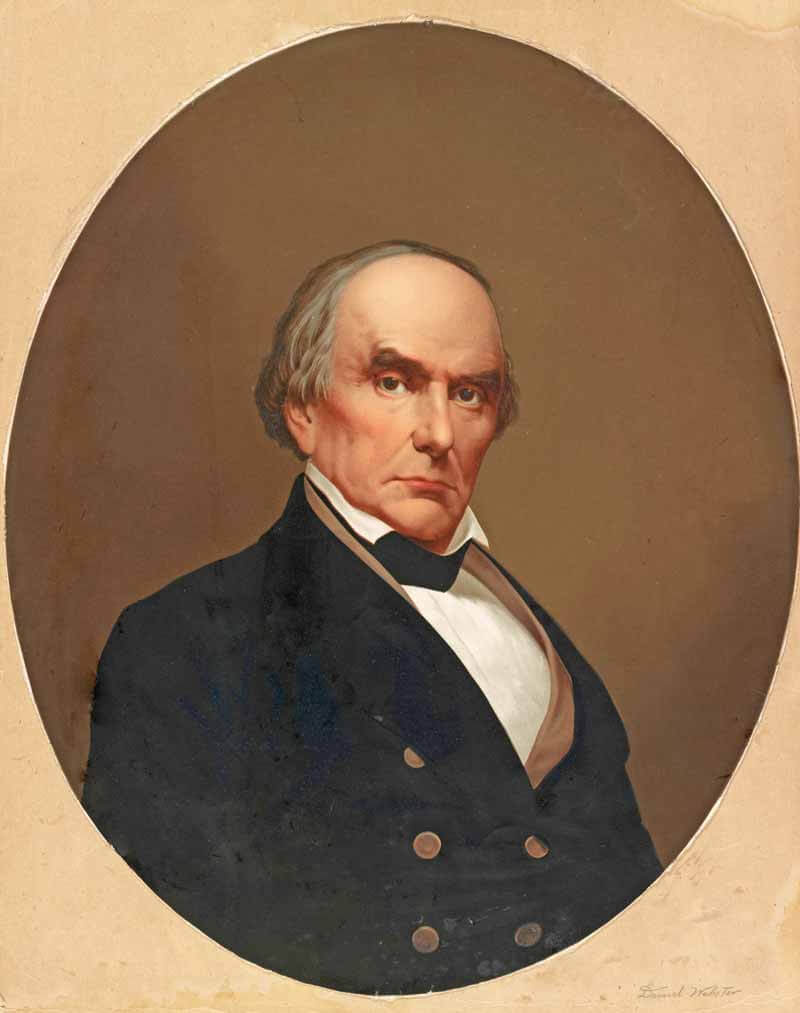

Clearly neither the British nor the American governments believed this minor territorial irritation to be war-worthy considering the mutually profitable trading relationship between the two countries, so—once more unto the breach—a final, final, final negotiated resolution was attempted, yet again, this time through the co-operative efforts of American Daniel Webster and Brit Alexander Baring, 1st Baron Ashburton.

In 1842, their work yielded the Webster-Baron Ashburton Treaty, which at last divvied up the disputed territory between the British and Americans.

American Daniel Webster and Brit Alexander Baring negotiated a treaty that settled the boundary in 1842. [Niday Picture Library/Alamy/DERF3P; George Peter Alexander Healy/New York Historical Society/Wikimedia]

American Daniel Webster and Brit Alexander Baring negotiated a treaty that settled the boundary in 1842. [Niday Picture Library/Alamy/DERF3P; George Peter Alexander Healy/New York Historical Society/Wikimedia]

What an ordeal! It started with the ambiguously worded Paris Treaty of 1783 and was finally resolved in 1842—a 59-year odyssey. It is worth noting that no one died in the so-called Aroostook War. Not one soul. Although, it was reported that an old-fashioned, knock ’em down, drag ’em out donnybrook broke out in an Aroostook Valley tavern.

Apparently, New Brunswick loggers did not react well when a member of the Maine militia raised his glass to toast his home state. It was reported to have been quite a tussle. So, while no shots were fired in anger, some punches were evidently thrown.

There were non-combat casualties, however. We ought to spare a thought for the one soldier commemorated by the Daughters of the American Revolution for losing his life during the Aroostook War. A granite marker was erected alongside Route 2A near Haynesville Woods, Maine, to honour Private Hiram T. Smith and his sacrifice.

No one can say for sure just how Smith died, but my research has provided what one might call informed speculation. (I’m not kidding about this.) The theories that have gained at least some modest credence include freezing to death, being run over by an army supply wagon or being killed by a horse he had gone to feed. An article in a 2003 issue of Wired magazine also mentions the possibility that Smith drowned in a nearby pond, now known as Soldiers Pond.

It was reported that an old-fashioned, knock ’em down,

drag ’em out donnybrook broke out in an Aroostook Valley tavern.

Having researched the Aroostook War for this humble article, I fully understand why so few of us had ever heard of the conflict. And I still can’t really explain how it came to be known as a “war.” Any NHL hockey game presents more violence in 60 minutes of ice time than was seen in the nearly 60-year-long dispute that became known as the Aroostook War. There’s always a winner when the Leafs and the Canadiens play, even if it takes a shootout.

In the Aroostook War, there was no shootout. Rather, it ultimately required the goodwill of Webster and Baring, along with a pencil and map of the Saint John River, to end the longstanding territorial dispute. And to this day, I’m not sure which side won.

Terry Fallis is a bestselling novelist and two-time winner of the Stephen Leacock Medal for Humour.

Advertisement