Able Seaman Don Fraser, a gunner aboard HMS Belfast, received the last of his wartime medals when he was 103. [Kyle Scott/Fraser family]

He is believed to have been among the crew aboard the cruiser HMS Belfast when it took part in the spring 1944 attack on the German battleship Tirpitz. He was a rare example of a sailor who actually set foot on the D-Day beaches, helping to retrieve wounded soldiers. And he was in the convoys that sailed the notorious Murmansk run delivering war materiel from Halifax and New York to Soviet Russia.

Fraser was 90 before he secured the first of his wartime medals.

Fraser survived the gauntlet of cold weather, high seas and German U-boats, yet he was 90 before he secured the first of his wartime medals, and 103 before he pinned the last of them on his chest—just months before he died.

That he did so at all was thanks largely to Kyle Scott, an ex-combat engineer and veteran of multiple Afghanistan tours who has made the acquisition of medals for the deserving few who have earned them his labour of love.

Don Fraser wore his complete set of Second World War medals for the first and only time just months before he died at 103. [Kyle Scott]

Years after that, Scott and a British friend, helicopter pilot Stuart Doyle, collaborated to land Fraser his two campaign medals: the 1939-45 Star and the Arctic Star, which was created in 2012.

Fraser had been a gunner aboard Belfast, to which the Canadian had been seconded. The British ship had fired 6,000 rounds onto the Normandy beaches on June 6, 1944, before he joined a shore party to fetch wounded and bring them back to the ship’s operating room.

Fraser finally had all five of his medals pinned on his chest in May 2017.

“He got to wear all his medals the one time before he passed away,” said Scott. “We put on a ceremony at the extended-care facility where he lived. All of his family were there—great-grandkids, everybody.

“He was incredibly proud. He was right back in that sailor’s uniform standing on the bow of the ship. It was really special.”

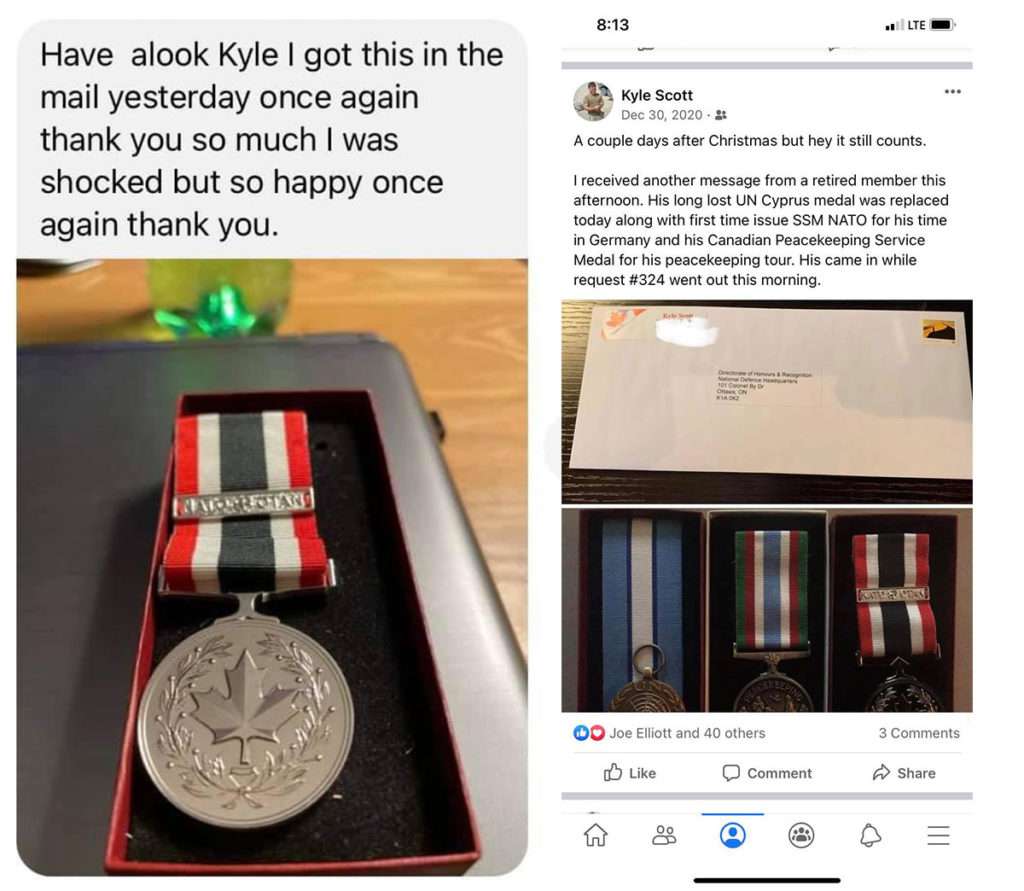

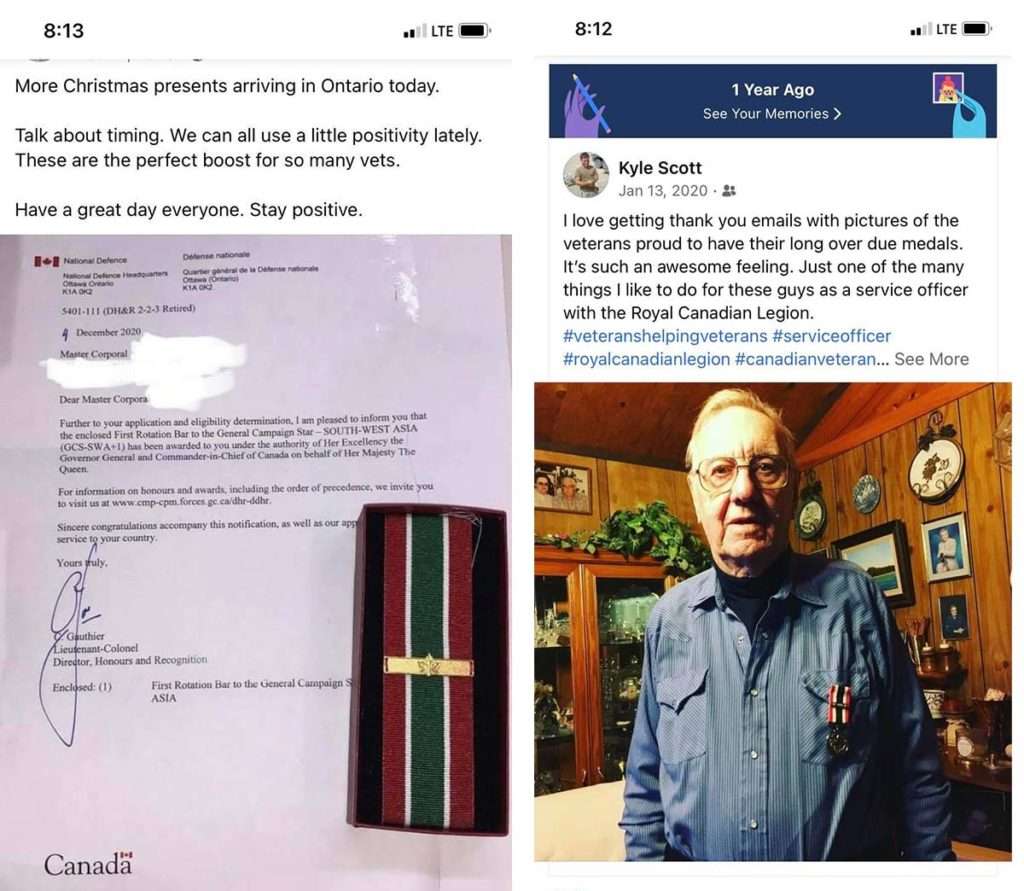

Some of those for whom Scott has acquired medals. [Kyle Scott/Facebook]

Military veterans who never receive the medals they earn are surprisingly common. Some would sooner forget their wartime or military experiences. Some of those suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder and other maladies even throw out or give away the medals they do have.

Scott says many veterans, as recently as Iraq and Afghanistan, shook off head injuries and other wounds and never reported them, passing up on the opportunity to receive wound stripes or the more recent Sacrifice Medal.

Then there are the medals that are lost, stolen or thrown out by bitter spouses in messy divorces. All can be replaced by the Honours and Awards Secretariat at Veterans Affairs Canada or the Directorate of Honours and Recognition at the Department of National Defence, depending on the medal.

Service medals earned during the Second World War were not automatically awarded. Veterans had to apply for them. Many didn’t know they were eligible for medals; others didn’t care.

“No one could know where these men ended up after the war when they finally had the criteria set and all the medals created,” said Scott. “Think of the men that took land grants and moved; others were chasing work; even more were just lost trying to find themselves.”

Some acknowledgements of Scott’s work. [Kyle Scott/Facebook]

Scott later helped a friend acquire a peacekeeping medal.

The passage of time has also been a factor. As veterans grow older, and have children and grandchildren, they learn to deal with their pain and bitterness, they realize their legacy and the significance of all they’ve been through.

Fraser’s case “kinda lit a fire in me,” said Scott, a retired corporal living near Edmonton. “On one hand, I was so proud to have played a part in this and help this World War Two veteran receive his extremely long-overdue recognition.

“But, on the other hand, I felt bad for him. After all, 70 years had gone by and here he had found himself standing among all of his comrades [on Remembrance Day] with nothing on his chest and all of them as proud as could be.

“I thought, there’s got be more out there.”

Raymond DeKelver’s medals (from left): The 1939-1945 Star; The Defence Medal; The Canadian Volunteer Service Medals with Overseas Bar and Dieppe Bar; The 1939-1945 War Medal; The Canadian Peacekeeping Service Medal; The United Nations Emergency Force Medal; and the Canadian Forces Decoration. DeKelver never saw the complete set. [Kyle Scott]

There certainly were. Scott later helped a friend acquire a peacekeeping medal he didn’t know he’d earned (they, and NATO special service medals, are commonly overlooked by many veterans), and things snowballed from there.

Now Scott is the go-to purveyor of medal acquisition services, probably the country’s most well-informed and efficient non-military volunteer to undertake the task of actually searching out veterans, identifying their eligibility and acquiring what they are due.

Some acknowledgements of Scott’s work. (Kyle Scott/Facebook)

“There’s nobody else doing this to the degree that Kyle is doing it,” said New Brunswick’s Gary Campbell, a 42-year militia and regular-army veteran and the Legion’s national medals adviser. “He’s the only one that I’ve run across.

“People do it in dribs and drabs. Like I’ve done a handful over the past 15 years but I don’t go out searching; we intersect. He’s out there basically rooting and digging. He’s got notices out on various regimental associations’ Facebook pages and who knows where else. He’s very proactive. He’s dedicated and he’s hard-working.”

The elder DeKelver was wounded and captured during the disastrous Dieppe Raid.

In 2019, Scott met Aidan DeKelver on a battlefield pilgrimage in France. Standing on the legendary beach at Dieppe, DeKelver told him the incredible story of his father, Raymond Matthew DeKelver who, as an 18-year-old farm boy from Pleasantville, Sask., joined the army in 1940.

The elder DeKelver was wounded and captured during the disastrous Dieppe Raid in 1942—a fact that was not lost to anyone who was there on the pilgrimage that day. DeKelver had an unusual and protracted army career.

He spent two-and-a-half years as a prisoner of war, left the military in April 1946, rejoined in 1948, was posted to Ottawa during the Korean War, left again in 1951, rejoined in 1955, was in the first contingent of the seminal UN emergency force that occupied the embattled Suez in 1956, and retired a lance-corporal in 1966 after an eventful quarter-century in uniform.

DeKelver died in 1989, never having seen all the medals he’d earned.

After returning from the pilgrimage, Aidan sent Scott a photograph of his father’s medals. Scott saw right away that DeKelver had not received his long-service medal (the Canadian Forces’ Decoration) or the Canadian Peacekeeping Service Medal he’d earned on that mission to Egypt.

The latter is the same mission for which Lester Pearson was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize “for his crucial contribution to the deployment of a United Nations Emergency Force in the wake of the Suez Crisis.” It was the birth of peacekeeping.

Scott filled out the paperwork and in a few months Aidan received the medals. Thrilled, DeKelver’s son immediately had the whole set remounted and framed. He keeps them in a safe in his garage.

“I’m pretty proud of them,” said Aidan, who’s taken them to his children’s school to talk about his dad. “I keep them safe.

“Kyle was instrumental. He was fantastic. He’s given years of his life to help all of us.”

Aidan and Scott remain friends.

Aidan wanted to join the army when he was 17.

“My mom had refused to sign the papers and said ‘you’ll have to talk to Dad,’” he recalled. “When I turned 18, he took me out and we went to the Legion. He basically talked me out of joining. He just said, ‘I’ve done enough service for all of us; I don’t want you to see what I’ve seen.’ And that was the end of that.”

Eventually, his dad “got tired of signing me into the Legion to watch hockey, so he got me my own card.” Aidan’s been a member ever since.

He says his father’s service has brought him recognition he never expected, nor asked for.

“I get all these accolades for all this stuff I never did,” he said. “All these engineers on the tour wanted pictures with me with their regimental flags and everything.

“I’m an army brat, through and through. I’m always proud when he gets brought up in conversation.”

Scott comes from a military family, too. Military history is in his blood. He was raised on it and has a passion for it. He suffered post-traumatic stress after his Afghanistan tours. He says helping others, including his fellow Afghanistan veterans, helps him cope. The kudos were coming in even as he was sending along pictures for this column.

“It’s motivation for me to keep finding more and more,” he says.

For more information on Canadian military medals and decorations, go to: www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/help/faq/medals-decorations

Advertisement